“We the free People of England, to whom God hath given hearts, means and opportunity …Agree to ascertain our Government, to abolish all arbitrary Power, and to set bounds and limits both to our Supreme, and all Subordinate Authority, and remove all known Grievances.” — Lilburne, Walwyn, Prince & Overton, An Agreement of the free people of England, 1649.

I began my investigations into my family history with the simple aim of discovering more about my paternal great grandfather, George Thomas, who was something of an enigma – lots of stories, but no written or photographic records as to who he was. I started by looking for the record of his death on the newly-launched web-site 1837online (now findmypast). I knew that he had died before my father was born (1931), but after my grandfather’s youngest brother, Joe, had been born (1919). Even by limiting my search to deaths in this period, and in Oldham, this was not an inconsiderable task; George Thomas being quite a common name. (Note: In the early days of 1837online you had to manually search each quarter year separately.) However, I was given a major clue by my dad’s cousin Lena, who told my dad that their grandfather’s middle name was very unusual. His name was George Vinge Thomas. Fortunately, the death registers list the middle initial, and so my job was made that much easier knowing that I just needed to find a George V. Thomas. I finally found George’s death in August 1930, just 5 months before my dad’s birth.

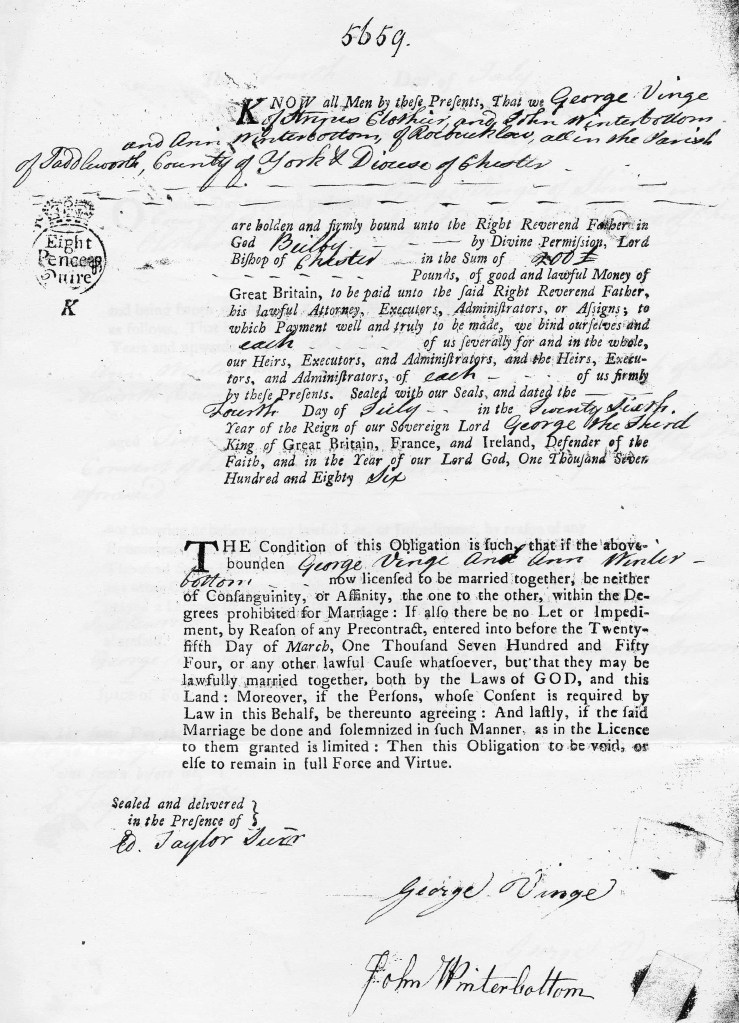

Still, where did this strange middle name come from? It turned out to be his mother’s maiden name. In 1855 George’s father John Thomas married Sarah Vinge at Prestwich Parish church. My search through the census records of 1841 to 1861 revealed that there were only two families, and a single woman, by the name of Vinge in Oldham. The heads of these two families, George and John, and the single woman, Mary, were all siblings, and there wasn’t another Vinge within a 100 miles of Oldham. It turned out that the Vinges of Oldham all descended from a George Vinge who married an Ann Winterbottom at St Chad’s, Uppermill in 1786. Fascinatingly, this marriage was not by banns, as are most marriages, but by licence. This was more commonly used by the better-off in order to keep the marriage out of the public eye. Marriage by licence required someone to promise to pay a bond if the marriage were proven to be illegal (e.g., if either the bride or groom was already married), this meant that it was rarely used by working people. In 1786, the bond (see below) amounted to £200, over £15,000 in today’s money. However, I wonder if this type of marriage was also forced upon Dissenters? The Marriage Act of 1753 stated that all (except Quakers and Jews) had to be married in the Anglican church; thus when the bride was a Non-Conformist (or Roman Catholic), the reading of the banns would not be possible, as the bride would not be a parishioner; thus, the marriage might have to be carried out by licence.

The Winterbottoms

The record of Ann’s christening at Greenacres Independent Chapel is accompanied by the record of all her siblings’ baptisms on the very first page of all the baptismal records. Indeed, the first page of the records lists the children of three Winterbottom families: Those of John and Sarah of Roebuck Low (Ann’s parents), the children of Robert and Sarah of Green lane, and those of Henry and Alice of Gibraltar (street?). This would suggest Ann’s parents, and other, perhaps related, Winterbottoms, played an integral part in the running of the church, and were probably ardent Dissenters.

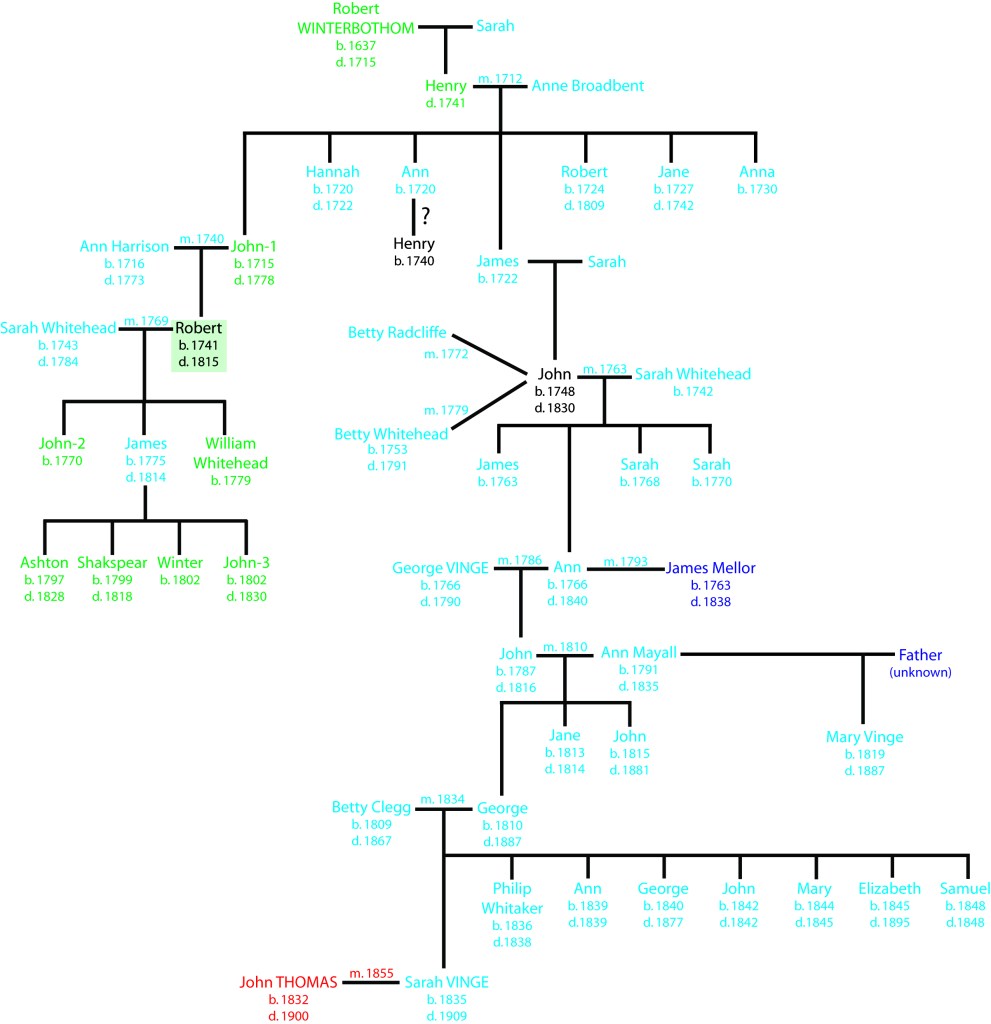

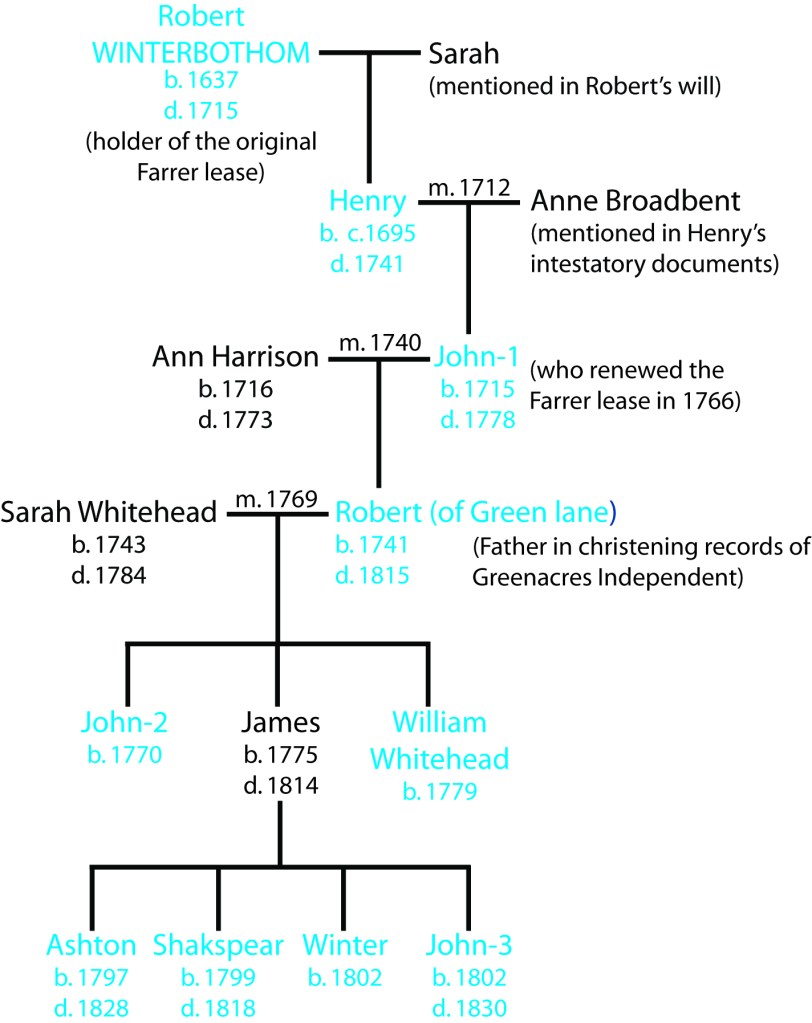

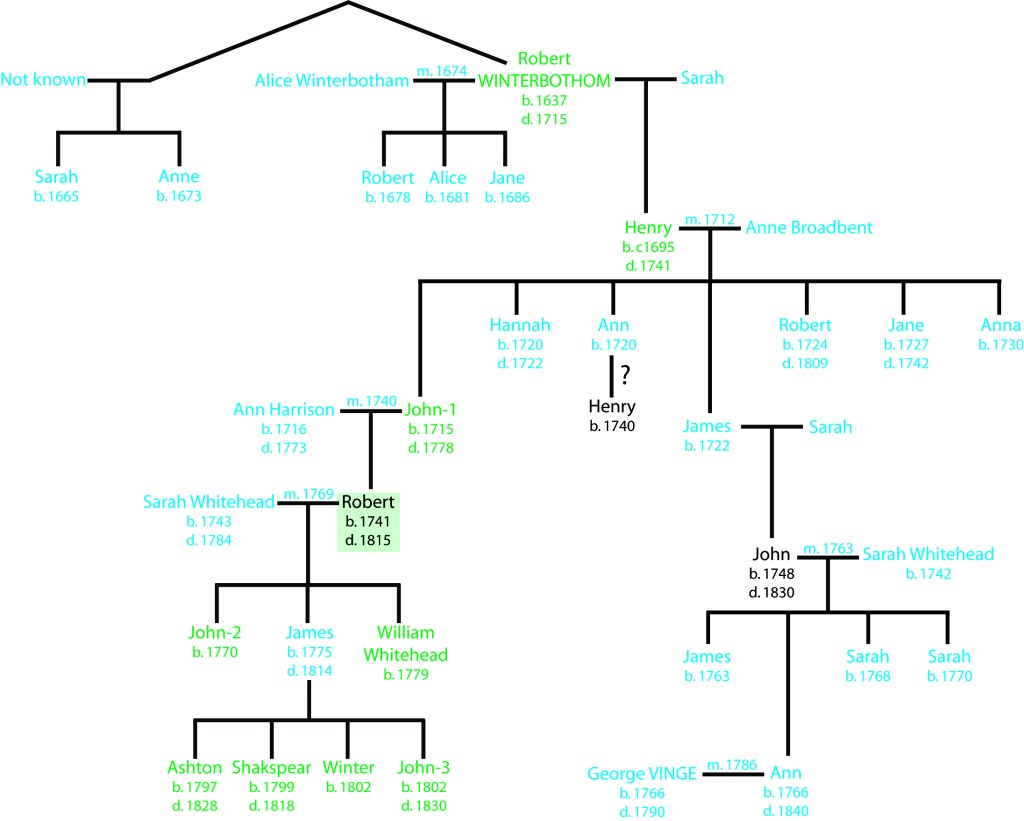

Trying to decipher the relationships between the numerous Winterbottoms in Saddleworth, and even in the small area of Strinesdale, is very difficult. At the end of this chapter I’ve outlined a family tree that I think best fits with the records and documents that I have discovered over the last 10 years or so. The first document of note is the will of one Robert Winterbothom of Strynds in 1714/15 (see Appendix 4). The beneficiary of this will is Robert’s “…yonger Sonn Henry Winterbothom…”, and a major part of the inheritance was “…One Indenture of Lease of James ffarrer Esq…”. James Farrer was the Lord of the Manor of Saddleworth who rented out many farmsteads in the area, he would die in 1717, but the lordship would pass eventually to his cousin, another James Farrer of Barnburgh. Robert’s will also mentions his wife, Sarah, and ‘six children’, one of whom Alice was witness to the proving of the will in 1716. I’ve found a christening of Alice daughter of Robert and Alice at St. Chad’s in 1681, as well as two other children from this marriage. I’ve also found baptisms of a Sarah (1665) and an Anne (1673) whose father was Robert and an un-named mother (note: Robert and Alice were married in 1674; see tree below). Along with Henry (son of Robert’s third wife, Sarah), this would make six children as mentioned in Robert’s will. However, I’ve not been able to locate a baptismal record for Henry or a marriage of Robert to Sarah – probably due to the patchy nature of the registers in the period before 1720. I can only assume that, despite the fact that he was the youngest of the children, Henry inherited because the children from the earlier marriages had moved on, and that the occupants of the farmstead were then Robert’s third wife, Sarah, and Henry (her son?).

In 1741 Henry Winterbottom of Strines died intestate, but the intestatory documents (see Appendix 5) reveal that the administrator was Henry’s son, John Winterbottom (see Obligation). Also mentioned in the documents is Henry’s wife, Anne. Further investigations revealed the marriage of a Henry Winterbottom and an Anne Broadbent at St Chad’s in February 1712. This couple had five children baptized at Saddleworth parish church between 1720 and 1730, including a James (Ann’s grandfather?), but no John. In the transcribed registers of St Chad’s, Saddleworth, the record of John’s marriage is accompanied by a footnote saying that John “…died of palsy, 27th July 1778, in his 64th year;…”, this would imply he was born in 1715. Unfortunately the records of christenings at St Chad’s from the middle of February 1705 to March 1715 have been lost, and there is no record of John’s baptism from March to the end of 1715. It’s possible that the record of this John’s christening is amongst those that have been lost from the St Chad’s registers.

There is a will of a John Winterbottom (1770; see Appendix 9) who died in 1778 and left the leasehold of a property in Strines (rented from James Farrer) to his son Robert, and names his brother James as one of the Executors of his will. My best guess is that John, son of Henry and Anne, who is mentioned in the intestatory documents is this John who died in 1778, and that he is the brother of James who may be the father of John who was the father of Ann Winterbottom who married George Vinge in 1786.

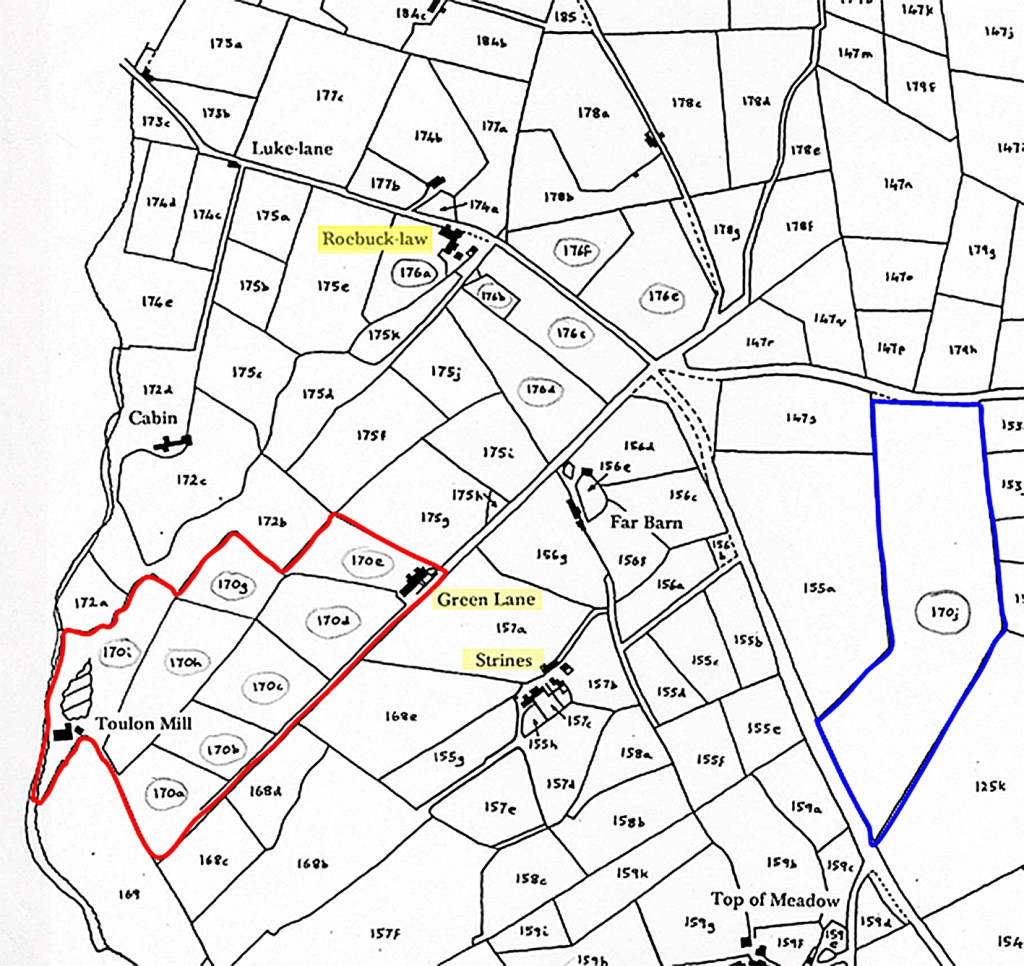

In 1766 John Winterbottom of Strinds renewed the lease on the farmstead for a further 150 years, at a rent of £9 and 9s (nine guineas) per annum (see Appendix 6), and the records of James Farrer in 1770 reveal that a John Winterbottom is the renter of a farmstead of 14 acres in Strines (area outlined in red on the tithe map, above).

I believe this John Winterbottom is the father of the Robert named in the baptismal records of Greenacres Independent Chapel (i.e., Robert of Green Lane). This thesis is supported by the fact that as stated above a John Winterbtoom left the leasehold of a farmstead in Strines to his son Robert when he died in 1778. Also, the fields listed in John’s 1766 lease are referred to in Robert’s will of 1815 (see Appendix 7) suggesting that Robert inherited these fields from his father, John. Together with a deed of 1801 (see Appendix 8), Robert’s will divides the farmstead and Toulon Mill (see tithe map above) amongst his two sons, John-2 (see tree below) and William Whitehead, and four grandsons – Ashton, Shakspear, Winter and John-3. Finally in the Higson papers (1900-30) it is stated that this farmstead is owned in 1822 by John Winterbottom. However, the 1801 deed shows that John-2 only obtained a third share in the mill (Toulon, aka Holes), and the 1815 will reveals that John-2 was the Testator (or Executor), but was not a beneficiary. The majority of the property was left to Robert’s younger son, William Whitehead Winterbottom, and his grandsons. It’s possible that the John mentioned in the tithe records (and by the Higsons) is taken from the original Indenture of lease that is in the name of John-1 (see Appendix 6). My interpretation of all these data are that the lease originally taken out by Robert (d. 1715) has passed down through Henry, John-1, Robert to William Whitehead and Robert’s grandsons, giving rise to the following minimal family tree tracing the progression of the Green Lane farmstead through the Winterbottom family:

Considering the juxtaposition of the records of the baptisms of Robert’s children with those of Ann’s father John, and the location of their homes (Green Lane and Roebuck Low being about half-a-mile apart; see tithe map above), I believe it likely that John and Robert were related. But how?

In the records of Saddleworth Parish Church (St. Chad’s), in addition to the formal records, are numerous footnotes that were added by the editor, John Radcliffe (1887-91), many based on the research of the Rev. Raines (1828-78). Included in these footnotes are several pertinent to the Winterbottoms of Strinesdale. In particular, in the record of Ann’s father’s baptism it states that his parents were James (clothier) and Sarah of Delph-Greaves with a footnote that “John Winterbottom of Strines, died 28 January, 1830, in his 82nd year; and Betty, his wife, died 7th June, 1791, in her 38th year” (note: this would have been his third wife Betty Buckley, née Whitehead, not Ann’s mother). John is also referred to as “…of Roebucklow” in these records. As stated above I think that John’s father James is the brother of Robert’s father John-1 (see trees,above and below). This would make John of Roebuck Low and Robert of Green Lane cousins. As to Henry of Gibraltar who also appears in the baptismal records, his relationship to the other two Winterbottoms is not clear. I’ve speculated that he may also be a cousin by an illegitimate birth to one of John’s and Robert’s aunts. An Ann Winterbottom, possibly the sister of John and James, baptized a son called Henry at Oldham Parish church in 1740, the father being named as Henry Holme, a resident of Oldham workhouse. This give rise to the following tree that shows the renters/owners of the Green Lane farmstead in green, and the father’s in the Greenacres Independent baptismal records in black:

A family of ‘little makers’

Also living at Strines, close to Roebuck Low and Green lane, was John’s daughter’s husband, George Vinge. Each of these three homesteads are in Saddleworth in the area now referred to as Strinsedale (see tithe map, above). According to George’s marriage allegation and bond, both Ann’s father and George Vinge were ‘clothiers’ involved in the woollen industry; likewise, the christening records show that Robert Winterbottom was also a clothier. In many ways Strinesdale is a place where two cultures come together, notwithstanding the historic rivalry between the two counties, we can also see here the different business practices referred to in the first chapter. Oldham, increasingly dominated by the mill-owner with a multitude of employees, contrasting sharply with rural Saddleworth where the independent cloth-maker/merchants such as John and Robert Winterbottom and George Vinge were the norm. E.P. Thompson (1963) describes the master-clothiers as ‘kulaks’ (wealthy, independent peasant farmers), and according to the Cleckheaton Guardian – “The ‘little makers’…were men who doffed their caps to no one, and recognized no right in either squire or parson to question, or meddle with them…” – which further suggests that the Yorkshire reputation for bluntness can be traced back to these independent cloth merchants.

The Winterbottom families of Strinesdale were probably reasonably well-off. In his History of Oldham (1817), James Butterworth states that Greenacres Independent Chapel (the one opened in 1785) contained a vault with a memorial inscription to a Mr. Winterbottom of Green lane (probably the Robert named above who died in 1815). Furthermore, Nightingale (1893) relates that some time before 1775 the new minister of Greenacres Congregational Church, the Rev. Edward Harrison from Swinden-in-Craven, was introduced to the congregation by “Mr. John Winterbottom, of Green lane, a woollen manufacturer, who frequently went to Craven on business matters”. There is also a deed from December 1770 that records an agreement between Abraham Lees (yeoman of Roebuck Low) and John Winterbottom (clothier of Strines) to divert water from a weir at Rovingshead in a drain down Green Lane to John Winterbottom’s dyehouse, and “…to make a pond & erect a turfcoat, dye house, wash houses, etc. on a parcel on N side Green Lane…”. I believe this John Winterbottom is Robert’s father (see John-1 in tree, above). In the tithe map (above), at the far west end of Green lane, can be seen Toulon Mill lying just north of the lane. This mill is not the dyehouse built by John, but one erected by his son Robert (c. 1800); however, probably on the same site.

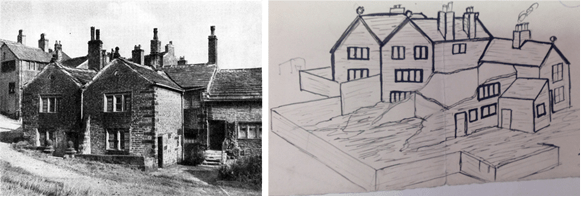

In the late 1600s the properties at Strines would possibly have been similar to the weaver’s cottage described in Chapter 1, but later in the mid 18th century these cottages would have been replaced by more substantial stone buildings. We can get some impression of these structures from buildings still standing in Saddleworth and sketches made by Charles Higson of what was left of the Roebuck Low homestead in 1905 (see above). In sale documents of the Roebuck Low property recorded by the Higsons there is a statement “…compact and capable of being made into 3 Tenements for the occupation of Clothiers, if chose to be so occupy’d.”. In 1786 we know that the clothier John Winterbottom was resident here. In a will of James Lees in 1794 it states that the property is occupied by three tenants (Thomas Winterbottom, Robert Winterbottom and James Wilde). Clearly the homestead could well be described as a tenement divided into individual homes for several different families – something of a halfway house between the individual cottages of earlier times and the terraced housing that would come to dominate Oldham a century later in the Victorian era. My simple interpretation is that the buildings at these Strinesdale homesteads housed not only the families that farmed the surrounding fields, but also a number of clothiers such as John Winterbottom and George Vinge who purchased wool, and turned the wool into finished cloth, and then sold the cloth to various clothes manufacturers. Indeed, it’s possible that John, the clothier, even used the wool provided by his cousin Robert’s sheep.

The illustrations on the right give an idea of how the interior of these clothiers’ homes may have looked. In contrast to the weavers’ cottages described in Chapter 1, these dwellings have well-defined fireplaces with chimneys, and the floors are stone rather than earthen. The windows are leaded and much larger at this time, allowing in much more light; something that must have been particularly important for the cloth manufacturing process. Also shown in these sketches are the types of clothing worn in the late 18th and early 19th centuries by the manufacturing classes. In many ways these haven’t changed much from the clothing in the 17th century – the men still wearing breeches and long stockings, and the women in long skirts with aprons, and small wimples or bonnets holding in their hair (see Chapter 1). The wealthy clothiers perhaps differentiated from the labouring classes by their smart waistcoats, topcoats and better quality leather shoes.

Greenacres Independent and the religious fall-out from the Civil War

As mentioned above, the children of John Winterbottom were baptized at the Independent Chapel at Greenacres. In addition the children of his daughter Ann, and those of her Vinge descendants, were all baptized at the same church. We saw in the first chapter that this church had been founded by the ejected minister from Oldham, the Rev. Robert Constantine. The reverend seems to have been a person of very strong beliefs. Even before his final ejection from the Church, Constantine had once previously been removed from the curateship of Oldham Parish. He became vicar in 1647 just following the first Civil War and, as later events will support, we must assume he was a supporter of Parliament rather than the Monarchy.

During the Civil War period there were three factions on the Parliamentary side. The Presbyterians (including ministers of the Manchester Classis, of which Constantine was a member), the Independents (including soldiers of the New Model Army and radicals such as the Levellers), and the Grandees, such as Oliver Cromwell (represented locally by Sir Ralph Assheton of Middleton, a colonel-general in the Parliamentary army and MP for Lancashire in the Long Parliament). The Grandees generally held the middle ground between the more Puritan elements and the Independents and often espoused toleration, but held firm control of Parliament and at crucial periods actively suppressed the more radical Independent elements of the New Model Army. The clashes between the Grandees and Independents came to head when the Grandees decided to make considerable concessions to the Monarch in the constitutional settlement following the first Civil War. Indeed the disagreement was so severe that the Army forcibly removed some MPs who had voted for compromise with the monarch (including Sir Ralph Assheton). Known as Pride’s Purge (1648), the removal of almost half of the MPs converted the Long Parliament (with 471 members) to the Rump Parliament (240 members).

Whilst these squabbles amongst the Parliamentarians were going on, King Charles tried to make use of the disruptions by secretly negotiating with Scottish Covenanter’s to raise an army to defeat Parliament, and thus the second Civil War ensued. Ultimately, Parliament and the New Model Army were again victorious, and Charles was executed (1649). As a result, government of Britain changed from a Monarchy to a ‘Commonwealth’ presided over by Parliament, but in reality controlled by the Grandees. In order to enforce their control of Parliament, the Grandees demanded that both the soldiers and curates demonstrate their loyalty by swearing an oath of allegiance known as ‘The Engagement’.

Although, most disputes on the Parliamentary side had been between the Independents and the Grandees, it turned out that the main opposition to the Engagement came from the Presbyterians. These puritan elements viewed the Grandees as being too tolerant of both the Independents and the Episcopalians (former Royalists). Many Episcopalian sympathizers signed the Engagement even though they had no intention of complying with it, on the other hand the Presbyterians refused.

Constantine was a member of the Manchester Classis which was strongly Presbyterian and, in October 1650, he refused the Engagement and was vigorously prosecuted by a local Episcopalian, James Ashton of Chadderton (a Justice of the Peace, who was the son of a local Royalist – Edmund Ashton). As a result he was forced to leave his curacy in the parish (see Nightingale, 1893). Interestingly, following Constantine’s refusal of the Engagement the curate appointed in Constantine’s stead the Rev. John Lake, an Episcopalian and Royalist, was much disliked by the congregation (including Henry Wrigley, see Chapter 1) and just 4 years later was himself ousted by the congregation on the grounds that “…(he) hath been a grand cavalier in former tymes…to be an enemy to reformacon…to administer the (sacrament) in a general and promiscuous way…doth much countenance loose persons…(and) doth baptyse basthardes…” (see Nightingale, 1893). Despite his unpoplularity in Oldham, the Rev. Lake was much admired in the church and, following the Restoration (both of King and bishops), rose to the rank of Bishop, initially of Sodor and Man, then Bristol and finally Chichester.

In 1654 Constantine was reinstated and served the parish until his ejection in 1662 following the passing of the Act of Uniformity. This Act was swiftly followed by the Conventicle Act (1664) and the Five Mile Act (1665). The first of these Acts banned any meeting of five or more people for unauthorized worship, and the second forbade ejected ministers from coming within 5 miles of the previous churches of their employment. However 10 years later, in an effort to allow greater religious freedom, Charles II enacted the “Royal Declaration of Indulgence”. And although this was seen in many quarters as his attempt to relieve Catholics from persecution (both his wife and mother were Catholic), it also gave more freedom to Dissenting ministers. In 1672, the Rev. Constantine began preaching again in a thatched cottage in Greenacres less than 3 miles from Oldham parish church (despite the fact that the Five Mile Act wasn’t officially rescinded until 1812).

In 1673 Parliament, upset by the freedom afforded to Catholics by the Declaration, forced Charles to replace the Declaration of Indulgence with the Test Acts which demanded that anyone entering public office should deny the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. The repeal of the Declaration also made things more difficult for Non-Conformists, and it is thought that even though the Rev. Constantine continued to preach in Greenacres, he did so in secret. However, in 1687 James II proclaimed a new Declaration of Indulgence to remove legal restrictions on Catholics and Non-Conformists. Yet again, this was resisted by many in the Church of England, including ‘Seven Bishops’ who James charged with sedition, and imprisoned in the Tower of London – one of these bishops was one John Lake, Bishop of Chichester!

Ultimately, James would forfeit the throne in the “Glorious Revolution” to William and Mary. In 1689 Parliament would pass the Act of Toleration legalizing places of worship for Dissenters, and Greenacres Independent Chapel would become Oldham’s first Non-Conformist church. Ten years later, at the time of Constantine’s death, the Independent’s congregation had grown to such an extent that a large farmhouse and barn had been converted to a permanent place of worship; however, just 16 years later this makeshift chapel was almost completely destroyed by rioting Jacobites (Bateson, 1949).

The accession of George I following the death of Queen Anne was not universally popular (‘a German imported from Hanover’), and reawakened the idea of restoring the Scottish Stuarts to the English throne. From 1710 through 1715 numerous riots (Sacheverell [1710], Coronation [1714], and Rebellion [1715]) took place across the country promoted by Tories, who hated King George, and who had been effectively side-lined in Parliament by the Whigs. The Tories were also Anglicans who fervently opposed Non-Conformism, and during the disturbances in the Manchester area in June of 1715 a gang of youths, after rampaging through Manchester, set out to Yorkshire passing through Oldham. Here they sought out the nearest Non-Conformist meeting place (Greenacres Independent) and proceeded to demolish the building. Ultimately, the rioters were brought to book, and the parents and masters of the youths were made to pay compensation for the damage they had done (£1 for each parent/master). Presumably the parishioners were suitably recompensed, and the chapel returned to a usable state. Nevertheless, it would be another 70 years before the Independents opened their first purpose built chapel – described by Butterworth (1817) as a “…handsome edifice of stone, and will contain 500 people.” (see picture below). This was the chapel containing Robert Winterbottom’s vault; unfortunately, the vault appears to have been destroyed during demolition of the chapel in 1854, and his grave moved to the present churchyard.

Vinge family origins

Clearly, the Winterbottom family of Strinesdale were very influential in the church, and presumably ardent Dissenters, which may explain the marriage by licence of John’s daughter Ann. There is no record of a birth/christening of a Vinge in the months closely following the marriage that might be expected if Ann was pregnant when she got married; so, it doesn’t seem that the marriage was by licence to keep it secret. The big mystery is the origin of Mr. George Vinge?

On the tithe map (above), we can see the proximity of Roebuck Low, the place of residence of John Winterbottom shown on the marriage bond, and Strines, the place where George Vinge was living when he married Ann, but I can find no baptismal record for a George Vinge, indeed any Vinge, in the area before 1787. I can only assume that George was not a local, and came from many miles away. A search of the on-line parish registers (either at familysearch.org or findmypast.co.uk) revealed a number of Vinge families in Reading, Berkshire, going back to christenings of John (1634) and Marie (1636) children of a William and Marie Vinge at St Mary’s church. However, the only George I could find born at approximately the right time (1766, if George was 20 at the time of his marriage as stated on the Allegation) was one baptized on Christmas day 1768 in St Giles Church, Cripplegate, London. After some research I discovered that this George was the grandson of a Ralph Vinge, butcher of Reading, and so indeed related to the large number of Reading Vinges. Nevertheless, I was later to discover that this George died in 1773, and so couldn’t have been the George that married Ann Winterbottom in Saddleworth in 1786. The only other clue I could obtain about George’s origins is a record of the burial of a John, son of John Ving in Blackburn in 1794. Whether this John Ving and George Vinge were related is a matter for further research.

On the web there is speculation that the name Vinge is a corruption of the French Vigne, and that the Vinges were French Huguenots who came to England following religious persecution in France. On the other hand, one interesting aspect to the historical entries relating to the Reading family (and the burial in Blackburn) is the use of the alternative spelling that lacks the final ‘e’. To me this suggests that the name was originally pronounced with a hard ‘g’, like wing rather than singe. This pronunciation is characteristic of the not uncommon Swedish name Vinge. Another argument against the Huguenot origin of the family is that the largest influx of Huguenots into England occurred in the late 1600s and, as stated above, there are clear records of the Vinges in Reading in the early 1600s. So, my guess is that the Vinges (or at least their surname) originated in Scandinavia not France. Whether the Oldham Vinges descend from an ancient Viking invader or a more recent Scandinavian immigrant is a mystery yet to be solved. George’s and Ann’s son John Vinge married Ann Mayall in 1810 at Manchester Cathedral (known at the time as the Collegiate Church). This sounds rather grand, but in reality was a cheap way of getting married. When getting married at the local church the couple would have to pay two fees, one to the vicar and one to the Collegiate Church; however, if they married in the Collegiate Church they only had to pay the one fee. As a result, marriage at Manchester Cathedral became very popular, and the minister of the church would hold mass marriages involving perhaps a dozen couples at a time! On the day that John Vinge was married, 9th July 1810, there were only 9 marriages; perhaps, a quiet day because it was a Monday.

John Vinge’s marriage was witnessed by a James Winterbottom, possibly his uncle, his mother Ann’s elder brother. As mentioned previously, deciphering the relationships of the many Winterbottoms in the area is not simple. The family tree at the end of the chapter is, therefore, somewhat speculative. I can be sure of Ann’s parents, and am reasonably confident that her father’s parents were a James and Sarah Winterbottom of Delph-Greaves; however, I have not been able to discover a marriage record for James and Sarah.

Food riots, Luddites and the Corn Laws

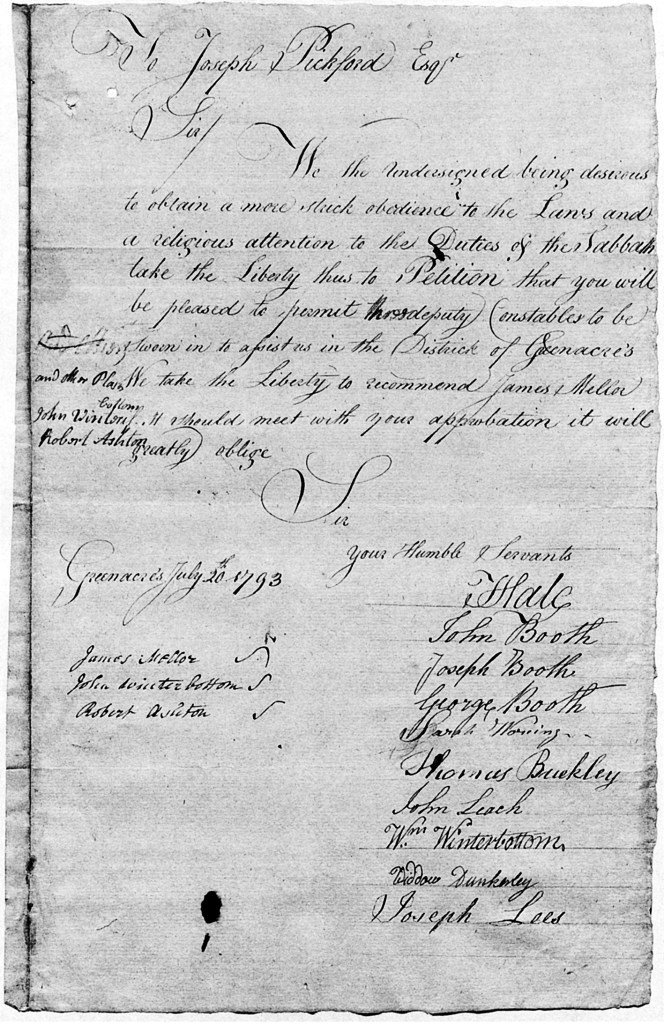

Returning to John Vinge, he is referred to as a weaver in the marriage record, this may reflect a step down from his father’s occupation of clothier or may just show a difference in names used for the same job in official documents. Nevertheless, he is still working in the predominant trade of the region – cloth-making. A trade in which his mother’s family had been involved for at least a hundred years. John would not have known his father who died in 1790 at the young age of 24 when John was just 3 years old. As we have seen in the previous chapters, John would have grown up in very turbulent times. We’ve seen how Oldham experienced a series of food riots throughout the 1790s and early 1800s, and the foothill regions of Greenacres and Saddleworth did not escape these tribulations. In Delph in July 1795 a crowd took all the loaves from a baker’s cart, but sold them at a reduced price, and then handed over the money to the baker. In Greenacres in 1793, the authorities were so worried that they drafted in extra deputy constables, one of whom was a John Winterbottom and another a James Mellor (see Petition, below). Following George Vinge’s death, John’s mother Ann would marry a James Mellor; so, it seems likely that these two new constables were John the son of Robert (Ann’s father’s cousin), and her second husband. This contention is further supported by the fact that a William Winterbottom was both a signatory to the petition and a witness of Ann’s marriage to James Mellor.

Other names on this petition of local interest are the signatories: John, Joseph and George Booth. According to Edwin Butterworth (1856), in the section on Greenacres: “The Booths were amongst the most ancient yeomanry families of the hamlet. George Booth was a holder of land in Oldham in 1735. The late John and Joseph Booth of Greenacres, yeomen, the former of whom died in 1812, and the latter in 1835, were partners with Messrs. Lees, Jones, and Co., the extensive colliery proprietors.” (see also: The Oldham Joneses…“). Another signatory, Joseph Lees could well have been one of the Booth’s partners in this coal-mining business.

The local magistrate to whom the petition was addressed was Joseph Pickford Esq. of Royton Hall. Of course, Royton Hall was the ancestral home of the Byrons. It was home of the Byrons from 1260 to 1662 when Richard, the 2nd Lord Byron, sold the Hall to the Standish family who in turn sold the Hall to Thomas Percival (a Crumpsall linen merchant). In 1763 Thomas’s great-granddaughter, Katherine, married Joseph Pickford of Althill, Ashton-under-Lyne, whose mother was Mary Radcliffe, sister of William Radcliffe of Milnsbridge. Just two years after this petition, Joseph Pickford would inherit the Milnsbridge and Marsden Moor estates from his maternal uncle. On William’s death Joseph assumed not only his uncle’s estates but also his surname, becoming Joseph Radcliffe; ultimately, Sir Joseph Radcliffe (Bart.), having been made a baronet in 1813 for his work as a magistrate during the Luddite riots of 1812.

In his history of Oldham, Edwin Butterworth (1856) gives an account of hand-loom weavers from Oldham travelling to Middleton to attempt to destroy power looms at a manufactory owned by Daniel Burton & Sons in April 1812. Apparently, the owners and management opened fire on the mob and two men from Oldham, Daniel Knott (20) and Joseph Jackson (16), as well as two others were killed. The next day the rioters returned to the mill and in a skirmish with the military another Oldhamer, John Johnson, was shot. In response, the militia in Oldham was called up for a fortnight and extra constables were sworn in. Such activity as this occurred across the industrial towns of England over the period from 1811 to 1817, and the participants have often been referred to as Luddites; although it is not clear whether these men were part of a greater organization by which all these disputes were co-ordinated.

As well as attempted machine breaking, Butterworth also mentions perhaps the more common occurrences of turn-outs (strikes) and lock-outs. A strike took place in the summer of 1815 in which almost all the cotton operatives in town turned-out to protest against a proposed decrease in wages; this strike seems to have been successful for the workers but this was probably an exception, the mill owners generally having the upper hand (see Chapters 1 & 4).

The effects on the working people of the employers’ attempts to reduce wages were compounded in 1815 by the passage of the Corn Laws. These laws were protectionist measures intended to reduce cheap imports of grain and maintain profits for British farmers. In doing so, these laws also increased the cost of flour, oatmeal and bread which were the staple foodstuffs of most working people. The repeal of these laws and the continuing lack of Parliametary representation for the occupants of industrial towns would become the main political issues of the next 15-30 years until the Great Reform Act of 1832, and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 (see Chapters 1 & 4).

From wool to cotton

Just as George Vinge died young so did his son John, at just 28 years of age when his eldest son, George, was barely five. John’s children were all christened at Greenacres Independent Chapel, and the family’s address is recorded as ‘Crowe’. Later census returns show George’s family living in ‘Crow’, a location close to the present Carrion Crow public house on Huddersfield road. The move of the family from Saddleworth to Oldham also seems to coincide with a switch from woollen cloth manufacturing to the cotton industry. In the 1841 and 1851 censuses George is described as a cotton-waste dealer. This change in industrial allegiance is not too surprising considering that the number of cotton mills in Oldham had increased from 31 in 1821 to 94 in 1840.

In light of our present-day obsession with recycling, George’s occupation seems to be way ahead of its time. The recycling of cotton waste (loose staple, unspun rovings and spun thread) for use in condenser spinning appears to have been an Oldham speciality. In 1841, 50 of the town’s 201 cotton firms (note: there were about a hundred mills; so, many firms would have shared the same premises) were involved in the spinning of cotton waste, this compares with 7 of 108 in Manchester, 1 of 93 in Ashton and none of the 170 firms in the neighbouring towns of Rochdale and Bury (Sykes, 1980). In Baines’s 1825 directory of Lancashire there are 8 cotton waste dealers listed in Oldham, by the publication of Slater’s directory of the county in 1846 this number had grown to 72, and in 1853 Whellan’s directory of Manchester and its environs lists 146 cotton waste dealers in Oldham; including the firm of Lord & Warburton of Fold Leech Mill, Greenacres Moor. In the same directory, the company partners are listed as William Lord and William Warburton both of Shaw. Interestingly, the banns of Sarah Vinge’s marriage to John Thomas record that Sarah is living at “Wm. Lord’s house, 25 Hope Chapel, Bellfield”. In today’s Oldham, Hope street and Bell street are both found close to Bottom o’ th’ Moor, just west of Shaw Road which, at the time of the marriage, was known as Fowl Leach. I think we must assume that her father was an employee of Lord & Warburton at Fold Leech Mill.

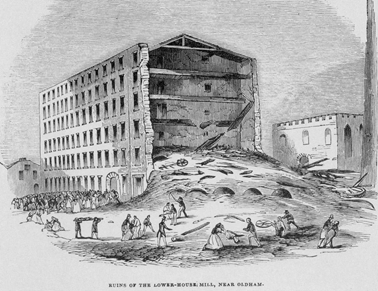

The same banns reveal that Sarah herself was a weaver employed by Radcliffe’s, and not far from Bottom o’ th’ Moor was Lowerhouse Mill (on what is now Barry street) which was owned by Samuel Radcliffe. The simplest interpretation is that Sarah worked at Lowerhouse Mill, a mill that just 11 years before her marriage had experienced a disaster that had been the subject of a Royal Commission. In 1844 an extension was being added to the existing mill (built 1821-4) when a ceiling beam gave way and the whole of the extension collapsed killing 20 people (see picture above). Three of the individuals killed were from the same family. The Illustrated London News reported that “Mary Tweedale… stated that one of the bodies lying at her house was that of her husband [Joseph, overlooker]; he was forty-four years of age. Another body…that of…Robert Tweedale, her son, aged seventeen years, a twister-in; and the third body…that of James…a younger son…aged twelve years…a reacher-in. The poor woman sobbed, and was quite overcome.” A later reading of the Royal Commission concluded that the high number of fatalities could be explained by the Victorian mill-owners’ practice of putting people to work in the lower floors of their factories as soon as they were habitable, while construction proceeded above (Swailes, 2003).

In the 1851 census while living with his aunt and uncle, John Thomas is described as working as a piecer in a cotton mill but, just 4 years later at the time of his marriage, John is a ‘mechanic’ employed by Asa Lees a manufacturer of textile machinery (see advertisement). At this time John is living at 67 Mount Street, just off Glodwick Road, and close to the Soho Iron Works of Asa Lees that was located in Townfield between Greenacres Road and Lees Road (see Chapter 5); and not very far from Sarah’s home in Bellfield. Whether the couple met while John was still working in the cotton mill, or in church we’ll never know. I will return to John and Sarah later, but now I’d like to introduce the first member of the family to venture across the Atlantic – John’s brother Joseph.