“I know and deeply deplore the sufferings which the working-men of Manchester…are called to endure in this crisis….Under the circumstances, I cannot but regard your decisive utterances upon the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism…I have no hesitation in assuring you that they will excite admiration, esteem, and the most reciprocal feelings of friendship among the American people.” — Abraham Lincoln, Letter to the cotton operatives of Manchester, 1863.

When I travelled to California in 1983 I was under the impression that none of my family had ever emigrated to America. My father had often said that he had wanted to take us all to Australia in the ‘60s when the government there were offering cheap emigration packages, but my mother hadn’t wanted to move so far from her friends and family, and so we had remained in England. Also, I knew that my dad’s uncle Jack’s son had gone to South Africa, but I wasn’t aware of any family member crossing the Atlantic. Indeed, it was more than 10 years after I returned to England that I discovered that a Thomas had beaten me to the New World by more than 100 years!

My great, great grandfather’s brother Joseph, his wife Mary and their young son Foster set sail on the SS England from Liverpool bound for New York in February 1869. They eventually settled in Philadelphia where they had two more children, both girls, Elizabeth and Ellen. Indeed Mary seems to have come from a very adventurous family who were unafraid to move residence to obtain a better life.

Immigrants to Lancashire

Mary’s father Foster Cowling was a farmer/cobbler born into a large family of tenant farmers in Silsden in Yorkshire at the start of the Regency. His parents James and Margaret had at least 12 children. Like the Daltons in Oldham in the first chapter, the Cowling family of Silsden can be traced back to the time of the Restoration and Act of Uniformity (see family tree below).

The Cowlings had farmed lands in Brunthwaite near Silsden for generations. Much of the land in these parts was owned by the Clifford family of Skipton Castle (and latterly the Earls of Thanet). In 1795 the records of the Earl of Thanet show a farm of 73 acres in the tenancy of Joshua and William Cowling, by 1836 the land had been divided into six separate properties held by different members of the family: William Cowling, 11 acres (annual rent = £17. 6s. 6d); Joshua Cowling, 5 acres (annual rent £8. 12s. 3d.); Samuel Cowling, 5 acres (annual rent = £9. 11s. 9d.); John Cowling (Woodsides), 49 acres (annual rent = £67. 10s. 7d.); Foster Cowling, cottage & garden (annual rent £4); John Cowling, 4 acres (annual rent = £5. 15s. 2d.).

At about the same time (1835) the West Riding electoral rolls reveal that James Cowling (b. 1776) is resident at Moorcock Hall; and in the 1841 census, James’s eldest sons James and John are both farmers at Moorcock Hall, Cringles, Silsden, and resident there with their parents James and Margaret. However, tithe maps of Oldham created sometime between 1840 and 1848 reveal that John is now running a 31-acre farm on Honeywell lane (annual tithe £1 11s 3d payable to the Rector of Prestwich cum Oldham; owner – Captain Reece). By the 1851 census, John is still the tenant of this farm and living there with him are his brother James, sister Margaret and their parents, James and Margaret.

The same tithe maps reveal that Foster is also now living in Oldham, tenant of a 51-acre farm on Glodwick Lows (tithe of £2. 12s. 3d. payable to the Rector of Prestwich cum Oldham; owner – Andrew’s executors). By the 1851 census, Foster has moved to a farm in Chadderton (West Hulme Farm, 34 acres). And by 1861 another brother has joined the immigrants to Lancashire – Coates Cowling is farming 19 acres in Greenacres (by 1871 this had increased to 61 acres, on Constantine Street).

It seems strange that a family with such farming traditions should move to an industrial town such as Oldham and carry on farming. One naturally assumes that migrants from agricultural regions to the developing urban areas moved to gain employment in the booming industries (in this case, cotton spinning). There may have been two reasons to explain the move. The first is the sheer size of the family, we can see the division of the land between different members of the family that occurred in Silsden between 1795 and 1836 as the family grew. It could be that the land just couldn’t accommodate James’s and Margaret’s increasing number of children. The second reason could be the much lower cost of land rental in Oldham. I’ve calculated that the family were paying an average, annual rent of about £1 12s 2d an acre in Silsden in 1836, by comparison John and Foster are paying about a third of this amount (10s 2d an acre) in Oldham in 1841-4 (assuming the tithes represent a tenth of the rental).

Emigration across the Atlantic

Ultimately in 1882, one of James’s and Margaret’s grandsons (Spencer son of Joshua) would extend this Cowling migration all the way to Australia, but before this last family move, two of Foster’s daughters would leave for the New World. The 1871 census reveals that a James Mellor is staying with his grandparents, Foster and Jane Cowling, on Ashton Road and that he was born in the USA (c.1861). His mother, Martha had married a William Henry Mellor in 1857 and had a daughter, Jane, in 1858. In 1871, Martha, like James is in Oldham and living on Radclyffe Street with Jane and another child, Thomas (b. 1866). However, William is not in the census, and Martha is described as a widow. There is also a birth record for a Margaret Mellor whose mother’s maiden name was Cowling born in 1863 (and died in 1864). If Jane was born before the emigration and Margaret after the family’s return, it would seem that the Mellor family’s stay in America was very short. The brief nature of Mellor’s stay in America may have been purely a matter of bad timing. April 1861 witnessed the outbreak of the Civil War in America, and it may have been that the Mellors decided that they would be better off returning to Oldham than staying in the States. Strangely the very thing that may have caused the Mellors to return to Lancashire may have motivated her sister, Mary, and her husband Joseph to go in the opposite direction just eight years later.

The Lancashire cotton famine

The Civil War brought great hardship to the working people of Lancashire. Indeed, this period is often referred to as the time of the ‘Lancashire cotton famine’. Significantly for Lancashire, the Civil War was accompanied by the blockade of the Confederate ports of the southern states by the Union navy. This blockade led to the complete cessation of raw cotton shipments to Liverpool. It has been estimated that Lancashire cotton manufacturers had about 4- or 5-months-worth of raw cotton stockpiled, but by October 1861 almost all cotton factories were at a standstill with numerous mill closures and mass unemployment. At the time the only help for the unemployed was relief provided by the Poor Law, either ‘in-door’ (admission to the workhouse) or ‘out-door’ (monetary help); however, out-door relief was restricted to those who were unable to work because of age or disability.

It soon became clear that the authorities would have to ignore the ‘labour test’ for the provision of out-door relief (Bateson, 1949). Additionally, in order to extend help to the high number of needy in the town, the Guardians of Oldham had to markedly increase the Poor Rate (tax paid by the owners of property in the town to support relief ) from 1s 3d to 2s in the pound. According to Arnold (1864) the number of rate-payers in the town was about 16,000 in 1862, this number was out of a total population of about 75,000. Even these measures were inadequate, later estimates suggesting that an increase in rates to 8s 3d in the pound would have been required at the height of the famine. Eventually a national relief fund (Union Relief Aid) was set up to which Oldham businessmen contributed £8,500, and which eventually amassed almost half a million pounds in aid (about £30 million in today’s money). An idea of the size of the distress in the town can be gleaned from the figures presented to Parliament in 1863 by the local MP, Sir John Hibbert. He said that out of almost 40,000 operatives over 11,000 were unemployed and almost 21,000 were reduced to short-time working, he added that 20% of the population was destitute and 25% of rate-payers had been excused payment of their rates. Further evidence of the extent of the crisis is shown in the figures for those receiving relief: in 1861 there were just 1,622, however in the next year the number rose to 28,851, declining in subsequent years to 8,871 in 1863, 9,165 in 1864 and back down to near pre-Civil-War figures of 1,892 in 1865.

These few years of severe hardship were compounded for Joseph Thomas and his wife Mary by the death of all their children. Tragically their three daughters, Elizabeth (aged 4), Jane (aged 2) and Fanny (5 months), all lost their lives to scarlet fever in the space of just 4 days (22-25 Nov 1863). Before the depression, Joseph, like his brother John (see Chapter 3), was working in engineering (iron planer), but on his daughters’ death certificates he is described as a tobacconist. It’s possible this change in occupation was a direct result of the economic downturn and the decreased demand for textile machinery. Then, on top of the struggle to make ends meet, comes the loss of their children. It’s hard to imagine how these dreadful events would have affected the couple, but it would be understandable if they had wanted to make a fresh start in another country far away from a place that held such unhappy memories. And this is exactly what they did. Following the end of the American Civil War and the birth of a son (Foster), Joseph and Mary decided to try their luck in America.

The Philadelphia story

The manifest of the SS England indicates that the family arrived in New York on the 15th February 1869. They travelled in steerage which would have cost about £6 (probably around three week’s wages for an iron planer), and the journey would have taken about 10-14 days from Liverpool, stopping in Queenstown (now Cobh) en route to New York. By June the next year (1870 census), the Thomases were living in the 27th Ward of west Philadelphia. According to the census, both Joseph and Mary are working in a cotton mill, and Joseph is already a U.S. citizen despite only being resident in the country for just over a year.

Historically, the city of Philadelphia is famous as the first capital of the United States (originally the United Colonies). The First Continental Congress was held in Carpenters’ Hall, Philadelphia in 1774. A year later the Second Continental Congress would be held in the city at the Pennsylvania State House. This location was also the venue in July of the following year (1776) of the writing and signing of the Declaration of Independence, as a result the Pennsylvania State House would become ‘Independence Hall’. Thus, Philadelphia became the site of the first governing body – Congress – before its removal to the purpose-built capital of Washington DC in 1800. By the time Congress departed for Washington, Philadelphia was the largest city in America and one of its busiest ports. However, in 1807 the government put an embargo on US exports, and together with the War of 1812, this led to a major decline in the maritime trade through the port of Philadelphia. In response, numerous factories developed around the city to manufacture the goods that were no longer being imported. As manufacturing increased, Philadelphia became the first major industrial city in America. Rather a fitting destination for the Thomas family coming from SE Lancashire, the centre of the world’s first Industrial Revolution.

Changes in family fortunes

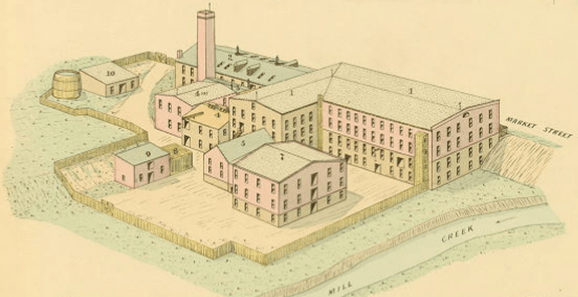

Indeed, by the latter half of the 19th century the largest industry in Philadelphia was textiles, with Philadelphia producing more textiles than any other US city; again almost a home-from-home for Joseph and Mary. In West Philadelphia at the time (see map below) there were several textile mills, but unfortunately the 1870 census doesn’t give street addresses and so I’ve no idea where in the 27th Ward (pink area south of Market on the map) the Thomases were living. By the next census, Mary is living with her children at 1265 N 52nd street (red circle on map). This address is in the 24th Ward (beige area north of Market on the map), so the family must have moved sometime before February 1880 (the record of Joseph’s death on the 24th February that year gives his address as 52nd and Kershaw streets). The closest cotton mill to this address is the Good Intent Mills at Market and 46th streets (no. 2 on map); perhaps, this was the mill that Joseph and Mary worked in. The owners of the Good Intent Mills in 1867 were Mr. James Lord & Sons; however, the mill had two occupants: a woollen shawl manufacturer (Mr. Kershaw), and a cotton yarn manufacturer (Mr. Lord). By 1883, the mill had three occupants, an M. A. Lord making carpet yarns from ‘soft cotton waste’ employing 23 hands (7 girls, 6 boys and 10 men; machinery included two self-acting mules with 442 spindles); Bottomly, Whiteley & Co. making woollen yarns, and Coates & Potts making both cotton and woollen goods employing 60 hands (20 boys, 10 girls and 30 men; machinery included two self-acting mules with 1224 spindles, as well as 80 power looms).

Following emigration, Joseph and Mary would have two more children, daughters Elizabeth Jane (b. 1871) and Ellen (b. 1876). In 1877 Ellen was baptized at St James’ church Hestonville. The township of Hestonville can be seen at the top of the map (above), and St James’ was actually on the corner of Kershaw and 52nd (see red spot on both maps, above and below); so, the family lived very close to the church. As mentioned above Joseph would die in 1880 leaving Mary with three young children (Foster, 11 yr.; Elizabeth, 8 yr., and Ellen, 3 yr.). The 1880 census records that Mary was not working at this time (‘keeping house’); interestingly, the family had a servant, an Irish woman called Mary Hogan. Joseph’s death is recorded as being due to ‘phthisis pulmonalis’ — consumption or tuberculosis being the most common cause of death in industrialized countries in the 19th century, accounting for about 40% of deaths in working-class families.

A few years after Joseph’s death, Mary would re-marry to a man named Robert Gormley. In 1885 Foster was confirmed at St James’s church, and in the same year Mary would give birth to another son, Robert Gormley Jr. Robert Sr was variously described as a sailor (1860) and a gardener (1870), but in the 1900 census (after Robert’s death; March 1900, aged 51), Mary is described as a saloon keeper at 1311 52nd Street. It’s interesting to note that between the two censuses Mary’s father, Foster Cowling, died in 1891. On his death, Foster’s estate was valued at £1518 8s 11d. According to Mary’s father’s will, the bulk of his estate, after payment of any debts, was to be left to his wife with several small bequeaths to his grandchildren in Oldham. However, after the writing of the will and just a week before Foster Cowling’s death (3rd June 1891), his wife Ellen (or Helen) would die. The will states that on her death, the estate was “…to pay to and divide the same equally amongst my children living at my decease and the issue of such of my children as shall be then dead…”. As we shall see later, Mary’s son Foster Thomas would make several trips to England around the time of his grandfather’s death. It’s possible that he was able to secure Mary’s portion of the estate, and that she used her inheritance to purchase this saloon.

By the time of his journeys to England in 1891-92, Foster Thomas had become an Attorney-at-law. This seems a remarkable achievement for the son of cotton-mill workers. Because of the loss of the 1890 US census (destroyed in a fire), it’s difficult to determine how, where or when Foster obtained his qualifications. In the USA in the nineteenth century there were few established Law schools, and most attorneys qualified by ‘reading’, sometimes under the supervision of a practising lawyer, but sometimes being self-taught. Abraham Lincoln practised law, and he is quoted as saying “It is a small matter whether you read with anyone or not. I did not read with anyone. Get the books and read and study them in every feature,…Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed is more important than any one thing.”.

Unfortunately, Foster didn’t practise for long, he was only 25 when he was buried in Mount Moriah cemetery alongside his father. In the Philadelphia Press of Saturday, December 16, 1893, there appears a notice of his death and funeral: “THOMAS – On December 14, 1893, FOSTER THOMAS, aged 25 years. Relatives and friends of the family, also Protection Lodge, No. 243, I.O. of O.F. and Longwee Tribe, No. 322, Improved Order of Red Men, are respectfully invited to attend the funeral from his late residence, No. 1315 North Fifty-second Street, on Sunday next, at 12 o’clock. Services at St. James’ Episcopal Church, Fifty-second Street and Kershaw Avenue. Interment at Mt. Moriah Cemetery.“.

Fraternal Societies

The ‘I.O. of O.F.’ is the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. The Oddfellows and the Improved Order of Red Men, like the Freemasons, are variously described as ‘fraternal organizations’ or ‘friendly societies’. Essentially, they began as societies that provided mutual help for members in the absence of state benefits or national insurance. The Grand United Order of Oddfellows was founded in Britain in 1798, but dissatisfaction amongst some of the members led to a split and formation of the ‘Independent Order of Oddfellows Manchester Unity’ (IO of OMU) in 1810, and an American branch of the IO of OMU was formed in Baltimore in 1819. The latter became independent of the British society in 1842 becoming the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.

The Order of Red Men grew out of the ‘Sons of Liberty’ who were involved in the infamous Boston Tea Party (1773). Later the Sons of Liberty split into several different societies; however, in 1813, a few of these groups in Philadelphia decided to come together to form a new society: ‘The Society of Red Men’, later (1834) to become the ‘Improved Order of Red Men’ whose membership was only open to “… a free white male of good moral character and standing, of the full age of twenty-one great suns, who believes in the existence of a Great Spirit, the Creator and Preserver of the Universe, and is possessed of some known reputable means of support.”. It seems that Foster Thomas would have fulfilled all of these criteria. From my limited understanding of these societies I would assume that Foster was introduced via a relative or close friend. I doubt that his father, Joseph, would have been a member, but it’s possible that his step-father, Robert Gormley was a member of one or both of these societies, or even that his grandfather, Foster Cowling, was an Oddfellow.

With regards to his grandfather, it is interesting to note that examination of ships’ manifests reveal a Mr. F. Thomas leaving Liverpool for New York on the 17th October 1891, and in the following February a Foster Thomas (age 23 yr., occupation lawyer) arriving in Liverpool from New York (each time on the SS Etruria of the Cunard Line). Foster’s grandfather died in the June of 1891, and his will was proved in August of that year (value £1034 16s 11d); however, the will was ‘resworn’ in March of the following year to a new value of £1518 8s 11d. It’s possible that Foster travelled to England in 1891 both for the funeral and to use his legal experience in helping to obtain his mother’s share of his grandfather’s estate. He, perhaps, had to then return in early 1892 to supervise the final tying up of the balance of the estate (sale of the house? – £483 12s).

Following her second husband’s death Mary would live another four years before dying of acute kidney disease and being buried with Robert in West Laurel Hill cemetery (1904). According to the 1900 census she was owner of the saloon bar that she ran, and so we must assume that the bar was left to her surviving daughters, Elizabeth and Ellen. However, the death certificate lists no occupation and the address is slightly different to the address in the earlier census (1317 vs. 1311 North 52nd). It’s possible that she had to sell the business due to ill-health, and that her daughters inherited next to nothing.

Mary’s daughters

In 1900 Ellen Thomas married a William Kennedy, and the 1910 census records that they had two children, but only one was still living – Mary Elizabeth born in November 1900. William was a patrolman or police officer at a time when many American cities were run corruptly by political party ‘machines’ for the benefit of the politician’s and their friends in big-business. A number of investigative journalists attempted to uncover such corruption with the idea of trying to reform the political systems in the big American cities at the beginning of the 20th century. One such journalist was Lincoln Steffens who published a series of articles in McClure’s Magazine that were collected together in a book entitled The Shame of the Cities (1904). One of his articles focussed on Philadelphia, calling it the “most corrupt and most contented” of American cities. Such corruption inevitably affected the police force. In the late 19th and early 20th century Philadelphia was dominated by the Republican Party machine which used the Police Department to maintain its control of the polls, and to act as an intermediary between the machine and the criminal syndicates that controlled gambling and prostitution in the city (see Elkins, 2021).

A new mayor in 1911 attempted to bring in reforms, including banning police officers from participating in politics while on duty, but the end of his mayorship in 1915 saw a return to the bad old days of the party machine. Such corruption was exacerbated by the introduction of Prohibition in 1920; however, yet another newly elected mayor, Freeland Kendrick, in 1924 vowed to finally clean up the running of the city. He appealed to the President for help, and as a result Calvin Coolidge sent a highly-decorated Marine General, Smedley Butler, to try to eliminate bootlegging, prostitution, gambling and police corruption. Because he didn’t have the power to sack police officers, Butler moved entire police units from one section of the city to another, in an attempt to destroy the police-run protection rackets and profiteering. Nevertheless, after just two years Butler eventually admitted defeat and gave up. Later grand jury investigations in 1928 and 1937 uncovered far-reaching corruption in the force with over 100 police officers and even a former mayor (Thomas B. Smith) being indicted.

Interestingly between the 1920 and the 1930 censuses, William Kennedy would leave the police force and become a bank guard. He may have retired – he was 56 in 1930 and would probably have already served more than 30 years as a patrolman. On the other hand it’s possible he, like other policemen, was forced out of the service following the grand jury investigations in 1928. By 1940 William had retired, and just a year later Ellen would die following a stroke (cerebral thrombosis) resulting from a chronic heart problem (myocarditis) that she had suffered from for the previous twelve months. William would live for another 17 years dying of heart failure in 1958. Ellen and William’s daughter Mary Elizabeth married a railway clerk, James Cassidy, in 1928. The couple would have a daughter, Mary Jane, who was born in 1930 and married a Joseph Boyle in 1947.

Mary’s other daughter, Elizabeth Jane, married a Joseph Kuhn in 1901, but died of a pulmonary haemorrhage just a few years after her mother at just 35 years of age. She died in Camden, New Jersey which is just across the Delaware river from Philadelphia, but her body was brought back to Philadelphia to be buried alongside her mother in West Laurel Hill cemetery. The 1910 census reveals Elizabeth’s husband, Joseph, and her step-brother Robert Gormley Jr living together at the Camden address in which Elizabeth died. Fascinatingly, Robert is working as a book-keeper in the ‘talking machine’ industry. One of the earliest companies set up to make records and gramophones was the ‘Victor Talking Machine Company’ of Camden, New Jersey. So, it would seem reasonable to assume that Robert worked for this company.

At the end of the last chapter we left my great, great grandparents John and Sarah, and I promised to return to their story later. So, the next chapter will focus on my paternal family line.