“We have concluded that it would be impossible to carry out the rules of the rugby union, and decided to form a new union more in touch with present-day football, and with a special view to meeting the requirements of the working man player.” — Joseph Platt, Treasurer of Oldham FC and first Secretary of the Northern Union (1895)

I ended the last chapter with the deaths of my great, great grandparents, John and Sarah. The couple’s youngest child was my great grandfather George Vinge Thomas who had provided the motivation for starting this journey through my family history (see Introduction). If you’ve read any of the previous chapters you’ll already realize that the family story of George’s move from Wales to Oldham to play rugby is a myth. His parents and his grandparents were all born in South-East Lancashire. Did George play rugby for Oldham? I don’t think so, but did he play rugby at an amateur level or for one of clubs in the Lancashire Second Competition of the Northern Union (Werneth or Crompton)? That’s always a possibility. However, it seems clear he earned his living in engineering just like his father. In the 1901 census George is described as an iron turner, and again in 1911 as an iron turner in the ‘Motor Trade’. In the record of his death in 1930 George is described as an iron turner ‘Sewing Machine Makers’.

Sewing machines and cars

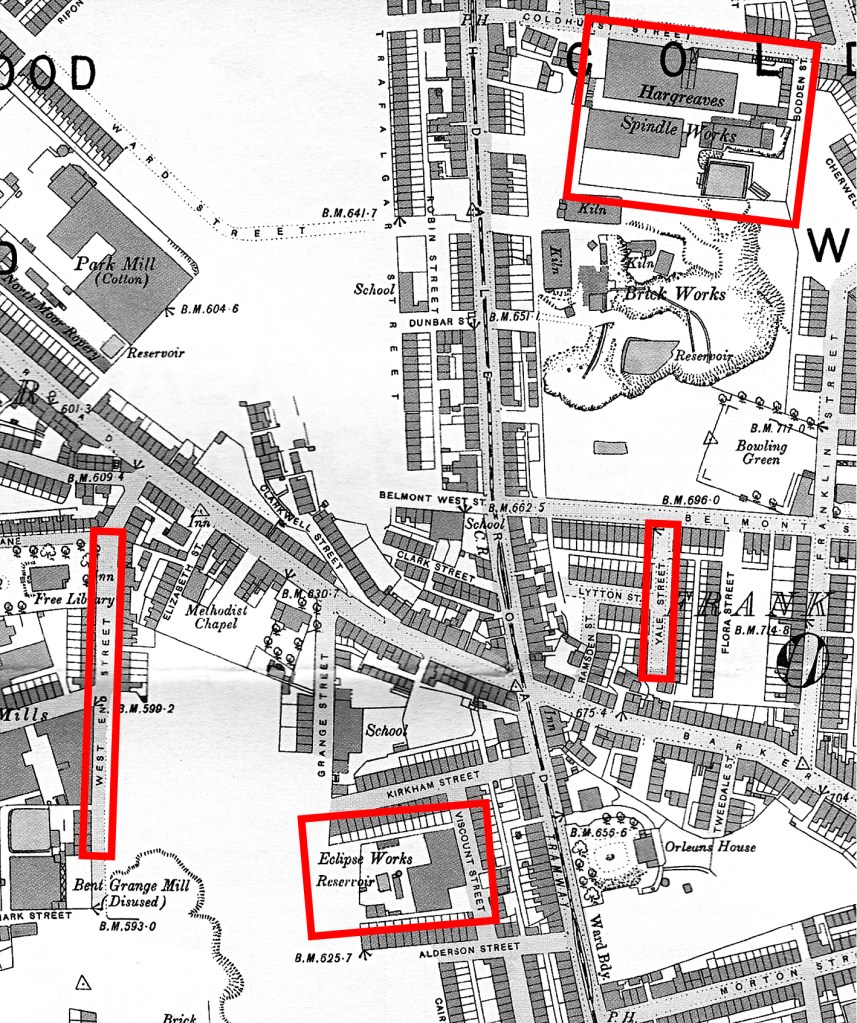

There were two main sewing machine manufacturers in Oldham, both of which also produced motor cycles and cars. The smaller of the two companies, but the closer to where George was living at the time of his marriage, was the Eclipse Machine Co. on Viscount Street. This street no longer exists, but used to run parallel to Rochdale Road between Alderson and Kirkham Streets (see map below, and Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History). Eclipse was formed as a sewing machine manufacturer by the partnership of Emanuel Shepherd, James Edward Hough, and the brothers Fred and Tom Rothwell around 1872. Later the company would branch out into the manufacture of motor vehicles, building cars between 1901 and 1916, as well as motorcycles from 1903 (see Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History; Boddy, 1963; and Warburton, 2010).

In 1904, the year of his marriage to Harriet Hitchen, George Vinge was living at 4 Yale Street and, following the wedding, the couple would move to Court 1, West End Street. This house in the court would have been a back-to-back, and a step down from the through terrace in Yale Street (see Chapter 5). The map below shows West End Street just to the west of the Eclipse Works and Yale Street less than half-a-mile from the factory on the other side of Rochdale Road.

There is some interesting information about the Rothwell brothers that suggest a connection between the two families. In Chapter 3 I mentioned that George’s father John was working for Asa Lees & Co. as a ‘mechanic – iron’ at the time of his marriage (1855). Likewise, Tom Rothwell worked for Asa Lees serving an apprenticeship as an iron turner there around 1860. In the 1851 census Tom’s father, David, is described as a ‘mechanic – iron’, and in the 1861 census David and his two sons, Tom and Fred, are all described as ‘mechanics – iron’ just like John Thomas. Additionally, in the same census, the Rothwell family are living on Greenacres Road just around the corner from Heap Street where John Thomas and his family were living. These facts may be purely coincidental, but they do raise the possibility that John Thomas and David, Tom and Fred Rothwell were acquainted. Did John move to Eclipse in 1872 when the company came into existence, or did he remain at Asa Lees? The fact that the Thomas family stayed living in Greenacres, and slowly moved to properties further from the town centre, and from the Eclipse Works, would suggest he remained with Asa Less throughout his working life (or at least with another company in the Greenacres area).

The Elementary Education Act of 1880 had made school attendance compulsory for children between five and 10 years old; so, George would probably have left school in 1888 just 10 years old. On leaving school, it’s likely that George served his apprenticeship with the same company that employed his father. In the 1891 census both John and his son (aged 13) are described as iron turners – George, presumably, having just begun his apprenticeship. At the time of his father’s death in March 1900 George would be 23, and have completed his apprenticeship, but may still have been working in Greenacres. However by the time of the 1901 census, George had moved into the town centre (living in Nicholls St) and eventually to Yale St (by January 1904). Maybe this change of location also coincided with a move to a different employer?

From the proximity of the Eclipse factory to George’s home I had assumed that this must be where he worked. However, on the release of the 1921 census I discovered that George was working at the other, much larger sewing machine manufacturer, Bradbury & Co.. Motor car manufacture at Eclipse virtually ceased with the start of the Great War. Tom Rothwell had retired from the business in 1911 (aged 66), and in 1914 his brother Fred would die. With the onset of war, the company received several contracts from the War Office for the most part producing munitions – grenades, Mill’s bombs, shells and steel darts. Whether George had worked at the Eclipse Works before the war, but later moved to Bradbury’s it’s impossible to know.

I’ve found no evidence that George served in the army, and indeed his two youngest sons (Jack and Joe) were both conceived during the war. George would have been 38 when conscription for married men between 18 and 41 was introduced in May 1916, so not too old. Nevertheless, it’s likely his employment as an engineer would have given him an exemption.

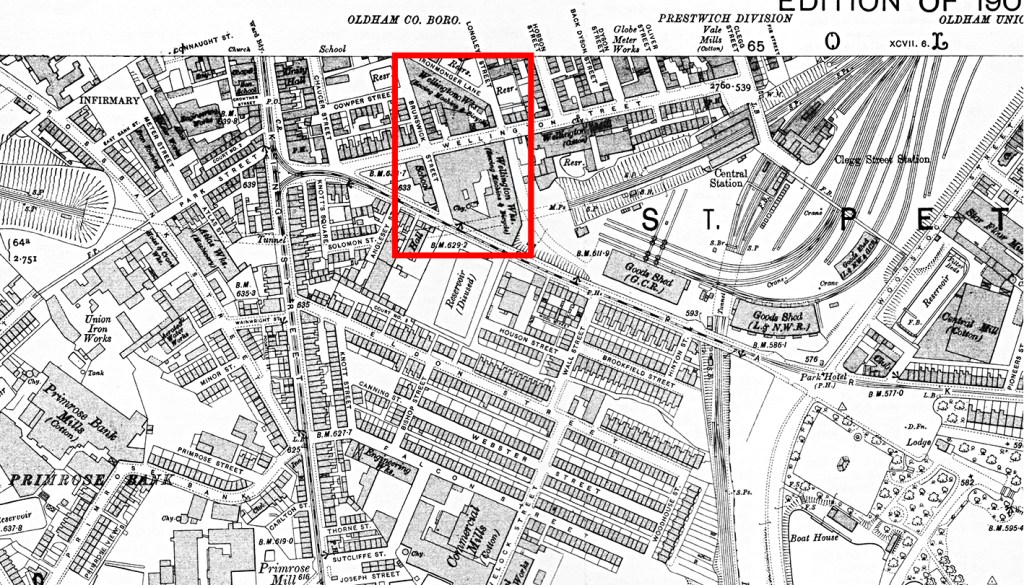

Bradbury & Co. (see Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History; and Sewmuse) was formed by the partnership of Fred Sugden, Tom Sugden, Joseph Firth and George F. Bradbury in 1852, but became Bradbury & Co. about 1858, and a Limited Company in 1874. The firm was the first to manufacture sewing machines in Britain (and possibly Europe). It’s thought that George Bradbury began working for Hibbert, Platt & Sons, but left as a result of an industrial dispute. It seems likely this dispute was the 1852 lock-out that I described in the previous chapter, and which led to major restructuring of the engineering industry with the employment of ‘illegal’ workers such as John and Joseph Thomas.

Bradbury’s was located at the Wellington Works on Wellington Street between Brunswick Street and Longley Street close to the junction with Park Road (see map above). From examination of the OS maps of Oldham from 1891 and 1906, I’d estimate that the Wellington Works covered an area about 5x the size of the Eclipse Works. By 1875 the company employed around 500 workers, and had begun to produce bicycles and tools in addition to sewing machines. Around 1890 there were about 600 staff on the manufacturing side which were producing 25-30,000 sewing machines per annum. At the time of George’s father’s death, and George’s move to the centre of town (closer to Bradbury’s), the company had begun to make motor cycles and tried to enter the motor car industry – producing three-wheeler vehicles (see illustration below). At the end of 1905 the company had grown to such an extent that 1500 workers were involved in manufacture.

The Hitchens

George’s wife Harriet was the daughter of John Samuel and Mary Jane Hitchen who also lived on Yale Street when George and Harriet were married. The Hitchen family originated in Yorkshire. John Samuel’s father, Alfred, was born in Sowerby (nr. Halifax) in 1826; however, Alfred’s parents, Joseph and Anne, had moved to the Oldham area sometime before 1833, when Alfred’s sister Elizabeth was born in Failsworth. By 1841 the family had moved to Hollinwood, and subsequently (by 1851) to Northmoor. At the time of his marriage in 1825 Joseph was working in a textile mill as a ‘twiner’. The twining machine was a modified spinning jenny in which two or three threads were twisted into one, so a twiner’s job was presumably running such a machine. Nevertheless in later life, he would end up working as a butcher. In the 1841 census Joseph was described as a shopkeeper in Hollinwood, so may have begun trading as a butcher soon after arriving in the Oldham area. He would have butcher’s shops in Northmoor (1851) and later in Busk (1861). Northmoor (Oldham) and Busk (Chadderton) are adjacent areas straddling Featherstall Road, north of Middleton Road, and south of Burnley Lane/Chadderton Road (previously Maygate Lane).

Alfred would eventually follow in his father’s footsteps into the meat-trade, but before this he would venture north to Co. Durham. Joseph’s sister Susannah had married a coal miner (John Ingham) from Bradford and had moved to Thornley in Co. Durham. In 1851 Alfred is working as a labourer and living with his aunt’s family close to Thornley Colliery. It would be here, just a few months after the 1851 census, that Alfred would marry Mary Smurthwaite, a native of Mordon near Sedgefield. Nevertheless by 1856 Alfred (and Mary) would be back in Oldham, and by 1861 he was running a butcher’s shop on Royton Road. In 1871 the address is 284 Rochdale Road – I’m guessing this is the same location, Royton Road having been renamed Rochdale Road. The couple would have four children, two daughters Tamer [b. 1856] and Hannah [b. 1861], and two sons Alfred (b. 1863) and John Samuel (b. 1859).

Like George Thomas, John Samuel Hitchen was also a mechanic, working as a fly or presser maker for a spindle and flyer makers. When John Samuel’s son, Alfred, decided to enlist in the Army at the start of the Great War he was just two weeks from completing his apprenticeship at William Bodden & Son. Bodden’s was a company of spindle and flyer makers based at the Hargreaves Works on Coldhurst Street (see map, above). Alfred was an apprentice presser maker, so I suspect both father and son worked for the same company doing the same job. Indeed the 1921 census reveals that John Samuel was indeed employed by Bodden’s at that time.

Despite the fact that he was just a few weeks from completing his apprenticeship, Alfred Hitchen decided to go to war (see Oldham Historical Research Group). This is most likely due to the fact that he had been a Territorial for about three years, and all his comrades would have been forming the Oldham Volunteers (10th) Battalion of the 1st Manchester Regiment. Alfred served in ‘A’ Company of the battalion in Egypt and Turkey. In Amateur soldiers: a history of Oldham’s volunteers & Territorials, 1859-1938 K.W. Mitchinson reports that having experienced the highlights of Cairo, Alf had thought it a “splendid (but) an absolutely immoral city”. However, Mitchinson went on to comment that “It is to be hoped that Alf Hitchen did, despite his reservations, derive some pleasure from its dubious delights for within a few months the 22-year-old from Yale Street was dead.”. Indeed, he didn’t even make it to 22, dying of his wounds on the Gallipoli peninsula on the 13th August 1915, just five days before his birthday.

The 10th Battalion of the 1st Manchesters formed part of the 126th Brigade of the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division – the first Territorial division to be sent overseas in the First World War. The division was sent to Egypt in September 1914 to protect the Suez Canal and then, in early May 1915, to Cape Helles on the Gallipoli peninsula. The 126th Brigade would have arrived in time to participate in the Third Battle of Krithia on the 4th June and later, on the 6th August, the Battle of Krithia Vineyard, during which Alf was wounded. According to a comrade (Pte. H. Powers) “(Alf) got over the top of the trench and ran back to the next trench in murderous fire, and fell in a lump at our Jim’s feet wounded.”. Alf Hitchen was posthumously awarded the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory medal. He is buried in grave G.58 in the Lancashire Landing Cemetery, Cape Helles, Turkey. His memorial inscription, provided by his parents, reads “For honour liberty and truth he sacrificed his glorious youth”.

As well as Alfred, John Samuel and his wife, Mary Jane Stone, would have seven other children, four of which would survive infancy. Amongst these was my great grandmother Harriet.

The Thomases

Harriet would have seven children with her husband George Thomas, four boys and three girls, one of whom would die in infancy (Edith d. 1915; 8 months). My grandfather, Alfred, was the eldest, born in 1905, followed by Annie (b. 1908), George Jr. (b. 1910), Ethel (b. 1912), Jack (b. 1915) and Joe (b. 1919). My grandfather Alfred and the older children may have left school as young as 12 but, due to the Education Act of 1918, Joe would have stayed on at school until he was 14 years old.

When my grandfather began his working life in 1917 the war would have still been ongoing. The 1921 census shows that he is an apprentice working as a turner for Bradbury’s where his father is a ‘tool turner’. As well as sewing machines and cycles Bradbury’s had also moved into making machine tools such as lathes. However, Bradbury’s would cease production in 1924, perhaps just in time for my grandfather to finish his apprenticeship. His father would also have been made redundant at the same time, however on his death certificate in 1930 he is described as a turner for a sewing machine manufacturer. This description would suggest that he remained unemployed for the last five or six years of his life because after 1924 there were no longer any sewing-machine manufacturers in Oldham (Eclipse also having closed its doors around 1922-23). It would also imply that my grandfather, and possibly his sister Annie, would have become the bread-winners for the family. However, another family story suggests a different source of income. My father told me that his grandfather, as well as coming from Wales (not true) and playing professional rugby (probably not true), was also a bookmaker. This would be at a time when bookmaking was illegal. Considering the unreliability of the other anecdotes about George, I am extremely sceptical about this tale. Nevertheless, bearing in mind the economics of the time and the lack of employment it‘s possible that George was forced into illegal activities to support his wife and six children, only one of whom would have been in full-time employment.

Although referred to as the ‘roaring twenties’, this period in Britain was far from roaring. British exports had begun to decrease dramatically, due both to an increase in manufacturing in the colonies and a large increase in manufacturing output from the USA and Japan. Because of shrinking overseas markets British manufacturers and mine owners attempted to increase their profit margins by pushing for longer working hours and wage cuts, in turn leading to many strikes and lock-outs. In 1925 this state of affairs would be exacerbated by the Chancellor’s (Winston Churchill) decision to return Britain to the gold standard – something that led to a major devaluation of the pound and a consequent decrease in living standards (see below The great depression; and Schama, 2002). As a result of all this economic turmoil the unemployment rate hardly ever dipped below 10% during the twenties, perhaps explaining my great grandfather’s lack of work.

On my father’s birth certificate (1931) my grandfather is described as a Journeyman, indicating that he had indeed successfully served his time. Unexpectedly he is not working as a lathe-operator, but as an ‘electrical fitter’. As expalined above, this situation may be a reflection of the times; i.e., with jobs at a premium Alfred may have taken any job he could get to support the family.

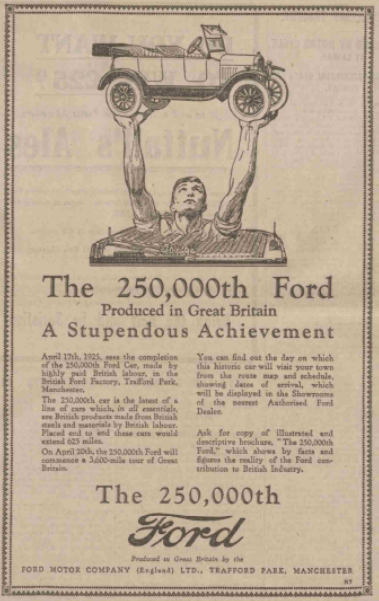

A major employer in the Manchester area that relied upon engineering expertise, but also on ‘fitters’ was the Ford Motor Company. I know that my grandfather had moved to Dagenham to work for Ford in 1931. Ford had begun assembly of Model T cars in the UK at its Trafford Park works around 1911-12, but in 1931 the company transferred all of its operations to its new factory in Dagenham. In a short history of Ford UK on the BBC (Essex) web-site it says “...over a single weekend in September 1931 special trains carried 2,000 employees, their families and possessions, from the Ford plant at Trafford Park, Manchester to their new life in Dagenham”. One conclusion from this statement is that my grandfather had actually started work at Ford before the move to Dagenham, and possibly as early as 1924 when Bradbury’s closed down. Furthermore, Alfred, his wife Kate and their young son, Alfred Jr. (my dad; just 8 months old), would have been amongst the families that were transported from the North West to Essex on that weekend in September.

As for Alfred’s siblings, in 1921 his sister Annie (aged 12) is described as a part-time, ‘little tenter’ (a person that looks after a spinning frame; ‘little’ because she was a child) at Highfield Mills, Chadwick Street. At the same time all his other siblings (except Joe, who was only two) were still in school. In 1939, Alfred’s sister Ethel, like Annie, is described as a tenter in the Cotton mill. Although I know all his brothers worked in engineering, I’ve not been able to determine where they served their apprenticeships. According to one of my father’s cousins her father, George Jr., began his working life with Textile Machinery Makers (either at the Asa Lees or the Platts site; for TMM see Chapter 5), and on his eldest daughter’s birth certificate in 1934 he is described as an iron turner. Joe is also described as a capstan lathe operator on his daughter’s birth certificate (1949). Whereas, Jack is described as a filing machine operator in the 1939 register. The latter was probably with A.V. Roe because his daughter told me that her father was working at Avros in Chadderton when he joined the navy in 1941.

The great depression

All four brothers would have been at the start of their working lives at the time of the great depression following the Wall Street crash of October 1929. In the years following the Great War there had been a severe economic depression with over a million unemployed in 1922. This situation gave rise to the formation of the National Unemployed Workers Movement (NUWM) which organized numerous so-called hunger marches throughout the twenties and thirties (1922, 1927, 1930, 1932, 1934 and 1936). By the early 1930s unemployment was approaching three million, affecting even the more prosperous areas of the Midlands and the South-East. The hunger march from Jarrow in 1936 is probably the most famous of these hunger marches, but perhaps the largest march was that of 1932 which carried a petition signed by a million people arguing against the Means test and the Anomalies Act (1931). According to The Manchester Guardian of 27th October 1932, a contingent of unemployed workers from Lancashire were amongst those on the hunger march carrying “red banners…[bearing] such inscriptions as ‘Down with the Means test’, ‘Down with the National Government’, ‘Lancashire Protests Against Baby-starvers’”.

The Means test was used to determine qualification for the dole. The Anomalies Act restricted the right of part-time and seasonal workers (and married women) to claim unemployment benefit. As well as the workers objections to this legislation, an additional trigger for the march was undoubtedly the 10% cut in unemployment benefit instituted by the government in 1931. Because of the high rate of unemployment and the excessive demands of the dole on government finances, the second Labour government of Ramsay MacDonald (1929-31) was forced to contemplate either increasing taxes or reducing unemployment benefits. The initial intention was to reduce the dole payments by 20%. However, this proved problematic and eventually a compromise proposal of a 10% decrease was put forward. Nevertheless, the Cabinet failed to agree and the government was forced to resign. The King asked MacDonald to stay on as Prime Minister, and with the co-operation of the Conservatives and Liberals, he formed the ‘First National Government’. It was this government that implemented the 10% cut to unemployment benefit, and it’s not too surprising that MacDonald was consequently labelled a traitor by his Labour colleagues and expelled from the party.

Such hunger marches were not just a feature of British politics, in the USA Ford cut back production and laid off thousands of unskilled workers resulting in the ‘Ford Hunger March’ on March 7th 1932 in which more than 60 men were shot by the police and Ford Security guards; ultimately, five men died. In contrast, a report in the Lancashire Daily Post of the 3rd February 1937 states that in June 1932, following the move from Manchester to Dagenham, Ford was employing 4,054 workers. By the following year this number had reached 7,000, by June 1936 over 8,000, and in February 1937 the total had grown to about 11,500. Perhaps my grandfather was one of the lucky ones working for Ford in the UK.

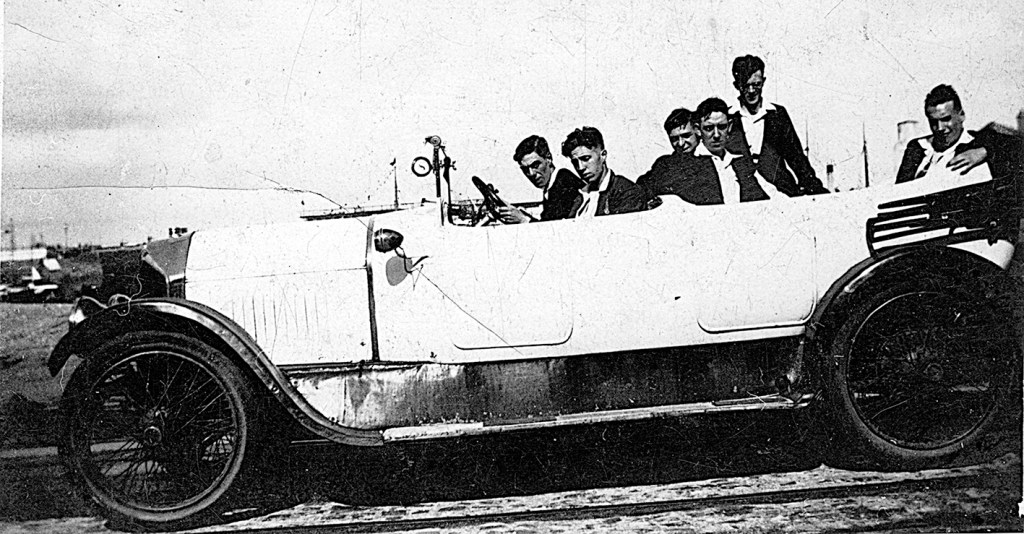

Nevertheless, my grandfather’s time with Ford in Dagenham appears to have been very short. My grandmother didn’t like Dagenham at all, and returned to Oldham with my father after less than a year. Alfred Sr. remained in Dagenham for awhile, but then moved to Morris in Oxford before returning north to eventually work for Fairey Aviation in Stockport. I don’t know the timing of these moves, or the reasons for them, but he must have been back in Oldham by the middle of 1937 because my uncle was born in January 1938. It seems Fairey received a number of military contracts in the mid 1930s which encouraged the company to expand and, in 1935, acquire a large factory (the Willys Overland Crossley plant) in Heaton Chapel, Stockport from a company called Crossley Motors Ltd. (see Chapter 8 and Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History for information on both Crossley Motors and Willys Overland Crossley). It may have been with the expansion of the company that my grandfather saw an opportunity to return home, and came back north around 1935. By strange coincidence after my mother died I came across an old photograph of my grandfather and some of his friends in an old car that turned out to be a Crossley (see below). I’ve been informed by Malcolm Asquith from the Crossley Motors web-site that this is a 25/30 tourer with ‘Manchester’ body. This car was manufactured between 1919 and 1925. Amongst the same group of photos was another of the same chaps in a pre-1925 Austin 20.

My father had told me that his dad had owned an Austin, so I’m guessing that the Crossley belonged to one of his friends. When these photographs were taken is hard to know, but I would guess this was in the late 20s early 30s, probably before my grandad was married in 1931 – indeed this could have been on his stag do! The chaps certainly look a little worse for wear, and the Austin photograph looks like it is on the seafront.

Like my grandfather, his brother George Jr., his sister Annie and her husband Tom Shaw, and his other sister Ethel’s husband Charles Bailey, would leave Oldham to find work, in their cases in Birmingham. George would eventually return to Oldham, but Annie and Tom Shaw and Charles Bailey would remain in Birmingham. In the 1939 register both Tom Shaw and Charles Bailey are described as a fitters/erectors of steel wagons, and later in the record of his death in 1945 Charles is described as an engineer’s driller. Clearly, despite the downturn in the economy caused by the depression in the 1920s and 1930s, both the Thomas brothers and their sisters’ spouses had found useful employment in the engineering industry, and had weathered the storm by being willing to move to where work was available. I can’t help but feel that this situation is a reflection of an inherent Thomas family trait – firstly illustrated by the move of Edward and Ellen Thomas from North Wales to Chadderton around 1800, the shift of occupations of John and Joseph Thomas from the spinning mill to engineering in the 1850s, followed by Joseph’s emigration to America in 1869, my father’s cousin Jack’s emigration to South Africa in the 1960s, my father’s desire to move to Australia about the same time, and latterly my own experience during the Thatcher era, obeying Norman Tebbit’s advice to get on my bike and find a job – by emigrating to the USA!

Having survived the ravages of the 20s and 30s largely unscathed, the family now entered one of the most dangerous periods in its history – World War II. However, I want to leave that story for my final chapter (Chapter 8). Next I want to venture across the sea to examine my Irish roots.

The mythology surrounding George Vinge Thomas

If you’re still curious as to why George’s life acquired the mythology of his Welsh birth, rugby playing, bookmaking, etc., and don’t want to wade through the next few chapters, you can skip to the Epilogue to discover why.