“The most magnificent buildings…were Victorian, black with age. Derelict mills were everywhere, with empty windows full of nothing but sky. We lived in the ruins of a lost civilization. Glory and romance were in the past, almost out of reach,…” — Susanna Clarke, The Guardian (July 2018)

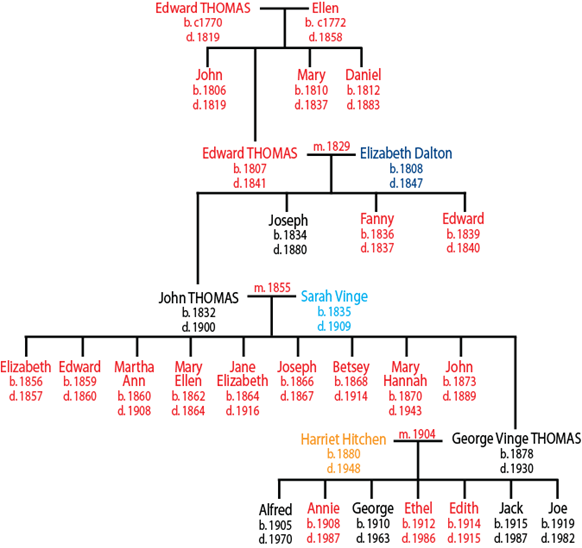

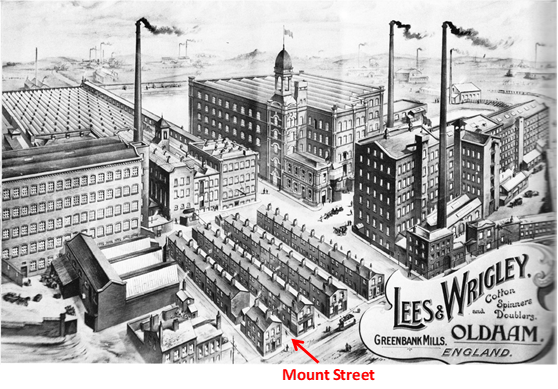

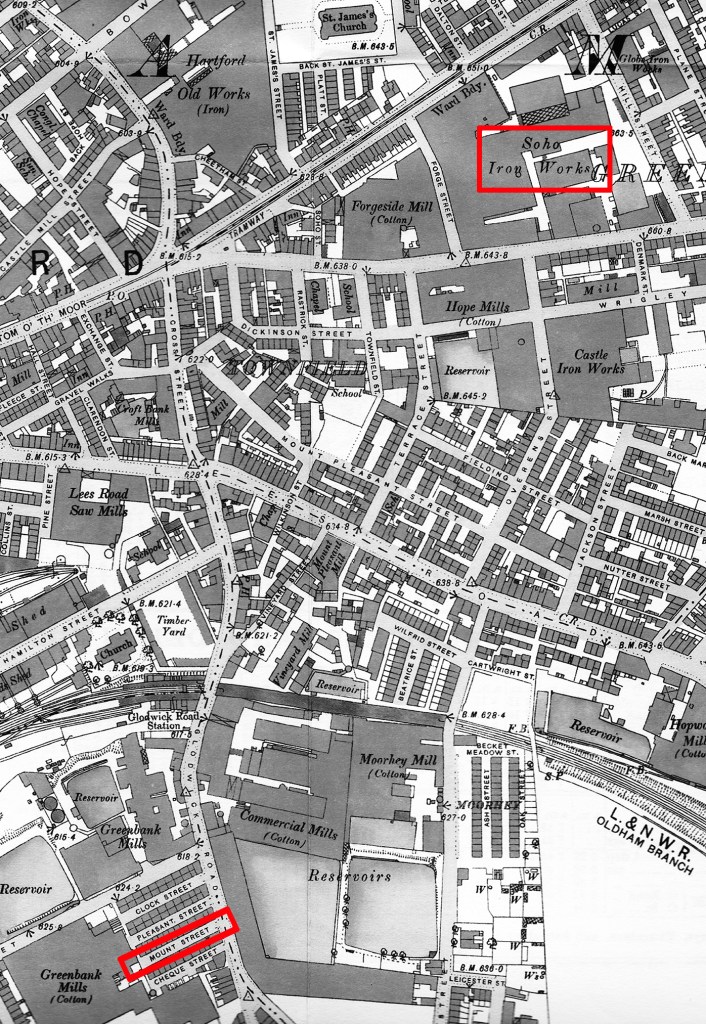

At the time of the 1851 census John and Joseph Thomas were living with their aunt and uncle, Sally and John Wood, in ‘Furtherfield’. Looking at adjacent areas in the same census, Furtherfield lies between Moorhey Road (now Street) and ‘Greenbank’; the next area being ‘Greengate’. The Greenbank Cotton Mills are at the corner of Greengate Street and Glodwick Road, so it seems that Furtherfield is somewhere close to the present Glodwick Road. Indeed in 1855 John is living in Mount Street (see map below) which may well be in Furtherfield.

In 1851, both John and Joseph were working as piecers in a cotton mill. Piecing was generally a child’s job which entailed joining broken threads that were generated during spinning. Apparently piecers tended to be employed directly by the spinner rather than the mill owner, and spinners would more often than not employ their own children. Considering John’s and Joseph’s uncle, John Wood, was a spinner it’s possible that he employed one or both of the boys as his piecer/s. As for what mill they worked in, the largest mills in the Glodwick area were those of Collinge & Lancashire (Commercial Mills), as mentioned in Chapter 1 the first in Oldham to install power looms. The Commercial Mills lie between Moorhey Street and Glodwick Road (see map below) and, as mentioned above, Greenbank Mills (see advertisement, below) are across Glodwick road, at the corner of Greengate street. The latter mills are very close to Mount Street where John was living just a few years later when he married Sarah Vinge (see Chapter 3). Also shown in the advertisement is the type of housing that came to dominate the town in the latter half of the 19th century. Row upon row of terraces to house the thousands of mill workers needed by over a hundred mills that were built in Oldham in the middle of the 19th century. These houses were of two basic types: the ‘back-to-back’, and the ‘through terrace’ (see Olusoga & Backe-Hansen, 2020). Both were generally two-storey, brick-built houses.

The back-to-back was so-called because the houses had no backyards, but were bordered on three sides by other houses with only windows at the front. This meant that there was no flow through of air for ventilation. Also, the partition walls between the properties were extremely thin – sometime only a half-brick width. The back-to-back would generally consist of only two rooms, a main room downstairs used as both a kitchen and living room, and a bedroom upstairs reached via a narrow staircase. The arrangement of the back-to-backs varied depending on the space available, but often they were found surrounding a small courtyard containing a water-pump and a privy; each of which was shared by all the residents of the court. Examination of the 1891 Ordnance Survey map of Oldham, and the advertisement above, shows that Mount Street consists of such back-to-back houses, but not in a court configuration.

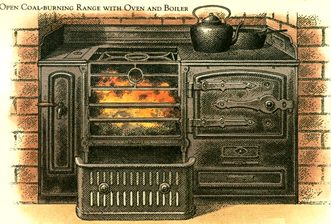

In contrast, the through-terrace houses had a backyard, and windows at the back allowing better ventilation. These dwellings were designed for families, and would have had four rooms, two downstairs and two bedrooms above. If the residents were lucky they might have their own yard and privy; although, I remember in our first house (on Airey Street) the yard (and privy) was shared with three or four other houses. In the better quality housing the kitchen might have an open range used for cooking, and to provide heat and hot water; perhaps similar to the one in the illustration above. After his marriage to Sarah, John and his family would live in such through-terraced houses on Heap Street, Greenacres Road and Greenwood Street (see below).

In terms of dress, for men the breeches of former centuries would have been replaced by trousers, and linen underwear and shirts would be covered by a waistcoat and long jacket or overcoat. For the most part the trousers and coats being made from hard-wearing rough fabrics such as fustian. Women would have also worn linen blouses and underwear covered by long skirts and aprons. In the manufacturing districts of the north, women would also make use of heavy shawls to keep warm and dry. Both men and women in Lancashire would have worn heavy-duty clogs rather than leather shoes. The clogs having laced leather uppers on wooden soles bearing iron runners.

In 1855 the banns of John’s marriage to Sarah show that John is not only living in Mount Street, but has also changed jobs. He is now working in the engineering industry as a ‘mechanic’ for Asa Lees & Co. Ltd.. In moving from the cotton mill to an engineering company, he would become the first of four generations of Thomas engineers in Oldham. It seems that John saw an opportunity to better himself and to improve his future prospects by joining an industry that, at the time, was undergoing massive growth. In the late 18th century engineering was dominated by skilled engineers (millwrights) who, after a stringent seven-year apprenticeship, were able to make sophisticated machinery by hand – such men often commanded very high wages, and were often referred to as ‘labour aristocracy’. Nevertheless, the demands of the booming cotton and railway industries were such that relying on hand-made machines from a limited number of skilled workers was completely inadequate. Engineering companies began to look to technological developments that would replace these skilled workmen with machines that could be run by unskilled or semi-skilled workmen. It would seem that John was one of these unskilled/semi-skilled young men who were attracted by better working conditions, and wages, than were available in the local spinning mills.

The problem for the skilled millwrights was that the tolerances achievable in producing parts by hand was very poor, and the reproducibility even poorer. A simple example is the production of screws – a vital component of all machines. Until the introduction of the metal lathe by Henry Maudslay around 1800, screws were made by hand. The tools used were of the crudest kind and more often than not the millwright would cut screws by hand using a small file for small screws, and then chipping and filing larger screws. So, the screws made by one manufacturing establishment rarely fitted a machine made by another manufacturer. With the increasing need for more engines, spinning mules, looms, etc., it was impossible for the skilled, artisan millwrights to meet the demand. To solve this problem, manufacturers turned to the newly-invented machines, such as metal lathes and planing machines, to make tools and components for their products. These ‘machine tools’ increased the speed of production and achieved far better tolerances than millwrights could. Not only did these machine tools increase the speed of manufacture, they also led to standardization of component sizes, screw-threads, etc.. Additionally, men could be quickly trained to run just a single machine churning out hundreds of screws or bolts or spindles as needed.

The engineering industry moves north

In the early days of engineering (1780-1820) London was the centre of the industry with, in 1825, about 500 small firms each employing fewer than 20 workers; however, by 1851 the number of companies in London had fallen to less than 170 (albeit still employing over 6,500 men). From 1830 to 1850 the centre of the engineering industry would shift to south Lancashire, and engineering would be transformed from a labour-intensive industry dominated by the individual millwright to a capital-intensive industry dominated by machine tools and machinists such as John Thomas. This fact is shown clearly by the fact that the average London firm in 1851 was employing fewer than 40 men, in comparison Hibbert & Platt making textile machinery in Oldham was employing over 1,500 men. It was the growth of the textile industry and the consequent demand for looms and mules that drove the development of textile machinery manufacture in south Lancashire. Likewise, the success of the railway from Liverpool to Manchester spurred the growth of the locomotive makers such as the Vulcan Foundry of Newton-le-Willows and Sharp, Roberts & Co. of Manchester. Of course, all of this growth was only possible because of the development and manufacture of machine tools by companies in south Lancashire such as Joseph Whitworth of Manchester and Nasmyth, Gaskell & Co. of Patricroft (also known as the Bridgewater Foundry). These were the firms that provided the lathes, the self-acting planing, shaping, nut-cutting and facing machines that revolutionized machine manufacture in south Lancashire. By 1856, Sir Joseph Whitworth calculated that the replacement of chipping and filing by the planing machine reduced the cost of levelling the surface of cast iron from 12 shillings (or 144 pence) to 1 pence per square foot. This reduction in cost was brought about both by the speed at which the planing machine worked, but also by the reduction in wages. A skilled millwright in 1825 might earn 7 shillings a day, whereas a machinist in 1850 was paid about 3 shillings. Furthermore, instead of employing four millwrights and an apprentice, a manufacturer might employ a single qualified mechanic assisted by four semi-skilled machinists. Of course in order to achieve this lowering in cost, the manufacturer had to first buy the planing machine which might set him back more than £500! One of the consequences of the high capital costs of the equipment was that manufacturers needed to keep these machines running as long as possible which, in turn, led to overtime working.

Industry growth pangs and the 1852 lock-out

As a result of all the changes during this period (1830-1850) the millwrights struggled to maintain their dominance of the industry. Perhaps the straws that broke the camel’s back were the introduction of ‘systematic overtime’ and ‘piece-work’. The latter a direct result of the ease with which a manufacturer could measure the efficiency of his workers. Instead of paying workers by the hour, the employers found it much more economical to pay a worker based on the number of items he made during the day. The efforts of the mechanics to avoid these impositions led to the formation of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE) in 1851 and the subsequent 1852 lock-out. In fact the 1852 lock-out perhaps marks a major turning point in the evolution of engineering in Britain and, interestingly, had its roots in Oldham. The engineering industry as a whole underwent a major depression in the mid 1840s, but around the end of the decade the industry began to come out of its economic slump. In order to take full advantage of the increase in trade, many of the major manufacturers began to install the machine tools being created by the likes of Nasmyth and Whitworth. In doing so the manufacturers could keep the cost of manufacture down to pre-slump levels, or even lower, despite the fact they were employing more men. By using machine tools each man could produce far more nuts, bolts, etc. than a skilled artisan could with simple tools. In his autobiography Thomas Wood, a skilled mechanic, describes how he took a job with Hibbert & Platt in Oldham in 1845: “…I commenced work for a firm who employed near 2,000 hands, whose tools were mostly Whitworth’s make – I, who had…(worked)…with country-made tools, the very best of which Platts would have thrown away as useless.” (Griffin, 2013). And, he adds: “Men in large shops are not troubled with a variety of work and special tools. The men soon became expert and turned out a large quantity of work with the requisite exactness without a little of the thought required of those who work in small shops…”. Just six years later, this very firm of Hibbert and Platt would witness the beginnings of the 1852 lock-out.

The up-turn in fortunes for the engineering manufacturers also signalled an increase in bargaining power for the artisan mechanics. As a result, there followed several industrial disputes in the period 1850-51 (see Burgess, 1972). In several of these the employers were forced to back down and accept the workers demands, but in April 1851 the workers of Hibbert & Platt pushed just a little too far. The ASE had been pressing the employers to abandon systematic overtime and piece work for some time, and these two demands were presented to Mr. Platt by his work-force in 1851. However, the Oldham engineers also demanded that he lay-off ‘illegal’ men (those who hadn’t undergone apprenticeships) and replace them with apprenticed workers. On May 6th, Platt agreed to end systematic overtime and piece-work, but initially refused to fire the illegal workers. The engineers gave him an ultimatum that they would strike if he didn’t accede to their demands by the 17th. On the 16th an agreement was reached and a strike was averted. However, unbeknownst to the work-force, on the 13th May Platt had met with twenty other major Lancashire manufacturers in Manchester who agreed to form an ‘Association of Employers’ for their ‘mutual aid’.

Subsequently in December, with the support of the other manufacturers, Platt decided to disregard the previous settlement, and all the employers vowed to lock-out their men if the workers of Hibbert & Platt voted to strike. The ASE tried to dissociate itself from the demands of the Oldham engineers by restating its policy in favour of an end to systematic overtime and piece-work, but stressing that it made no demands on the sacking of illegal men. In contrast, the Association of Employers spread the idea that the removal of illegal men was a central demand of the ASE. Burgess (1972) has claimed that ASE didn’t actively support the removal of the illegal men; however, Murphy (1978) has argued that at certain points in the negotiations the ASE had indeed demanded that Platt should dismiss the illegal men. An ASE executive (Mr. Newton) had agreed with Platt that such dismissals could be postponed to a later date (when Platt had fulfilled a large order to Russia), and only if other employers did the same. Whatever the truth of these various interpretations, the Lancashire employers gained a lot of public support and were joined by several of the large London firms to form the ‘Central Association of Employers of Operative Engineers’. Ultimately the employers closed their gates and locked-out the workers on the 10th January 1852.

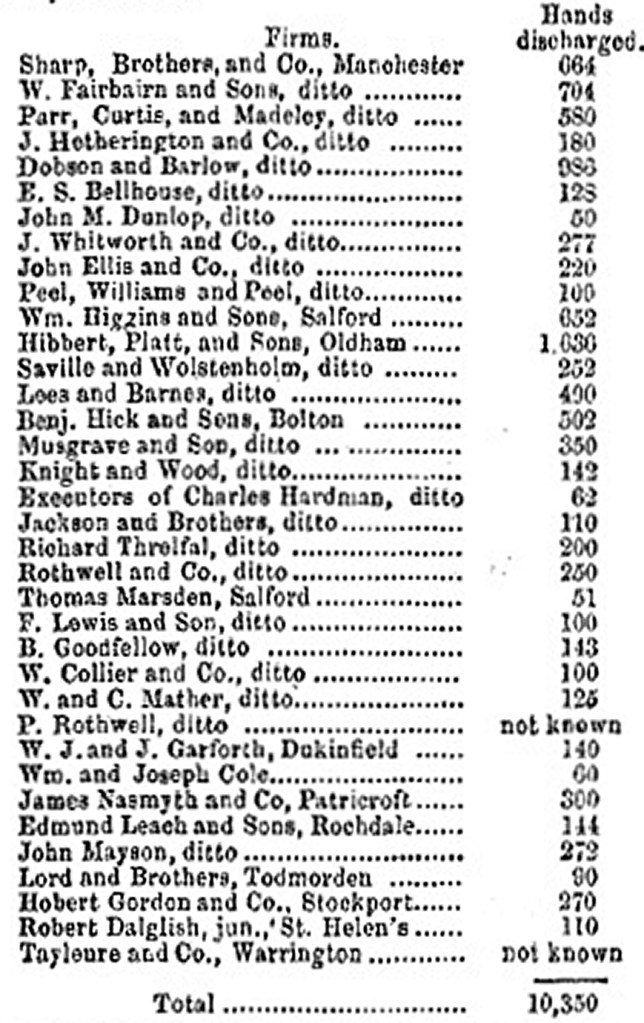

Twelve of the largest firms in London employing around 3,500 men were involved in the lock-out, together with 36 firms in Lancashire who employed 10,350 men (see above). Of the latter, the three largest firms in Oldham all locked-out their workers: Hibbert & Platt (1,636 men), Lees & Barnes (490 men) and Seville & Woolstenhulme (252 men). Despite the fact that the ASE looked upon the original dispute as a ‘local matter’ between Hibbert & Platt and its workmen, the union still felt obliged to support all of the locked-out workers, the majority of whom were not members. By April the union was finding it impossible to find the money to pay the out-of-work men (it had imposed a levy on its members of one-day’s pay per week to try to cover the costs), and on the 29th the ASE declared the lock-out was at an end, and the skilled men returned to work with none of their demands met.

As already mentioned, at the time of the 1851 census John was 18 and working in the cotton mill, but by the time of his marriage in 1855, he is a mechanic at the Soho Iron works of Lees & Barnes. Likewise, John’s brother Joseph was also described in the record of his marriage in 1857 as an ‘iron planer’ (perhaps with the same company?). So, both brothers had moved from the cotton industry to jobs in engineering. One can’t help but speculate that the employers’ success in defeating the ASE in the 1852 lock-out helped to ease the way for the hire of many more so-called ‘illegal’ men such as John and Joseph who had not completed apprenticeships. In terms of my family history this was a pivotal step – John and Joseph would represent the first generation of Thomas engineers.

I suspect that this was also a step upwards for John’s family, both financially and socially. After paying his piecer, John’s uncle (John Wood) as a spinner in a cotton mill would have taken home about 15 shillings (75p) for a 60-hour week in 1859; in contrast John, as a machinist in an engineering factory, might have earned about 20 shillings (£1) for a 58-hour week (Chadwick, 1860). Indeed, in unpublished work of 1846-47 (see Shaw, 1887), Edwin Butterworth writes: “The conditions of the operative Machine makers, Iron founders and similar workmen is equal to that of the best class of factory operatives.”.

Ultimately, John’s son, George, would work as an iron turner, and each of his four grandsons (Alfred, George, Jack and Joe) would find jobs in engineering, with my grandfather (Alfred) being described in the 1939 Register as a ‘Jig and Tool Inspector (Aircraft)’ – a source of great pride to my father that his dad was skilled enough to work to tolerances of thousandths of an inch – a latter-day ‘labour aristocrat’! Finally, my uncle would become the fourth generation Thomas to enter the engineering industry, working for many years as a draughtsman at Platt Bros. & Company – the direct descendant of Hibbert & Platt.

Luck or education

Was John’s move into the engineering industry a matter of chance, or does it show a certain degree of good judgement and intelligence? It’s difficult to know the type, or extent, of education that John and Sarah would have received. In Bread for all (2017) Chris Renwick states that in the 19th century “Children went to different types of school, for different lengths of time, depending on their social class”. Estimates of literacy in England at the beginning of the 19th century suggest that 40% of men and 60% of women were illiterate. It’s thought that education of girls put more emphasis on needlework than reading and writing, which may explain the differences in literacy between the sexes – indeed, why Sarah only made her ‘mark’ on their marriage certificate, whereas John was able to sign it. Until 1833, education of working-class children had relied upon schools funded by charities and philanthropists to provide a basic education (e.g., Ragged Schools). However just a year after John’s birth, the Government decided it had to try to improve the education of poorer children, and started to dispense grants for education amounting to £20,000 in the first year. The amounts granted increased in subsequent years, reaching £260,000 in 1853, and by 1850 the Government had spent about £750,000 on children’s’ education. According to the 1851 Educational Census in the years between 1839 and 1850, £405,000 was given to Church of England schools, £8,000 to Wesleyan schools, £1,049 to Roman Catholic schools and £37,000 to workhouse schools. Nevertheless, by 1850 illiteracy amongst men had still only fallen to 36%, and a survey in 1851 estimated that fewer than 50% of children in Manchester were receiving any form of education.

Perhaps John, and his brother Joseph, were some of the lucky ones. Both boys (and their sister, Fanny) were christened at St. Peter’s Church which was the site of the first Sunday school created in Oldham in 1783 by the Rector Thomas Fawcett (also, first headmaster of the Grammar school). A report by the Inspector of Factories in 1842 (see Fox, 1964) states that St Peter’s Infant day school was one of only three public day schools in the town. At that time the school taught about 100 pupils, and John would have been ten years old and Joseph just eight. The Factory Act of 1833 had made it illegal for the mill owners to employ children younger than nine; so, it’s possible that John and Joseph attended this school before the age of nine. The Act also restricted employment of children between nine and 13 to only eight hours a day and six days a week; i.e., 48 hrs per week. In addition, it was stipulated that children employed in the mills should have some form of schooling, and that this might be paid for by the deduction of no more than a penny in every shilling from the child’s earnings. Children between the age of nine and 13 were also allowed to work for more than 48 hours if they provided a certificate indicating that they had received two hours of school each day of six days in a week. These regulations were not very well enforced, but at least set some boundaries on the employment of very young children in the mills.

The 1851 Educational Census showed that, in Oldham, there were 26 public day schools of which 17 were church run, six were funded by charitable endowments (including the Grammar school and the Bluecoat school), there was a factory school (at Derker), the workhouse school, and the Mechanics’ Institute. These schools had 3,437 pupils, with another 3,660 pupils being taught in 65 private day schools – this in a town of over 72,000 people (inc., Chadderton, Royton and Crompton). In contrast to just 7,097 children in day schools, the census shows that there were 17,663 children attending Sunday schools. One of the largest of these Sunday schools was associated with Greenacres Congregational Church (see Chapter 3) where Sarah had been baptized in 1835. In 1848, according to O’Neil (1848), this school had 43 teachers and was attended by 360 pupils. The number of teachers sounds impressive, but it should be borne in mind that at this time most schools used the ‘Lancasterian’ or Monitorial system. This form of teaching was developed by Joseph Lancaster early in the 19th century (and independently by Andrew Bell), and involved the use of older or more advanced pupils as helpers for the main teacher, passing on the knowledge they had gained to the younger, less able students. It’s likely that Sarah may have received a limited education at this school. The fact that John could write (and presumably, read) suggests he probably got a better education than his wife, and some of his contemporaries, which may explain why he made the jump from the cotton mill into the engineering industry.

Growth of town and family

John and his wife Sarah would live through a time of enormous growth and development in Oldham. The town’s population would increase from just over 40,000 in 1841 to almost 140,000 by 1901 (the year after John’s death). They would have 10 children, four of whom (Elizabeth, Edward, Mary Ellen, and Joseph) would die before they reached the age of three, and another (John Jr.) who would die in his teens. Of the five surviving children, four were girls (Martha Ann, b. 1860; Jane Elizabeth, b. 1864; Betsy, b. 1868 and Mary Hannah, b. 1870) and the only boy, my great, grandfather (George Vinge, b. 1878). The family do not appear in the 1861 census, but in the record of Edward’s baptism in 1859 their address is noted as Heap Street. In the 1871 census John, Sarah, Martha Ann, Jane Elizabeth, Betsy and Mary Hannah are living at 4 Heap Street, off Greenacres Road, very close to John’s workplace. As we’ve seen in Chapter 4, John’s brother Joseph and his family had emigrated to the USA in 1869. Likewise his uncle Daniel (see Chapter 3) had moved to Hyde, so by 1870, John and his children are the only Thomases left in Oldham descended from the Welsh couple, Edward and Ellen, who arrived in the town around 1805 (see Chapter 2 and family tree, below).

By 1881 there were two more children (John Jr. and George Vinge) and the family had moved to 133 Greenacres Road – presumably a larger house to accommodate the enlarged family. From the 1907 Ordnance Survey map of East Oldham, I think this house was on the left-hand side of the road (on the way out of town) perhaps between the junctions of Dunkerley Street and Mortar Street. Also living with the family was Sarah’s father, George Vinge (see Chapter 3), after whom Sarah had named her youngest son. By 1891, the four girls had all married and left home, both Sarah’s father (1887) and their son John Jr. (1889) had died, leaving just George living with his parents, now at 89 Greenwood Street (perhaps a smaller property?). This house would have been on the left-hand side of the road (heading away from town) between Kershaw Street and Spring Street, perhaps opposite Taurus Street and the Star Picturedrome.

Voting reform

John and Sarah were born after the Great Reform Act of 1832, but Sarah would never be able to vote and John would be about 35 when he obtained his suffrage. The Great Reform Act of 1832 had created the new constituency of Oldham which returned two MPs (see Chapter 1), however only those men over 21 years of age who owned property valued at £10 or more could vote (approx. 18% of the adult male population). After Lord Palmerston’s death in 1865, Lord John Russell became the next Liberal Prime Minister and attempted to increase the franchise to ‘respectable working men’; however, his bill failed and Russell resigned. Russell was succeeded by Gladstone, another in favour of electoral reform, but the Conservatives managed to form a minority government with Lord Derby as Prime Minister. Derby was not in favour of reform, but his Chancellor, Disraeli, convinced him that reform was bound to happen eventually. The Chancellor also argued that if they were to implement reform it would reflect well on the Conservatives and to the detriment of the Liberals in the event of a future election.

Ultimately, the Conservatives’ second reform act or Representation of the People Act of 1867 was passed and extended the vote to those men in urban areas who rented, as long as the rent was at least £10 per annum. The idea was to give the vote to skilled craftsmen, but exclude unskilled workers and the un-employed. This second act increased the number of eligible voters from about 1 million to 2 million men over the age of 21, about a third of the adult male population. Amongst these new voters was John Thomas who appears in the Burgess Rolls of Electors in 1867 to 1869 and the Electoral Rolls of 1872 at 4 Heap Street, and from 1873 to 1882 at 133 Greenacres Road, and finally from 1883 to 1900 at 89 Greenwood Street.

Changes to the fabric of the town

John’s life almost exactly coincided with the reign of Queen Victoria, being born just five years before she came to the throne and pre-deceasing his monarch by only 10 months. The ‘Victorian’ era is often viewed as one dominated by stuffiness and stifling conventionality, but in reality it was a time of incredible energy and confidence – a self-belief that led to massive changes in the fabric of Britain’s towns and industry. In the Great Exhibition of 1851, Britain sold itself as the world leader in the supplier of high quality machinery and textiles, all housed in a marvel of Victorian construction – The Crystal Palace. The latter a prime example of the buildings that would spring up across the country transforming old towns and creating new cities, Oldham being no exception. As a child I remember that, apart from some churches, all the major buildings in the town were built during this period – the Town Hall, the Library, the Lyceum, the Central Baths, the Market Hall, the General Hospital (originally the Workhouse) and Royal Infirmary, Werneth Fire Station and, of course, the numerous cotton mills that were still standing (over 130 built between 1841 and 1883). For John and Sarah the transformation of the town over their lifetimes must have been quite remarkable.

The growth of the cotton-spinning business in Oldham during John’s life would mean that, apart from the depression during the America Civil War (see Chapter 4), his job was relatively secure. The company he worked for, Asa Lees & Co. made all kinds of textile machinery, but concentrated on the spinning machinery which was at the heart of the local industry. It was the second-largest machine maker in town, but only about a quarter of the size of the largest firm, Hibbert & Platt. Asa Lees employing around 3,000 workers at the time of John’s death in 1900. The size of the company reflected a certain degree of conservatism in its management, which also led to the fact that the company remained profitable even when its competitors made a loss. Lees’s shareholders always receiving a dividend up until the company merged with several other textile-machinery makers (including Platt Bros.) to form Textile Machinery Makers (TMM) in 1931.

John and Sarah’s daughters

John and Sarah are the first couple in my Thomas line of descent who had female children who went on to marry and have children. In my introduction to this family history I promised not to allow the story to become “…just a dry, chronological list of births, marriages and deaths.”. Nevertheless, I felt I had to include some information on the descendants of John’s and Sarah’s daughters so that those Oldham family historians who have a Thomas in their family tree might find a connection to this story. To prevent boredom for those for which this information is of no interest, I’ve included the majority of the data in table form.

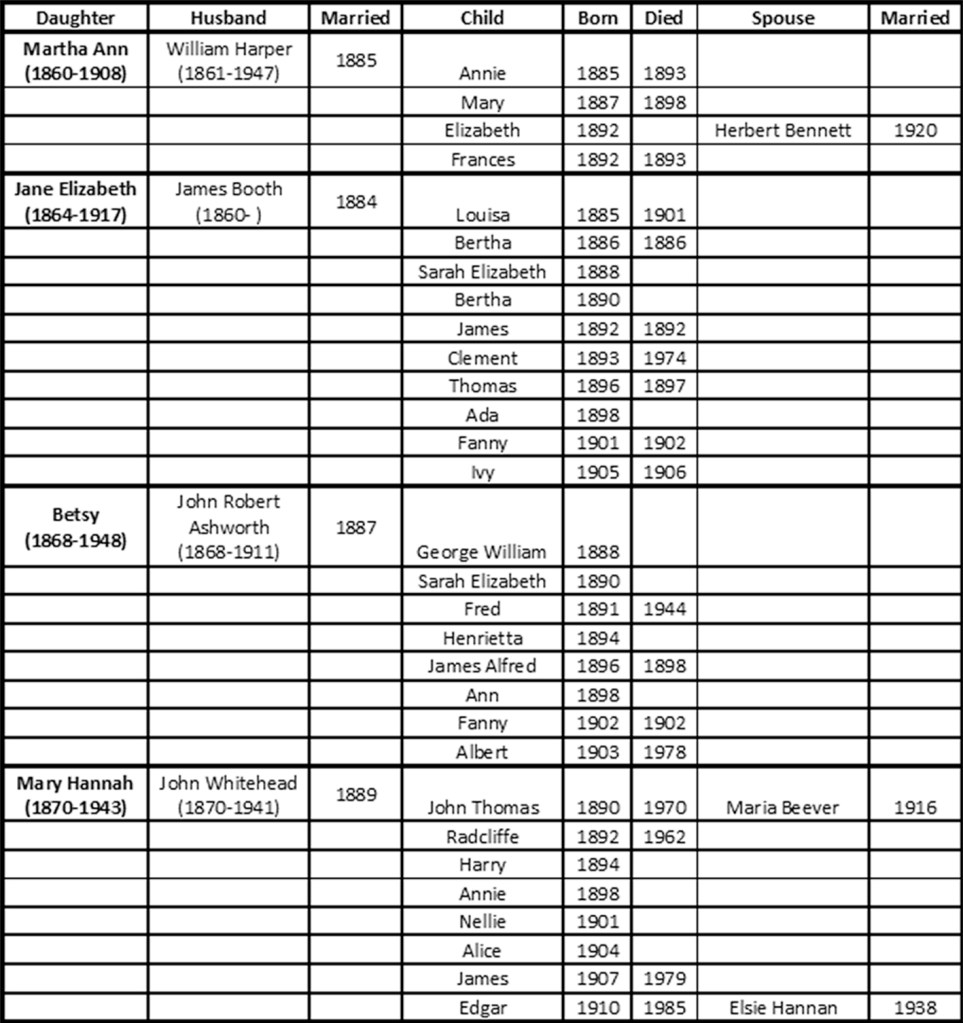

John’s and Sarah’s eldest daughter Martha Ann would marry a William Harper and have four daughters, three of whom would die in childhood (see table). Martha’s husband, William, was a ‘School Attendance Officer’. This was an occupation that became very important following the Elementary Education Act of 1880 which made it compulsory for children between the ages of five and ten to attend school. Martha would die in 1908, and William would re-marry in 1910 to Emma Smith (the widow of an Edward Bowers).

Martha’s younger sister Jane Elizabeth married a journeyman clogger by the name of James Booth. This couple had ten children, five who died before the age of two years and one in her teens (see table). Jane would die in 1916 at the age of 51.

In 1887, the third Thomas daughter, Betsy, married John Robert Ashworth at St James’s Church on Barry street. They would have six children who reached adulthood (see table). In the 1901 census John is described as an ‘iron labourer’. Of course, Betsy’s father was variously described as a ‘mechanic’, ‘iron labourer’ or ‘iron turner’, so perhaps John Thomas and John Ashworth were work colleagues? One of Betsy’s sons, George, would become a moulder at an iron works, maybe following in his father’s footsteps. Considering where the family lived, on the south-western edge of Waterhead, the Ashworth men would have a multitude of employers to choose from, not only Asa Lees, but also the other major machine maker Platt Bros. (Old Hartford Works), the engine makers Buckley & Taylor (Castle Iron Works) and W. B. Haigh & Co. (Globe Iron Works), or several other smaller concerns, e.g. the Star Iron Works of W. Toole on Taurus street.

The youngest daughter Mary Hannah married John Whitehead at St James’s Church in 1889. John started working in the cotton mill as a piecer, later as a spinner, but eventually would enter the building trade as a slater’s labourer. Mary and John would have eight children, all who survived into adulthood (see table below).

The end of an era

John Thomas would die in March 1900, and just months later in January of the following year Queen Victoria would also pass away. Following John’s death, Mary Hannah and John Whitehead would take in her mother and brother, Sarah and George. At this time the Whitehead family were living in Court no. 2, Nicholls Street (off Horsedge St; between Rock St and Egerton St). John had died of old age – “Senility 4 months, exhaustion 7 days”, and Sarah would pass away eight years later from basically the same cause – “Senile decay, Bronchitis 2 months”. In the next chapter I will continue with the story of John’s and Sarah’s remaining child, my great grandfather George Vinge Thomas.