O Land of my fathers, O land of my love,

Dear mother of minstrels who kindle and move,

And hero on hero, who at honour’s proud call,

For freedom their lifeblood let fall.

— Land of my fathers or Hen Wlad Fy Nhadaum, by James & Evan James, 1856.

Before I started my research my father had always been under the impression that his grandfather, George, was born in Wales and had journeyed north to Oldham to play semi-professional rugby in what was then the Northern Union. However, I’ve already mentioned in the previous chapter that Edward Thomas and Elizabeth Dalton, George’s grandparents, were married in Oldham parish church in 1829. So, I think that the family stories about George should be taken with a large pinch of salt. If George wasn’t born in Wales, was his grandfather, Edward?

Well, it took me awhile to find it, but the registers of Middleton parish church revealed that George’s grandfather Edward was born in Chadderton and christened at St Leonard’s in 1808. So, two generations before George and we’re still in Lancashire. Edward’s father was also called Edward, a farmer or farmhand, and his mother was Ellen. This couple had also baptized Edward’s elder brother, John, at the same church 18 months before, but their next two children, Mary and Daniel, were christened in Oldham at St. Peter’s church. By this time (1810-12) Edward Sr. is described as a labourer (much later, in the records of his son Daniel’s marriage and his widow’s death, he is described as a wheelwright). Unfortunately, Edward Sr. would die before national records of births, marriages and deaths were instituted (1837) and before the first nationwide census in 1841; so, I have been unable to determine where he was born. However, his wife Ellen lived long enough to be recorded in the censuses, and in the 1851 census it states that she was born in Wrexham – Wales at last!

Ellen was born around 1772, and according to the Bishop’s transcripts of Oldham parish registers, Edward Sr. died in December 1819 in his 50th year, so he would have been born in 1770. I’ve been unable to find a record of the marriage of an Edward Thomas and an Ellen in the registers of Wrexham parish church in the period 1785-1805, or in the registers of St Leonard’s in Middleton. So, not knowing Ellen’s maiden name and not knowing where Edward was born, it’s proved impossible to locate a record of their marriage, or either of their births. Nevertheless, I think it is most likely that the couple were both born in North Wales, and it’s probable that that is where they were married. By the time that their son John was christened in Middleton they were both already in their thirties, so it is possible they arrived in the Manchester area with children born earlier in Wales; however, I’ve not been able to identify any likely candidates.

Of Edward’s and Ellen’s children baptized in Middleton or Oldham, John died in his teens (1819), Mary married an Edmund Greenhalgh in 1835 but died soon after (1837) and, as far as I can determine, without issue. The two sons who survived and had children were Edward, my great, great, great grandfather and Daniel.

Hyde Thomases

Daniel married a Jane Bowker at St. Michael’s church in Ashton-under-Lyne in 1840, and by 1851 the couple were living in Hyde with three young children, and Daniel’s mother Ellen. Daniel and his family were living in Flowery Field/Well Meadow and he was employed as an overlooker in the card-room of a cotton mill. At this time Hyde was dominated by the Ashton family that had several mills in the area. The family business was founded by Thomas Ashton Sr. who died in 1845 leaving the business to his two sons, Thomas Jr. and Samuel, who formed the Ashton Bros. & Co. Ltd. The Ashtons were Unitarians, a religious movement that was founded to try to unite all Non-Conformists – something that they never achieved. Unitarians generally believed in religious toleration and the idea that people should develop their own opinions and their own ways of worship. In addition, they believed that social evils were man-made and, as such, could be remedied by human intervention. They were very much in favour of social reform, and Thomas Jr. was a great friend of Samuel Fielden the son of John Fielden the radical MP for Oldham (see Chapter 1), a Liberal and a supporter of Parliamentary reform.

Not only did Thomas Jr. hold these beliefs, but he also put them into practice. He extended the small village begun by his father to provide decent housing for his workers. He also built one of the first day schools for the education of his workers’ children in Flowery Field. Notably, he and Fielden were instrumental in establishing Owens College – later to become the University of Manchester. The college had been founded in 1851 as a result of an endowment of £96,942 left in his will by the cotton-merchant John Owens. However by 1870, the college had grown to such an extent that it needed new buildings. It was Ashton and Fielden who raised the necessary finance, around £200,000, to build a new college on the present University site on Oxford Road.

Perhaps one of Thomas’s most remarkable deeds occurred during the Lancashire Cotton Famine that resulted from the American Civil War (1861-1865; see Chapter 4). In order to keep his workers in employment, he was willing to pay the highest prices for raw cotton. He also proceeded to build a new mill (Throstle Bank Mill) — reportedly keeping his workers in full employment, both in making the bricks and building the mill. He would later become the first mayor of Hyde (1881) and his son, another Thomas, the town’s first MP in 1885 (later Lord Ashton of Hyde).

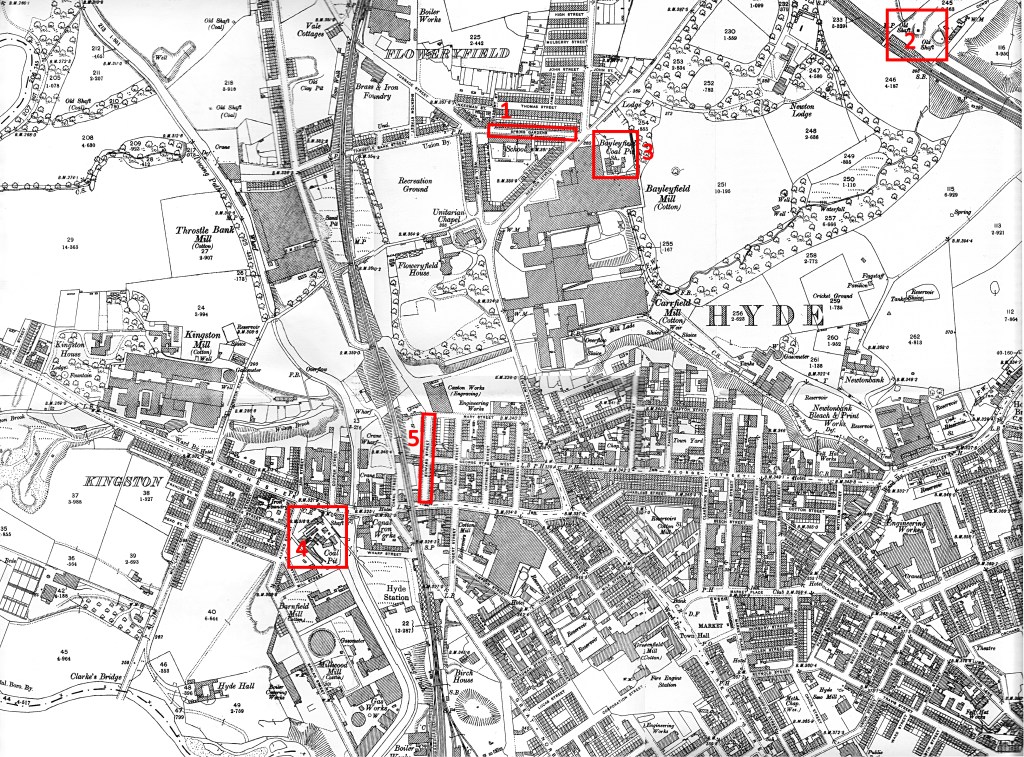

In 1835 Andrew Ure wrote “The houses occupied by Mr. T. Ashton’s work people [at Hyde, near Manchester] lie in streets, all built of stone, and are spacious; consisting each of at least four apartments in two storeys, with a small back yard and a mews lane. I looked into several of the houses and found them more richly furnished than any common work people’s dwellings which I had ever seen before.” It could have been hearing about the Ashtons, and in particular the nature of the way they dealt with their workforce, that Daniel decided to move to Hyde and get a job in Thomas’s mill. Indeed in 1841, he and his family are living in Spring Gardens (no. 1 on map below) in the heart of the Ashton’s development close to Well Meadow and Flowery Field.

Chartism and the Anti-Corn-Law League

Perhaps surprisingly, this part of Manchester would be at the centre of one of the major industrial disputes of the century. In the first chapter I’ve already mentioned the food riots of the 1790s and early 1800s, and the great unrest about the lack of Parliamentary representation for the northern industrial towns. The latter highlighted by the massacre on St Peter’s Fields in 1819. I also mentioned the large decrease in mill workers’ wages following the great depression of 1826, and the major strike in Oldham in 1832. That same year would see the passing of the Great Reform Act and a broadening of the franchise, thus increasing the number of MPs for the northern towns (two in Oldham). However despite the Reform Act, some towns still lacked representation in Parliament and many men still didn’t have a vote. For example, at this time Stalybridge and Hyde would have been part of North Cheshire, a large, mostly rural constituency stretching from Runcorn in the west to Northwich in the south and north-east to Stalybridge, but represented by just a single MP. This situation led to the creation of the “People’s Charter” by men such as Thomas Ashton and Samuel Fielden to try to improve democracy in the country. The charter had over three million signatures, including about 10,000 from Stalybridge, and proposed, amongst other things:

- Extending the vote to all men above the age of 21 (at the time only 18% of such men had a vote).

- Equalizing the size of constituencies by creating 300 electoral districts of equal population each with a single MP.

- Instituting a secret ballot.

As well as the discontent over Parliamentary representation, many workers still hadn’t seen their earnings recover to pre-1825 levels and were extremely dissatisfied with their poor wages. Edwin Butterworth (1856) reports that in the latter part of 1841 “…the cotton trade became more depressed than had scarcely ever before been known.”. In response, the mill owners began to slash wages by as much as 25%. And when the Charter was rejected, leaders of the Manchester Chartist movement, who were also leaders of local unions, encouraged their fellow workers to strike. The reasons behind the strikes being both better pay and also to force the Government to reconsider the Charter. It’s also been suggested that many of the manufacturers carried out these swingeing cuts in wages to deliberately provoke the workers into industrial action. Many of the manufacturers were members of the Anti-Corn-Law League (ACLL), and their motivation was that such strikes could bring down the government and lead to repeal of the Corn Laws. So, various factors came together to foment trouble at the cotton mills of South-East Lancashire in the summer of 1842.

The first General Strike

This year would witness the first General Strike in British history, and Stalybridge would be at the epicentre of much of the trouble associated with the strike. Furthermore, the contention that the manufacturers were involved in causing the turn-outs is supported by the fact that the initial strike in Stalybridge was at the Bayley Bros. cotton mill. In order to maintain pressure on the Government, the ACLL required plenty of money. Over the years from 1838 to 1846, the ACLL launched a series of appeals, the first in 1842/3 for £50,000, the next in 1844 for £100,000 and the last in 1845 for £250,000. A history of the ACLL (Prentice, 1853) reveals a £400 contribution from Stalybridge to the first, a £300 contribution from William Bayley Bros to the second, and a £1,000 contribution by Bailey Bros. of Stalybridge to the third fund-raiser. The heavy financial contributions by this firm to the ACLL cause and the fact that the company’s workers were the first to strike, and most militant, is certainly very suggestive of the mill-owners complicity in the dispute.

The strike had begun in the Midlands’ coalfields but soon spread to the great industrial centres of the north in Lancashire, Yorkshire and Scotland. And it was the Bayley’s cotton mill in Stalybridge that was the first in the area to be closed by the strike. This town was also the source of some of the most radical strikers. Associated with the withdrawal of labour was a certain amount of violence and turbulence. Not all mills in the Manchester area stopped working immediately, and this led to groups of strikers travelling around the district trying to persuade all mill workers to come out on strike – using whatever level of force was ‘necessary’. One tactic of the militant strikers was to remove the plugs from the boilers of the steam engines powering the mills, leading to the unrest being labelled the ‘Plug Plot Riots’.

The Manchester Times & Gazette of 13th August 1842 reported that at about four o’clock on the afternoon of Monday the 8th August “…a mob of four or five thousand persons consisting of part of the turn-out spinners and weavers of Ashton and Stalybridge entered this town [Oldham] by the Ashton-under-Lyne road. They appeared to be mostly young men,… a number were armed with bludgeons, sticks, &c. On reaching the mills of Messrs Lees, Milne &c., at Primrose Bank, they demanded that the workpeople should cease working.”. It appears the mob was successful in stopping the work at numerous mills in Oldham; although, at some mills they were prevented from entering by a combination of mill managers, owners and local police officers. In the following week the newspaper recorded the occurrence of numerous meetings of operatives and local businessmen on Curzon Ground, Greenacres Moor and Oldham Edge with much discussion of both recent wage cuts and the implementation of the People’s Charter. Things got so heated that the authorities called up the military. On Wednesday the 17th August 30 dragoons, 30 artillery men with a six-pounder canon and two companies of the 48th Foot arrived in the town. Nevertheless by Saturday, the Manchester Times was reporting that “Oldham and adjacent districts are in an orderly state, and there is no appearance of riot, although all the mills and collieries are stopped.”.

Clearly the strike brought much hardship to the operatives, the newspaper reporting that there were gatherings of women (operatives wives and relatives) on the Town Hall steps demanding relief from the charities committee – apparently to no avail. Indeed, there are several accounts of operatives and their families coming close to starvation (see Vallance, 2009 and Butterworth, 1856). As a result, over the following weeks the workers in Oldham slowly returned to work, by the 23rd August all the hat manufactories and the two machine-making mills (Hibbert & Platt and Asa Lees) had started up again, and all but 12 cotton mills were back at work. By the following Monday (30th) all but six mills had recommenced working, but that same day there was much excitement in the town that agitators from Stalybridge were about to return to try to persuade the operatives to strike again. The Times reported that “…a body of Ashton turn-outs was on its way to stop the mills. Persons, however, were stationed on top of the church steeple to give due notice…a considerable number of individuals were perceived to be holding a meeting on Brown Edge, a hill near Mossley… but happily, for the peace of the town, the Ashton turn-outs didn’t visit the place.”. Clearly, the strike in Oldham was almost ended, although that same day a “…working man named Robert Taylor, an iron turner, was taken into custody during the day for drawing an engine plug.”.

South-East Lancashire and North-East Cheshire were at the heart of the General Strike of 1842 with over a 100 cotton mills shut-down and about 50,000 operatives turned out; however, by Saturday the 10th September the Manchester Times was reporting that, in Oldham, all the mills and collieries were fully at work. Weavers in Manchester held out for another few weeks, but ultimately the turn-out lasted barely a month. However, for comparison, the 1926 General Strike lasted only nine days. Nevertheless, at its height the 1926 strike involved almost 2 million workers compared with only half-million who turned-out in 1842. In 1926 the UK had a population of about 43 million with around 19 million in the work-force (Lindsay, 2003); so, 2 million on strike represented 10% of the workforce; if we assume the work-force in 1842 was a similar proportion of the total population (44% of 27 million, or 12 million), then 0.5 million would have been about 4% of the work-force on strike.

Daniel’s family

Despite the benign nature of the Ashton brothers as employers, I suspect that Daniel Thomas would have been forced to stop work during the strike. It should also be noted that the Ashtons, like the Bayleys, were major contributors to the ACLL (various members of the family donating almost £5000 to the fund-raisers in 1844 and 1845), and so were perhaps privately hoping that the strikes might put pressure on the Government to repeal the Corn Laws, as well as implement the People’s Charter.

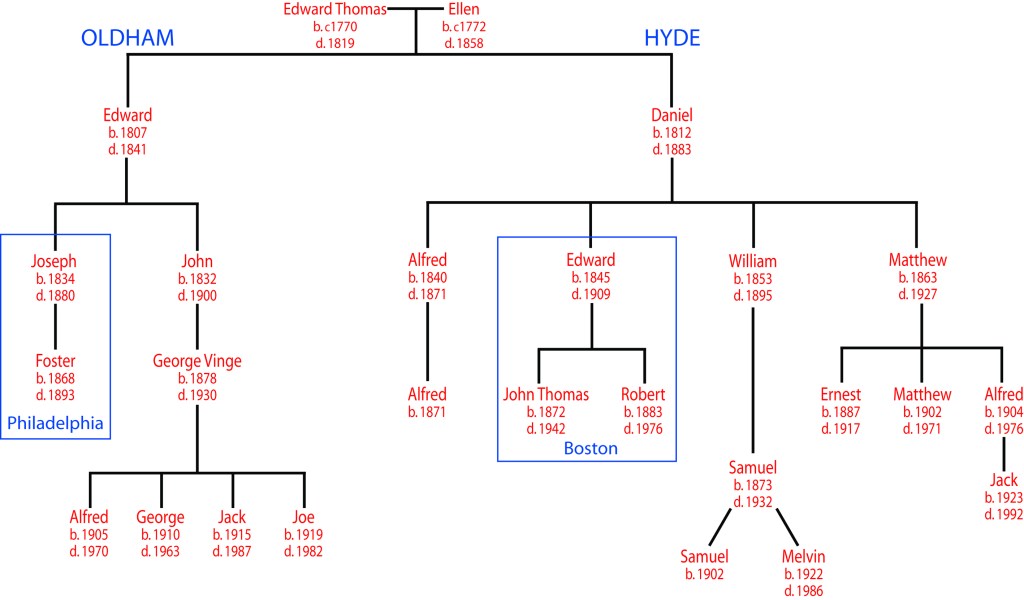

Following this industrial dispute, Daniel would continue working in the cardroom of the mill into his sixties, variously employed as a carder, grinder (responsible for maintaining the carding machine), or overlooker. Ultimately, Daniel and Jane would have 8 children, of which I discovered at least four sons, Alfred (b. 1840), Edward (b. 1845), William (b. 1853) and Matthew (b. 1863) who married and had large families in the Hyde, Denton, Dukinfield area (see family tree at the end of this chapter).

Daniel’s eldest son Alfred was killed, just 30 years old, in a tragic accident at the Daisyfield Colliery in Newton (Hyde; no. 2 on map above). It seems that little before 5.30 pm on the evening of the 27th February 1871, Alfred turned up for his night-shift driving the colliery engine used to lift the cage that transported workers to and from the pit-face. At the inquest into his death, one of his fellow workers said that Alfred appeared a little worse-for-wear from alcohol when he arrived for work, but that he seemed fit enough to carry out his duties. Nevertheless, around 7.20 in the evening Alfred told one of the miners that he had got the cage stuck by winding it too far. In order to free the cage he climbed up onto the cage to attend to the mechanism, but the cage shifted under his weight and he slipped and fell down the shaft – about 330 ft – to his death. One of his work-mates testified that Alfred hadn’t previously arrived for work drunk, so it’s surprising that he left home on a Monday afternoon with the intention of drinking heavily before he had to work a nightshift. At the time of his death, his wife Alice was pregnant with their fifth child – also Alfred. This Alfred Jr. would later marry and have a daughter, Alice, but I’ve found no sons of his marriage. Alfred Sr.’s wife, Alice, had five more children after her husband’s death, but never remarried, and there is no indication of who the father of these children was. Only one of these children survived childhood, a boy named Joseph Edward Thomas (b. 1875). This Joseph would marry and have four sons with the surname Thomas, but none, of course, descendant’s of Edward and Ellen.

Another of Daniel’s sons, Edward, emigrated to the U.S.A. taking two sons (John Thomas and Robert) with him. Edward’s son Robert appears in the 1940 U.S. census with his wife Edna, and three children, Roberta (b. 1925), Robert (b. 1928) and Raymond (b. 1932); so, it’s likely that there is a branch of the Thomas family now in New England.

Both of Daniel’s other sons, William and Matthew were coalminers. In 1881 the family (including Daniel, William and Matthew) are living in Coal Pit Square, Hyde. Coal Pit Square is close to Spring Gardens and the Bayleyfield Coal Pit (no. 3 on map above) where the brothers may have worked. However, neither is their home far from the Daisyfield Pit where Alfred had died, nor the Hyde Lane Pit (no. 4 on map) close to Hyde Station. The large number of coal pits in Hyde makes it difficult to know where William and Matthew worked, but in 1891 William is living in Edward Street (no. 5 on map) just across Manchester Road from the Hyde Lane Pit; so it’s possible that William was working at this colliery at the time of one of the worst mining disasters in the area. On the 18th January 1889 twenty three men were killed and five others seriously injured by an explosion of firedamp (methane). Most of the men were not victims of the explosion itself, but were asphyxiated by the resulting ‘afterdamp’ (mainly carbon monoxide). Over 200 men were employed at the colliery, but the morning shift, during which the explosion occurred, consisted of 43 men and boys with another 30 individuals due to work the afternoon shift. The inquest listed the dead and 14 of the 21 survivors. William and Matthew were not amongst the dead or named in the list of survivors, so whether Matthew had already moved to Dukinfield, or whether either of them was amongst the unnamed survivors, or worked a different shift that day I cannot say.

Of the five grandsons of Daniel who remained in the Hyde area I’ve only found the marriages of three (Alfred’s son Alfred, b. 1871, William’s son Samuel, b. 1874, and Matthew’s son Alfred, b. 1904). Alfred (son of Alfred) as I’ve mentioned above had a daughter, Alice. Samuel had two sons from two different marriages, Samuel (b. 1902) and Melvin (b. 1922); however, I’ve not discovered whether either son married or had children. Matthew’s eldest son Ernest was killed in the Great War while still unmarried. I’ve not found a marriage for his second son, Matthew, but his youngest, Alfred, had a son called Jack born in 1923 who was still single in 1939. So, it’s possible that Jack, Samuel (b. 1902) or Melvin had sons to carry on the Thomas name in the Hyde/Dukinfield area of Greater Manchester.

Following the 1851 census date, the next notable piece of information I’ve discovered is the record of Ellen Thomas’s death on the 26th May 1858. Ellen died in the Union workhouse in Stockport of ‘old age’ – she would have been in her 86th year. The record of her death states that she was the widow of Edward Thomas, wheelwright, but still no indication of where Edward was from – chances are he was also from the Wrexham area. So, for now, the trail of the Welsh Thomases grows cold and I must return to the Oldham branch of the Thomas family.

Oldham Thomases

As we’ve already seen in Chapter 1, Daniel’s brother Edward married Elizabeth Dalton in Oldham parish church in 1829, and the couple would have four children: John (b. 1832), Joseph (b. 1834), Fanny (b. 1836) and Edward (b. 1839). Both Fanny and Edward died in infancy, but John and Joseph would survive into adulthood.

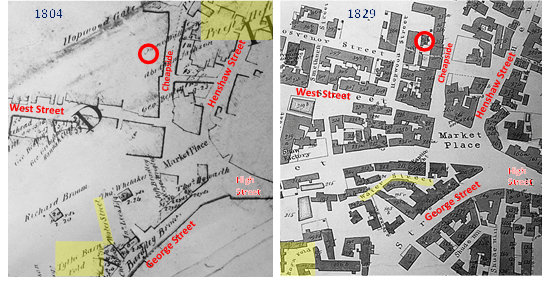

At the time of their marriage Edward was living in Lord Street and Elizabeth in Priesthill. I believe Priesthill describes an area in the town centre that covers several streets, including a street that was later referred to as Cheapside. Indeed, it is most likely that Elizabeth would have been living at the Gardener’s Arms (circled on Dunn’s map, below), the pub run by her father from 1824 to 1838 (see Chapter 1). The Gardener’s was a substantial building covering almost a thousand square feet. According to Rob Magee, in a report of 1894 it was stated that the pub (then called the Museum Inn) had “…ten drinking rooms, three bedrooms and no bathroom,…accommodation for travellers…an enclosed yard but no stabling.”. On the other hand, it’s likely that Edward was living in some kind of small cottage or tenement. After their marriage the couple appear to have lived with Elizabeth’s father until at least 1837 in Cheapside – their address when their first three children were baptized. In 1840 when their fourth child, Edward, died they had moved to Morgan Square, and in 1841 their address was given as Barnfold, and later that year when Edward Sr. died his address is given as Water Street. These last three locations are all very close together south of Manchester Street, lying between George Street and King Street. Examination of the Ordnance Survey map of 1891 shows a maze of streets, courts, and squares in this region, raising the possibility that these three different locations actually refer to a single house described slightly differently in the various documents.

A later photograph of Water Street (c. 1880; below), appears to show a mixture of industrial buildings, tenements and small terraced houses. Unless fortunate to work for an employer such as Thomas Ashton (see above), many working people, at this time (1830s, 40s) lived in poor quality housing. Working-people’s housing varied from the very basic ‘cellar-housing’, somewhat better ‘back-to-back’ terraces and, for the better-paid, artisan workers, so-called ‘through terraces’ (for discussion see Olusoga & Backe-Hansen, 2020; and Chapter 5).

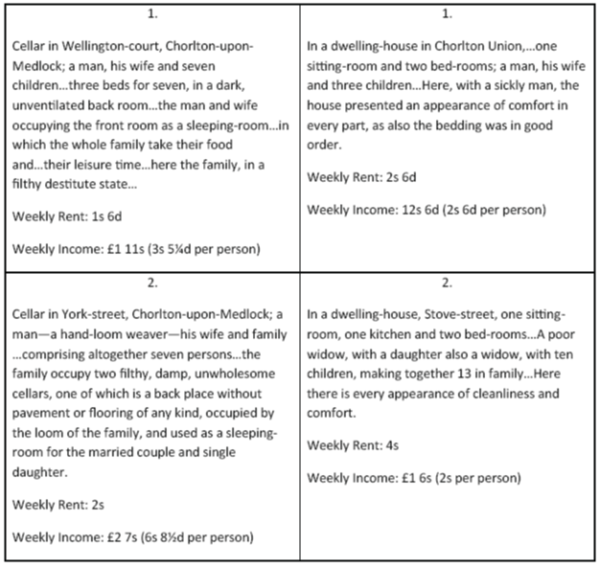

Cellars were occupied by the very poorest of workers in the towns and cities of the North. Such dwellings often consisted of a single room, inevitably dark and damp because of its location below street level. In Mary Barton Elizabeth Gaskell presents two versions of such housing: The first occupied by a single, employed woman with no family described as “…the perfection of cleanliness: in one corner stood the modest looking bed, with a check curtain at the head…The floor was bricked, and scrupulously clean,…”; in contrast, the second was occupied by a family brought destitute because of unemployment “…the cellar in which a family of human beings lived. It was dark inside…to see three or four little children rolling on the damp, nay wet, brick floor, through which the stagnant, filthy moisture of the street oozed up; the fire-place was empty and black…”. In a similar vein Edwin Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population (1842) contrasted families living in cellars (left) with those in houses (right; probably back-to-backs) in Manchester, thus:

I can only hope that Edward and Elizabeth remained usefully employed and were able to afford to live above ground in a property with more than one room. At the very least, the couple and their two sons might have lived in two rooms: a kitchen-cum-living room and a single bedroom in either a tenement or a back-to-back house. I doubt that their accommodation would have been as desirable as that provided to the Hyde Thomases by the Ashton family, or even a through-terrace as occupied by their son, John, and his family in later years (see Chapter 5).

Like Daniel, Edward was employed in the cotton industry described on various documents as a spinner, weaver or rover. A rover was employed in the cardroom running a machine that splits and aligns the cotton fibres coming out of the carding machine before the fibres are twisted into thread. However, in the record of his burial he was described as a gardener. The cause of his death was recorded as asthma. Considering his original occupation his asthma may have been a direct result of inhalation of cotton fibres, or byssinosis. It’s possible that because of this lung disease Edward had to quit working in the mill and found a job tending gardens. Edward would die when only 34 years of age, and the two boys were just nine and seven. Just six years later the boys’ mother would also pass away leaving John and Joseph orphans at only 15 and 13 years of age, respectively. At the time of her death, Elizabeth and the boys were living in Soho Street at the bottom of Greenacres Road (opposite Hope Chapel). As I’ve noted at the end of Chapter 1, the boys would be taken in by Elizabeth’s sister, the boys’ aunt Sally. I will return to John’s and Joseph’s stories in future chapters, but next I will make a little digression into the ancestry of John’s future wife, Sarah.