“I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest he” — Colonel Thomas Rainsborough (Leveller spokesman), Putney Debates (1647).

In 1829 my great, great, great grandfather Edward Thomas married Elizabeth Dalton in what was described by Hartley Bateson in his Centenary History of Oldham (1949) as a “…temporary shed over the hearse house.” that was used during the re-building of Oldham parish church.

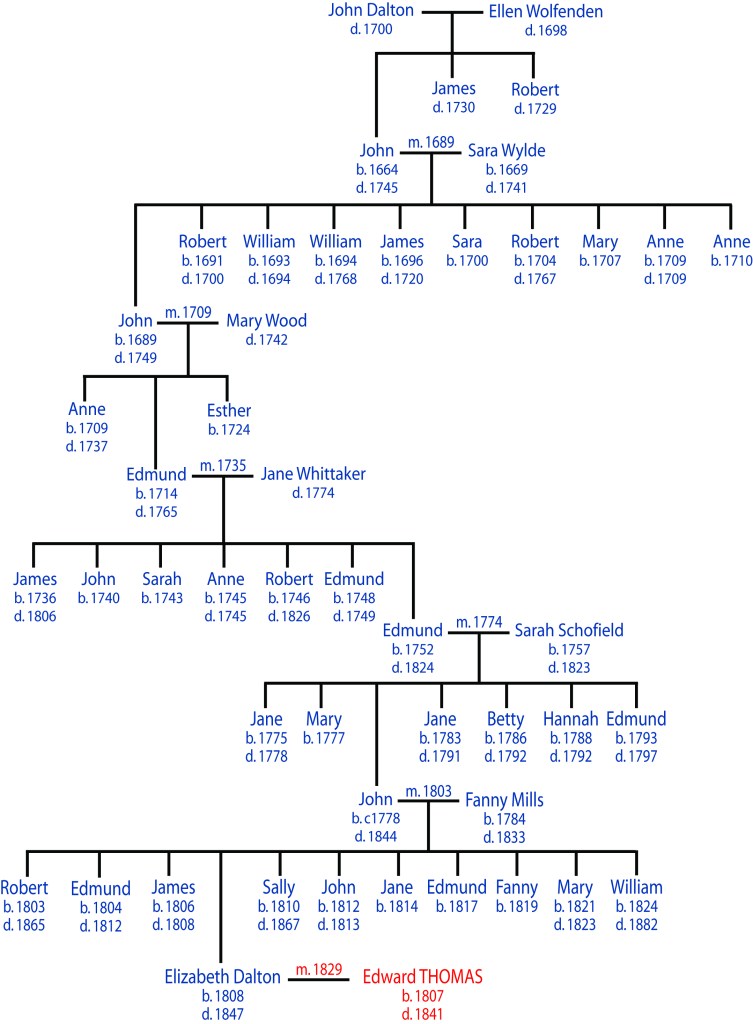

The first record of a Dalton from Oldham church is the christening of one John Dalton on the 3rd April 1664, this boy’s parents were John and Ellen. According to Ellen Slater (1986), John Sr. and Ellen would have two other sons – James (b. 1667) and Robert (b. 1670). Seventeen years later (1681) the records of the Cudworth family, who were lords of the manor of Werneth within Oldham, show the rental of a cottage to a John Dalton, husbandman (see Appendix 1). The indenture of lease also states that this dwelling is already occupied by John Dalton’s mother-in-law, Ellen Wolfenden. In the baptismal record the mother’s name is Ellen, I think it’s reasonable to assume that she was named after her mother (Ellen Wolfenden), and that the renter of the cottage and the father in the baptismal record are one and the same. John rented the cottage, and perhaps a small piece of land by “…paying thereafter yearly to the said Joshua cudworth…rent of three shillings of good and Lawfull money of England at the feast dayes and tymes of pentecost and Saint Martin the Bishopp in winter by even And equall portions And in boones one day shearing yearly in the tyme of harvest with an Able person…”.

The Dalton’s cottage was probably a single-storey, brick or stone structure with a thatched roof and two or three rooms. The illustration on the left, below, shows a weaver’s cottage on the isle of Islay at the end of the 18th century. At this time, 100 years after John Dalton rented his cottage, this home was described as ‘primitive’ by the visitors from London (Banks, J., 1772), so might be similar to the one rented by John Dalton in Oldham. Such an assumption is supported by the image on the right showing the last thatched cottage in Oldham which is similar in structure to the Islay cottage – except for the presence of dormer windows and chimneys. It’s most likely that the Daltons’ cottage was similar to the Islay cottage in that the smoke from an open fire within the cottage would have escaped through a simple hole in the roof. The cottage would have had an earthen floor, the fire being used both for comfort and for cooking. The description of John as a husbandman in the cottage lease suggests that he may have farmed a little land and kept a few animals, chickens and pigs, perhaps. The family may even have shared their home with these animals – part of the cottage possibly being used as a byre to house the animals in winter.

At this time, working men would have worn long stockings, loose woollen breeches and linen shirts covered by a short tunic or jerkin, while women wore long skirts with aprons and bodices over linen shifts. Women would cover their hair with tight-fitting coifs, or wimples, and men wore woollen hats of various styles. Both men and women would have worn leather shoes, and in winter they’d have attempted to stay warm using woollen or sheepskin cloaks and mittens.

The christening in 1664 would have taken place just four years after the restoration of the Monarchy following the return of Charles II from exile in the Netherlands. At this time, Oldham was a village of perhaps 250 households. In 1666 there were 143 households liable to the Hearth Tax (214 hearths; Giles Shaw, Manuscripts). Larger premises had numerous hearths: Chamber Hall had eight (owner: Benjamin Wrigley), Lees Hall had eight (owner: Thomas Kay), Werneth Hall had six (owner: Joshua Cudworth), Bent Hall also had six hearths, and both Horsedge and Hathershaw Halls had four. Walton (1986) estimates that about 40% of households in south-east Lancashire were exempt from the tax, assuming a similar proportion of exemptions in Oldham gives a total of 238 households, and with an average of 4.75 people per household, I estimate the population was about 1130. (For comparison, Aikin gives a total of 433 households in Oldham in 1714, with 906 households in the combined townships of Oldham, Crompton, Chadderton and Royton).

The major industries would have been sheep farming and the weaving of woollen or fustian (coarse cotton) cloths. Indeed, in the Journal of the Dalton Genealogical Society, John Jr. (b. 1664) is described as a weaver of Fogg lane (later King Street). Even at such early dates, long before the Industrial Revolution, John Jr.’s occupation of weaver represents one of the predominant trades in the town, and gives a pointer to the changes to come in the future. Likewise, his brother James’ job as a coal miner would play a prominent role in the development of Oldham to become the greatest centre of cotton spinning the world has ever known (e.g., see “The Oldham Joneses…” under Miscellany). Nevertheless, in the late 17th century there were still few clues as to the enormous changes that would occur in the town in the next two hundred years.

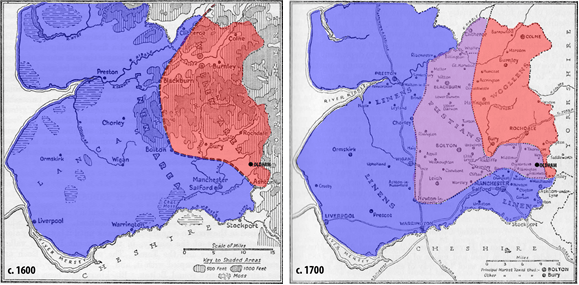

The move of John Jr. into weaving may have meant that one of the rooms in the cottage was given over to housing his loom (the loomshop), with the family either extending the cottage or, more likely, dispensing with the byre. Loomshops used for cotton cloth manufacture were generally situated at the rear of the premises away from the entrance to avoid draughts and maintain the humid atmosphere; however, it’s not clear whether John would have been a weaver of wool or cotton cloth. Oldham would later become a powerhouse in the spinning of cotton, however in the late 16th and early 17th centuries the weaving of woollen cloth was probably more common (see c.1600 map, below).

Growth of the Cotton industry in Lancashire

The wool industry in the north of England was concentrated in Yorkshire; however the proximity of Oldham to the county border, and the unsuitability of land in the town to arable crops, would have favoured the farming of sheep and development of woollen cloth weaving. Note also the stipulation in John Sr.’s lease that he had to spend one day a year shearing the lord of the manor’s sheep. Still, by the middle to late 1500s imported cotton fabrics from the continent had begun to be very fashionable in Britain, and the roots of a domestic cotton manufacturing industry were beginning to grow. In East Anglia and Yorkshire these roots withered rather quickly, mainly because of the strength of the local woollen industries and the lack of raw cotton (at this time mostly imported into London from the Levant). In south-east Lancashire however, due to the influence of wealthy cloth merchants around the Manchester area (and later helped by growing imports of raw cotton into Liverpool from the new colonies in the Caribbean), the manufacture of fustians began to take hold.

In the late 1500s Manchester families such as the Tippings, Chethams, Booths and Wrigleys made their wealth from trade in linen and woollen cloths. However, in the early 1600s they began to turn their attention to cotton. In 1610, George Tipping and George Chetham (originally Tipping’s apprentice) entered into a partnership in part for the “buyinge and sellinge of…Cotton Yarne or Cotton Wooll”. Chetham during his apprenticeship had been based in London, and it is clear that during the partnership he would purchase raw cotton in the capital from where it would be transported to Manchester for turning into cloth. Tipping and Chetham would pass on the raw cotton to artisan weavers and their families who would convert it into woven cloth. As well as ‘giving’ the raw materials to the weaver, the clothiers also extended credit, thus making the weaver indebted to the clothier, and obliging him/her to sell the finished cloth back to the originating clothiers. We can clearly see here the beginnings of the worker-employer relationship that would underpin the cotton manufacturing industry of south-east Lancashire in the centuries to come, and which was in great contrast to the independent farmer/clothmaker of the woollen industry in Yorkshire at this time (see Chapter 3).

As well as being pivotal in the foundation of the cotton manufacturing industry in Britain, the Chethams also left behind lasting landmarks in Manchester: Humphrey (George’s brother) would carry on the cloth trading business following George’s death (1626), and would go on to be High Sheriff of Lancashire (1635), and founder of the school and library that still bear his name. In Oldham just 6 miles up the road from Manchester, another local family of clothiers was the Wrigley family who came to own Chamber Hall (just down the road from Joshua Cudworth’s Werneth Hall). Henry Wrigley (see Ministers and Merchants…, under Miscellany) originated in Salford, but bought lands around Oldham and Middleton. Like the Chethams, Henry Wrigley was active in the fustian trade, and like Humphrey Chetham he would become High Sheriff of Lancashire (1651).

In his 1817 history of Oldham, James Butterworth describes Chamber Hall as a handsome stone mansion in the grounds of which was a detached building bearing the inscription “H.W. 1648”. In many ways the arrival of Henry Wrigley at Chamber Hall, and the carving of his initials on this building, mark a major shift in the economic and political control of the area – from landed gentry to successful, self-made businessmen. Chamber Hall had been the manorial seat of the Tetlow family who had owned land in the area from the early 14th century. In 1320 Robert de Oldham had granted to Richard de Tetlow lands in Werneth. It is thought that the Tetlows and Oldhams were related by marriage, and the Oldham family’s ties to the manor of Werneth were even older than the Tetlow’s to Chamber. Around 1224, Alward de Aldholm (or Ailward de Oldham) held 2 oxgangs (30-40 acres) of land in Werneth by payment of fees to William de Neville, and until the late 14th century Werneth Hall remained the ancestral home of the Oldhams. The last of the Oldhams, Margery, married John de Cudworth, and following her death in 1383 the manor passed to her son John de Cudworth. The Cudworth’s then continued as lords of the manor until Joshua Cudworth (see above) sold the property to Sir Ralph Assheton of Middleton in 1683.

In addition to Chamber Hall in Oldham, Henry Wrigley would also purchase the Langley Hall estate in Middleton from yet another of the landed gentry, Richard Radclyffe. In his trading practices, Wrigley, like the Chethams and other cloth merchants, used the methodology of extending credit to weavers and providing the raw materials, and then buying back the finished cloth. From 1631 onwards, records of Wrigley’s business indicate that he was a creditor of numerous fustian weavers and chapmen (small cloth dealers) of Bolton, Kearsley, Bradford (Manchester), Hopwood and Hollinwood. In times of hardship, these weavers often found themselves in great debt to the middlemen merchants, and heavily dependent upon them. For example, in a court case brought by a Blackburn cloth merchant against defaulting weavers, it was stated that cotton had been advanced to weavers “…on trust and credit…without any security other than their promise to pay”. It doesn’t seem too far-fetched to assume that John Dalton Jr., like other weavers of the time, was indebted to such a middleman as George Chetham or Henry Wrigley. John was most likely an artisan weaver, working in his own home, being supplied with raw cotton by a local clothier, and employing his wife and family to card and spin the yarn for weaving on his loom.

Oldham after the Restoration

Following John Jr.’s baptism in 1664, no further Dalton christenings are recorded until the first of John Jr.’s children, also John, was baptized on the 22nd September 1689. Through the 1690s and early 1700s there then follow numerous baptisms of the children of John Jr. and his brothers (James, coal miner of Tyth Barn, and Robert, labourer of Priesthill). These observations suggest to me that John Sr. was perhaps the first Dalton resident in Oldham, and that the majority of subsequent Oldham Daltons descend from John and Ellen. The late 16th and early 17th century was a time of much change in Lancashire; during the Tudor period the county was a relative back-water with a reputation for “insularity, ignorance and evildoing” (Walton). Nevertheless, there was plenty of un-enclosed land in the foothills of the Pennines that attracted landless migrants who proceeded to reclaim the waste and parcel out the land amongst themselves. Between 1563 and 1664, the population of the county is estimated to have increased from about 90,000 to 160,000, with a large proportion of this increase occurring in the south-eastern corner around Manchester. It’s possible that John Dalton Sr. was part of this influx, perhaps moving from the home of the first Daltons in the north of the county (Dalton-in-Furness) to the south-east seeking work, a little land and a better life.

On the other hand, the lack of records for Daltons prior to 1664, and the abrupt emergence of the family name in Oldham parish records, may have come about because of changes in legislation; in particular, the institution of the Clarendon Code and implementation of the Poor Relief Act (sometimes referred to as the Settlement and Removal Act). During the period of the Commonwealth and direct parliamentary government (1649-1659), the Puritans had tried to eliminate many practices of the Church of England that they associated with Catholicism; however, following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the Parliament of Charles II passed the Act of Uniformity (1662). This Act, together with three other Acts, made up the Clarendon Code that was intended to remove all influence of the Puritans over the workings of the Church, and to prevent Puritans, or other Dissenters, from holding public office. The Act enforced the use of the Book of Common Prayer in the Church, declared that all ministers must be ordained in the Episcopal (Anglican) church, and prevented anyone who didn’t observe the Act from serving in government or church offices. As a result, more than 2,000 ministers refused to comply and were expelled from the Church (the ‘Great Ejection’). Amongst those ejected was the vicar of Oldham parish church, the Rev. Robert Constantine (see Chapter 3, and Ministers and Merchants…, under Miscellany). Another consequence of the Act of Uniformity was that it forced the majority of citizens to baptize their children in the Anglican church; furthermore, in the same year, the government passed the Poor Relief Act which was designed to establish which parish a person ‘belonged to’. If a person moved from one parish to another he would have to obtain a Settlement certificate from his originating parish. Then if he needed poor relief, the originating parish would be responsible both for removing him back to the original parish and also providing him with financial support. These factors may well explain the sudden appearance of many families in the parish registers, including the Daltons in the records of Oldham parish church.

The Glorious Revolution

John Dalton Jr. and his brothers, James and Robert, would have grown up in a period of some political and religious unrest. The civil war had ended in 1651, and the monarchy had been restored with little violence just four years before John’s christening. Nevertheless, there was still some disquiet amongst Protestants that the King was too sympathetic to the Catholic cause. In Scotland and the north of England there were movements to remove the king several years after the restoration (e.g., the Northern Rising in the West Riding in 1663). Manchester, Bolton and Rochdale had always been Puritan strongholds, the south-east Lancashire region remaining Puritan throughout the three civil wars. Charles Worsley, a linen draper, and the first MP for Manchester, was a Major General in Cromwell’s army. Indeed, the Lancashire textile industry was largely built up by Puritans and Dissenters, and the wealthy clothiers often provided support for the ejected ministers – a prime example being the aforementioned Henry Wrigley who fervently supported Robert Constantine in his disputes with respect to the ministry of Oldham parish church (see Ministers and Merchants…, under Miscellany).

It wouldn’t be until the year of John Jr.’s marriage to Sara Wylde (1689) that the Protestants would be truly satisfied that all Catholic influence had been removed from the realm, and Non-Conformists would finally gain the freedom to observe their faith as they saw fit. This was the year in which the crown was offered to Mary (daughter of the deposed James II) and William of Orange by Parliament following William’s invasion and the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of the previous year. The ascent of William and Mary to the throne was closely followed by the Act of Toleration allowing the Rev. Constantine to establish Greenacres Independent Chapel (see Chapter 3).

Compared with the great turbulence that their grandparents must have endured during the time of the Civil Wars, and the political and religious unrest that followed the Restoration, the children of John Jr. and Sara would have grown up in a time of relative peace. William and Mary passed the Bill of Rights which established the rights of Parliament to govern, the freedom of speech of MPs, the rights for free and regular elections, and perhaps most importantly instituted limits on the ability of the monarch to interfere with Parliamentary democracy.

John and Sara’s eldest son, also John, would follow in his father’s footsteps. In the Giles Shaw manuscripts it is stated in the record of the christening of Edmund Dalton (b. 1714; see family tree at the end of the chapter) that Edmund’s father, John, is a weaver of Cuck stoole pitts (thought to be the site of the village ‘cucking’ or ducking stool; an instrument of punishment for persons found guilty of scolding [public nuisance] or back-biting). In the period from 1725 to 1781, records of baptisms at Oldham parish church show that amongst the occupations of fathers about half were weavers. Indeed, Edmund himself would also take up the trade of weaver, and likewise three of his four sons; thus, making four generations of Dalton weavers. I’m not sure of the location of Cuck stoole pitts and whether this was the site of the cottage rented by John Dalton in 1681. However, the family seem to have moved from this cottage by 1742. Records of the Lister family (then occupants of Werneth Hall) show that the ‘Dalton cottage’ in Priesthill is now rented by a John Wallwork for 6s per annum (although he is in arrears of £1 13s 4d!) The four generations of Dalton weavers span the period from about 1685 to 1800. By the beginning of the 19th century Oldham’s population had grown around 10-fold from about 1100 in 1666, reaching over 12,000 in 1801 (see Appendix 2). I’m not sure what kind of property the Dalton family lived in; however with the growth of the town, working people may well have been housed in adjoining properties as shown in the picture of houses in Dobcross that were probably built in the mid 1800s – somewhat between individual, self-contained cottages and the massed, terraced housing of later years.

Over this time perhaps the greatest challenge to working people was the relative decline in their standard of living. Thorold Rogers (1884) has argued that the golden age for British working people came at the end of the 15th century and early parts of the 16th century. This was a time when land, although technically owned by the lord of the manor, was used in a communal fashion for the benefit of the whole village (a feature retained from Anglo-Saxon traditions pre-dating the Conquest). However, in the middle of the 16th century the process of enclosure and the ‘privatization’ of land led to a decrease in the land available for common labourers and artisans to supplement their earnings with chickens, the odd pig and home-grown vegetables. At the same time prices, having fallen through the 1400s, began to rise. Rogers states that in the mid 1500s the price of meat rose three-fold and that of dairy produce and corn about two and a half times compared with an increase in wages of only one and a half times. By 1593 Rogers estimates that it would take a labourer a whole year to earn enough money to buy a quantity of grain that he could have bought with 15 weeks wages in 1495, a more than 3-fold decrease in purchasing power.

The next century would be no better for working people. If the erosion of land available for communal usage and increase in prices were not enough, next came the imposition of taxes. In comparison with continental Europe, Britain at this time had relatively low levels of taxation; there had always been tithes and fines associated with property, and there were some duties applied to exports and imports; the latter mainly to protect home businesses from foreign competition. However, taxes applied to consumer goods were mostly non-existent; nevertheless national demands increased to such an extent in the middle of the 17th century that new streams of revenue were required to avoid the crown/government from going bankrupt. Charles I had a great fondness for the arts, as well as a need to maintain a strong fleet; together with expenses incurred by the first Civil War, these factors led the Long Parliament in 1643 to create the ‘excise’. This tax was first applied to ale, cider and perry, but it was followed shortly by more duties on salt and butcher’s meat, and in 1645 hats, starch and copper were added to the list of taxable goods. Although the Hearth Tax (1662) and the Window Tax (1689) probably had little effect on the families of labourers and poorer artisans, further taxes on malt, hops, soap, leather, coal, paper and candles followed. By 1715 the government was earning about £2.3 million in excise duties on consumer goods. Clearly, these taxes must have had a considerable effect on the cost of living of working people. From the ‘golden age’ for the English working-classes around 1500 to the end of the 18th century, wages for the working man increased considerably, but wages didn’t keep pace with the cost of living. As a proportion of his wages, the artisan weaver would have seen his rent increase almost 2.5x, likewise staple foodstuffs such as milk (1.7x) and flour (4x) [see Appendix 3]. Interestingly, the cost of beer stayed almost constant over the same time period!

The Dalton family break with weaving

As already mentioned Edmund Dalton (b. 1714) would have four sons, three of whom were weavers. The youngest of these sons, also Edmund (b. 1752), was also a weaver, but his son John (b. 1780; Elizabeth’s father) would break with the Dalton weaving tradition in becoming a hatter (and latterly, a publican). Examination of the occupations of the parents of children baptized in Oldham parish church in the 18th century reveals that there are very few hatters recorded before 1750, but in 1766 there are 11, in 1780 there are 34. By 1817 James Butterworth lists 25 hat manufacturers in his History of Oldham, and in 1841 his son Edwin estimates that almost 3,000 Oldhamers are employed in the hatting industry. Clearly, hatting saw a sizeable increase in the town in the latter part of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Hatting was a trade that was quite extensive around Manchester, particularly in Denton and Stockport. In Oldham, the type of hats made were felt hats originally made from high-quality, fine wool from Spain or goat’s wool from Germany or the Levant (sometimes called ‘camel hair’), but latterly from beaver pelts that were increasingly imported from North America.

John’s break with the Dalton weaving tradition may have had something to do with the economic conditions at this time and the great change in fortunes of artisan weavers. Alan Booth (1977) states that wage levels in the cotton industry in 1795 were in steady decline, and William Rowbottom’s diary in 1793 records: “The relentless cruelty exercised by the Fustian Masters upon the poor weavers is such that…it is nearly an impossibility for weavers to earn the common necessities of life so that a great deal of families are in the most wretched and pitiable condition.”. As mentioned previously, in contrast to the woollen industry in the West Riding, trades such as weaving and hatting in south-east Lancashire were increasingly dominated by manufacturers who employed a number of workers to make products from the raw materials that the manufacturer provided. This business model led either, as noted by Rowbottom, to impoverishment of the workers or, as we shall see later, to disputes between employer and employee.

As well as depression in wages in the Oldham area, the 1790s were also a time of poor harvests, and a consequent increase in the cost of food, particularly wheat, barley, oats and flour. The combined effect of the decrease in earnings and the increased cost of food led ultimately to numerous food riots across the country; and Oldham was no exception with riots occurring in July and August 1795 (over the cost of oatmeal), October 1799 (flour and oatmeal), February 1800 (flour) and again in May 1800. The increase in grain prices was certainly caused by poor harvests, but there was also a contribution due to the growth in the numbers of middlemen who purchased grain from farmers and then sold it on at an inflated price to the millers. Indeed these grain dealers, or ‘swailers’, were the main target of the most violent aspects of the riots.

In Oldham the houses of John Taylor (grocer, Chadderton), Richard Broom, Joseph Bradley (corn dealer of Henshaw St), Robert Mayall and Abraham Jackson (grocer of Cheapside) all came under attack. Nevertheless, although given the name ‘riots’, many events occurred without any violence or injury. Most of the rioters appeared to be more interested in the price of food rather than carrying out violent assaults on those perceived to be profiteering. For example, in 1799 and in 1800 mobs in Oldham seized flour and meal from dealers, sold the ‘confiscated’ goods and then gave the proceeds to the grocers! Many of these ‘rioters’ were women, and it is clear that they were more interested in feeding their families at a price they could afford, rather than stealing and causing damage. In fact many people merely threatened violence to try to get a reduction in food prices – in Blackburn a crowd paraded through the streets carrying large sticks, but then didn’t do any damage. In Oldham, and several other Lancashire towns, handbills threatening disruption were pushed under selected doors, and posters were placed strategically around the town. Such printed material was thus a warning to the local authorities to do something about the high cost of food, but with the intention of avoiding violence.

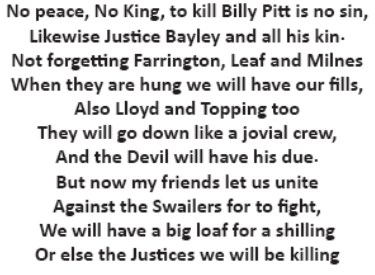

These latter actions (protest marches and pamphleteering) show a certain degree of organization. The government became noticeably worried about such evidence of collaboration amongst working people. The revolution in France had just taken place in 1789, and English, radical republicans such as Tom Paine were making noises about the unfair nature of the Monarchy and the corruption of British politics (rotten boroughs, etc.). The Government took to planting spies in organizations such as the London Corresponding Society (LCS) and Hampden Clubs (associations that advocated constitutional reform) to try to undermine any activities they interpreted as seditious. More seriously, Parliament was forced to suspend Habeas Corpus (act of Parliament that prevents imprisonment of anyone without due process of the law) both from May 1794 to July 1795 and from April 1798 to March 1801. Despite, or perhaps because of, these tactics the atmosphere in the country grew increasingly unsettled. In November 1800 a poster was placed on a toll-gate in Manchester declaring:

Billy Pitt was, of course, the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger; Bayley, Farrington and Leaf were local magistrates, Lloyd and Topping barristers, and Milne the town clerk. Swailers were the middlemen who were seen to be profiteering from the sale of grain and flour between the farmer and the consumers.

In March 1801 Parliament reinstated Habeas Corpus which removed the chances of being arrested without cause. As a result, a number of meetings of working people took place across south-east Lancashire. One such gathering, held between Oldham and Rochdale under the cover of darkness, had the agenda “An equal representation of all the people of England by Universal Suffrage; A reduction of the National Debt; A lowering of [the cost of] Provisions of all sorts”. In Manchester a group of men were arrested in a meeting at which the topics of conversation were the continuation of the war (Napoleonic), the high prices of provisions and the regulation of wage levels. Booth (1977) speculates that these meetings represent the culmination of the separate struggles of the food rioters, political radicals/reformers, and trade unionists; and that from now on these three strands of public protest would become intimately intertwined.

A Dalton in prison

Another measure brought in by Pitt’s government, to prevent the organization of opposition to their rule by working men, were the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800. These acts basically made any form of collective bargaining or trade unionism illegal. Thus the working people of Oldham (and other industrial towns in Lancashire) were left virtually powerless to do anything about their predicament. They were faced with rising food prices and employers who could reduce their pay on a whim. They had no political representation, in 1811 Cornwall had an MP for every 4,750 citizens whereas Oldham with a population of about 30,000 had no MP. In addition, Pro-reform societies (e.g., the LCS) were suppressed by the use of the law, the infiltration of spies or the muscle of the military. And now, the Combination Acts meant that any opposition through trade unions was prevented.

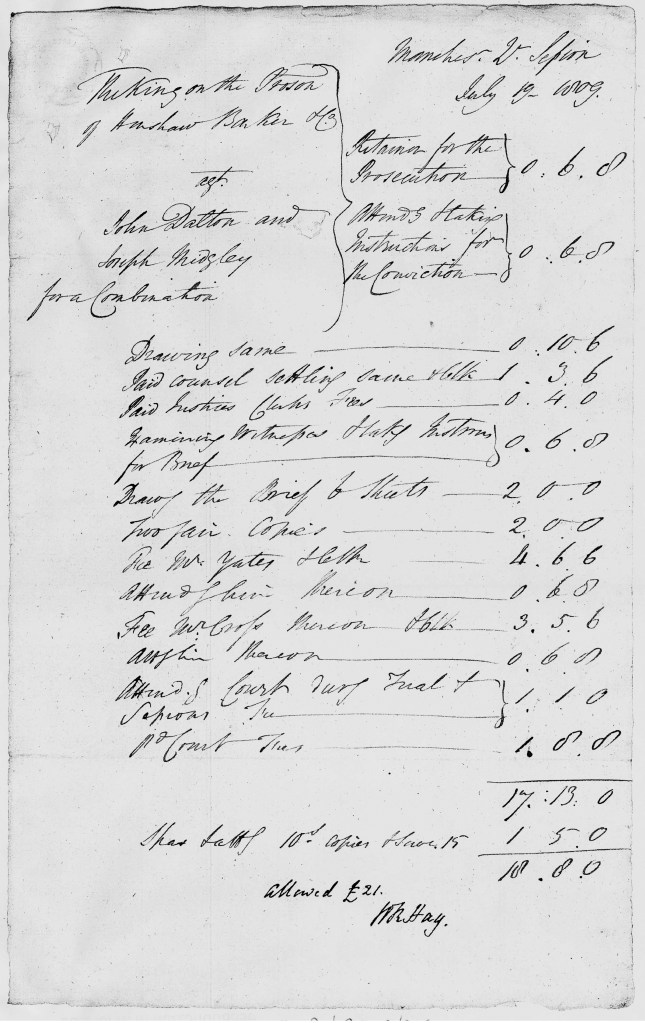

Of particular interest to me, however, was the discovery that in 1809 the Combination Acts had been used to prosecute one John Dalton, hatter, of Oldham. In July of that year, John Dalton and Joseph Midgeley were indicted “for a Combination” (see bill of prosecution, below) following an industrial conflict between some hatters and a local hat manufacturer (Mr. Barker of Henshaw & Barker). According to Edwin Butterworth (1856), the argument arose because of the increasing employment of women at the ‘plank’. The male hatters believing that this practice led to a lowering of wages, and thus a decrease in their earnings. During the dispute, Dalton and Midgeley were accused of using ‘intimidating language’. They were subsequently brought before the magistrates at the Salford Hundred mid-summer Quarter Sessions held in Manchester. The pair were convicted and fined £20. However, neither could afford the fine, and in lieu of payment, Dalton and Midgeley were imprisoned in the New Bayley prison for two months.

The pair seem to have been looked upon as heroes by their fellow workmen, William Rowbottom records in his diary on 19th September that, on release from prison, Dalton and Midgeley arrived at Coppice Nook in a chaise and there they were met by several hatters who “…took the horses out of the carriage and drawed them in great triumph through every publick place in Oldham to the great mortification of their masters…”.

The fight for Reform

Workers’ dissatisfaction with their working conditions, the high cost of food and their lack of political influence would continue over the next 10-20 years. These were turbulent times with growing numbers of political meetings in the town. The meetings follow a general pattern across the country reflecting a dissatisfaction with the parliamentary system. As a result there were numerous gatherings proposing reform, the first of these in Oldham took place on Bent Green in September of 1816. Early the next year there were two more, larger, meetings at the same location in January and February. In response to these meetings, the authorities appointed a number of special constables and drafted in the military, stationing soldiers from the 54th Regiment of Foot in a temporary barracks in Fogg lane, and calling up a party of the 13th Light Horse. At this time, still fearing a revolution such as had occurred in France, the government again suspended Habeas Corpus. On the 10th March, the radical reformers assembled once again on Bent Green in Oldham and set out to march to London via Manchester to present their grievances to Parliament and the Prince Regent. Perhaps surprisingly, the amassed special constables and soldiers took no action, and allowed the protestors free passage to Manchester. Several of the participants covered their shoulders with blankets such that the march has been dubbed the ‘Blanket March’, and the participants ‘Blanketeers’. The marchers from Oldham met up with others from the surrounding area on St Peter’s fields in Manchester. It is said that the organizers stressed the importance of lawful behaviour, but the magistrates still read out the Riot Act, the assembly was broken up by the King’s Dragoon Guards and the ringleaders arrested. Some men still tried to continue the march, but they were pursued by the cavalry on the road to Stockport and many suffered sabre cuts and one man was shot dead.

There was some disquiet about the behaviour of the magistrates, but they were later able to justify their actions when an apparent conspiracy was uncovered at the Royal Oak in the Ardwick Bridge area of Manchester on the 28th March. Eleven conspirators were arrested at this ‘secret’ meeting, two of whom Edwin Butterworth says were from Oldham, a William Kent of Street Bridge (between Royton and Chadderton), and another named Taylor. According to the authorities the aim of the conspirators was to free the arrested Blanketeers and take over the running of the city. In the following days, the deputy constable of Manchester, together with a contingent of dragoons, visited the Oldham area to round-up more conspirators, amongst these were members of the local Hampden Clubs (including Samuel Bamford, a noted radical and founder of the Middleton Hampden Club), Edward O’Connor a publican from Chadderton, and George Howarth, a labourer from Royton, who was arrested for using threatening language. Bamford was indicted for treason, but was eventually released on his own recognizance – presumably from lack of evidence.

A few months later, however, a more serious event occurred that spelled the end of the Hampden Clubs. This was the so-called Pentrich Rising in Derbyshire which involved 200-300 men from both Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire who were gathered together by the leader of the local club, Thomas Bacon, and the ‘Nottingham Captain’ Jeremiah Brandreth (a distant ancestor of Gyles Brandreth). Unfortunately for the group, another of the ringleaders (William Oliver) turned out to be a Government spy. As a result of Oliver’s treachery the ‘revolutionaries’ were intercepted on their way to Nottingham by the 15th Regiment of Light Dragoons. Several men escaped, but most were finally rounded up and put on trial; three (including Brandreth) were hanged, eleven were transported for life and another three for fourteen years.

The Seditious Meetings Act of 1819 would essentially outlaw societies such as the Hampden Clubs, and send radical reformers underground. The more moderate reformers would create the Patriotic Union Society which was the body that organized the ill-fated meeting on St Peter’s fields on the 16th August 1819 — PETERLOO. Amongst the estimated 70,000 that gathered in Manchester that day were about 10,000 from the Oldham area (Oldham, Royton, Crompton, Mossley, Lees and Saddleworth). Four people were killed on the field itself, with at least 14 others dying later of their wounds. One of those that died on the field was John Ashton of Cowhill who carried the black banner of the Lees, Mossley and Saddleworth Union; others from the area that died were Thomas Buckley of Chadderton, Edward and William Dawson of Saddleworth, and John Lees of Oldham who, ironically, had fought at the Battle of Waterloo. Amongst those arrested after the meeting, along with ‘Orator’ Henry Hunt, was the founder of the Oldham Hampden Club, ‘Doctor’ Joseph Healey.

In response to the tragedy of Peterloo, Percy Byshe Shelley wrote his famous poem the Masque of Anarchy. Many years later, Harvey Kershaw wrote more simply, but no less poignantly:

There’s no way of knowing whether John Dalton was present at any of the meetings on Bent Green, or whether he travelled to Manchester that fateful day. His involvement in that earlier industrial dispute may show him to be an activist; on the other hand, as a result of his previous imprisonment he may well have had to keep his head down and out of trouble.

Another employment change for the Dalton family

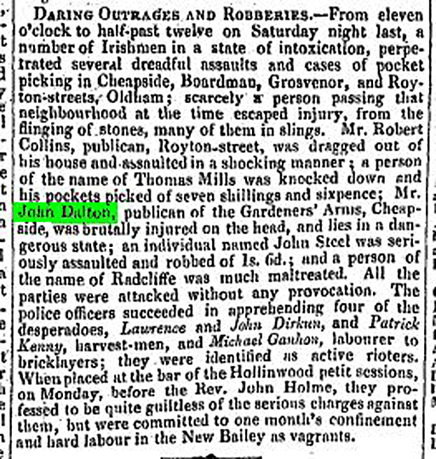

Five years after Peterloo, John is still a hatter according to the record of his son William’s christening on the 18th April 1824; however on the 15th September that same year William Rowbottom’s diary records that John Dalton of Priesthill was granted an alehouse licence, and Rob Magee (1992) states that John was a shopkeeper and hatter in Cheapside (Priesthill would later be renamed Cheapside) who opened a pub called the Gardeners’ Arms. Around this time (1824-1830, see E. Butterworth, pp. 188-195) Oldham began to undergo significant changes: in its population, in its streets and buildings, and in its industry. Old dilapidated houses on the High Street were taken down to make way for a new market place, an Act of Parliament (1828/29; Local and Personal Act, 9 George IV, c. xcix) was obtained to demolish the old church and build a new one (completed in 1830), and Collinge & Lancashire would install the first power looms in Oldham at their manufactory on Glodwick Road.

Nevertheless at the end of 1825, England would enter a severe economic depression leading to widespread bankruptcies and unemployment. Butterworth records how, in early 1826, the “distressed condition of the people manifested itself in riots in various places…”. This depression occurred as a result of the financial crash at the end of 1825. The Napoleonic wars had seen the first introduction of income tax to fund the government’s debt caused by the expense of the conflict; however, following Waterloo and the end of the war, income tax was abolished (1816). As a result government debt increased dramatically. Furthermore, the war years had been extremely profitable for the financial sector, and confidence in the stock market led to increasingly speculative investments and banks providing risky loans to speculators (ah… plus ça change…!). Ultimately this activity, coupled with increasing government debt, and the failure of the Bank of England to act as ‘lender of last resort’ led to a debt bubble which eventually burst causing the failure of 70 banks. As a result, Butterworth reports that “…the really wealthy found it almost impossible to meet their immediate engagements.”.

In April and May of 1826 the larger cotton mills with power looms became a major target of the riots; those of Milne & Travis in Royton and John Clegg in Higher Crompton suffered major damage to their looms. The machinery of Collinge & Lancashire on Glodwick Road was only spared by the protection of the Oldham Cavalry, the Cheshire Yeomanry and the reading of the Riot Act. In an effort to curb the riots, the Government provided £500 for relief of the poor in the manufacturing districts, including Oldham. Further local contributions provided food and relief for the most distressed operatives. Nevertheless later in the year, mill owners reduced the wages of the cotton spinners leading to turn-outs (strikes). The employers resorted to employing black-leg labour, referred to by the strikers at the time as ‘knobsticks’. Several skirmishes took place at the Collinge & Lancashire mill between the turn-outs and the knobsticks resulting in the intervention of the military, further readings of the Riot Act, and the prosecution of several turn-outs at the Salford Quarter Sessions. The strike was to last almost 4 months, but finally the majority of operatives had to return to work, accepting the reduced wages that they had struggled to avoid. Some strikers still held out, but Butterworth records that the last hold-outs (about 28) were eventually arrested and imprisoned for terms of 9-18 months.

However, the next year would see an improvement in the economy, followed in subsequent years by a large increase in the number of cotton mills (31 in 1821 had increased to 62 by 1831) and, according to Butterworth, the fastest increase in population in the town’s history – a nearly 50% increase between 1821 and 1831 (from ~34,000 to ~50,500, if Royton, Crompton and Chadderton are included). Oldham was becoming a boom town on the back of its increasingly important business of cotton spinning.

In 1832, Parliament would pass the great Reform Act and Oldham would finally get its first MPs (Oldham by this time had a population equal to the combined population of the 38 smallest, represented boroughs!). Surprisingly, the voters of Oldham elected two radicals – William Cobbett and John Fielden – with landslide majorities. The unusual success of the radical politicians in Oldham has been attributed to various factors amongst which were the threats by working people to boycott the businesses of voters, the strength of anti-slavery sentiment amongst the, mostly Dissenting, electors that was in contrast to the beliefs of the Tory and Whig candidates and, perhaps most importantly, to the poor quality of the opposition candidates.

The next decade would see the economy of the town fluctuate with a number of industrial disputes, including a major strike in 1834 and a turn-out of spinners in 1837. The prospects for artisan weavers were certainly not good. However on the whole, the town prospered and those operatives employed in the cotton mills of Oldham were some of the best paid workers in the region. Perhaps, it wouldn’t have been such a bad time to be a publican in a town full of thirsty mill workers!

John Dalton would run the Gardeners’ Arms until about 1840, by which time Oldham had added another 32 cotton mills, and the population of the town (including Royton, Crompton and Chadderton) had increased to over 60,000. In the 1841 census the Gardeners’ Arms is in the hands of John’s son-in-law, John Wood (husband of John’s daughter Sally). The newspaper article below may explain why.

It’s possible that John never recovered from this assault, and left the running of the pub to his son-in-law. Magee records that Wood was licensed-victualler of the Gardeners’ only until 1842, and indeed in the 1851 census John Wood is listed as a cotton spinner of Furtherfield. Interestingly in this same census return, a John (18) and Joseph Thomas (16) are living with John and Sally Wood. The boys’ parents, Edward and Elizabeth Thomas, were both dead by this date, and John and Joseph had clearly been taken in by their aunt (Elizabeth’s sister) and uncle. I shall return to the boys’ stories in chapters four and five, but having looked at the origins of Elizabeth’s forebears, in the next chapter I’ll delve into Edward’s origins.