“When you are again exhorting a suffering people to fortitude under their privations,…may God grant that by your decision of this night… that such calamities…have not been aggravated by laws of man…” — Robert Peel, Tory politician and British Prime Minister (1841-46)

“…a famine of the thirteenth century acting upon a population of the nineteenth…” — Lord John Russell, Whig politician and British Prime Minister (1846-52 and 1865-66)

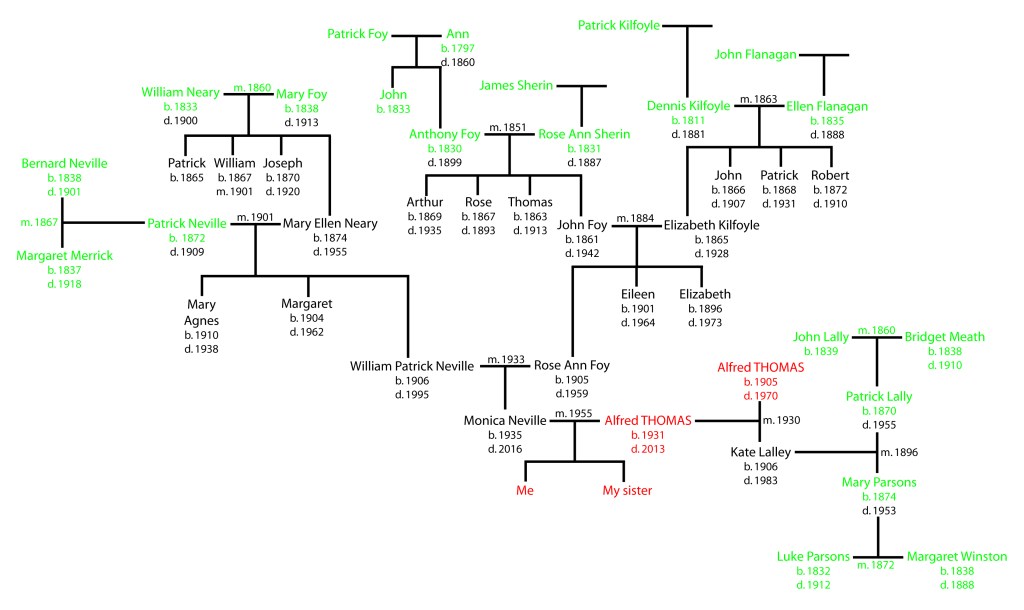

In this narrative I’ve concentrated upon my paternal ancestry, and as such my Celtic heritage, despite my surname, is somewhat tenuous – being limited to two individuals from Wales, seven generations back. Nevertheless, my genetic ancestry is certainly more Celtic than Anglo-Saxon. This is due to both my maternal forebears and my paternal grandmother’s heritage being almost entirely Irish. Effectively, I have a quarter English-Welsh blood and three-quarters Irish.

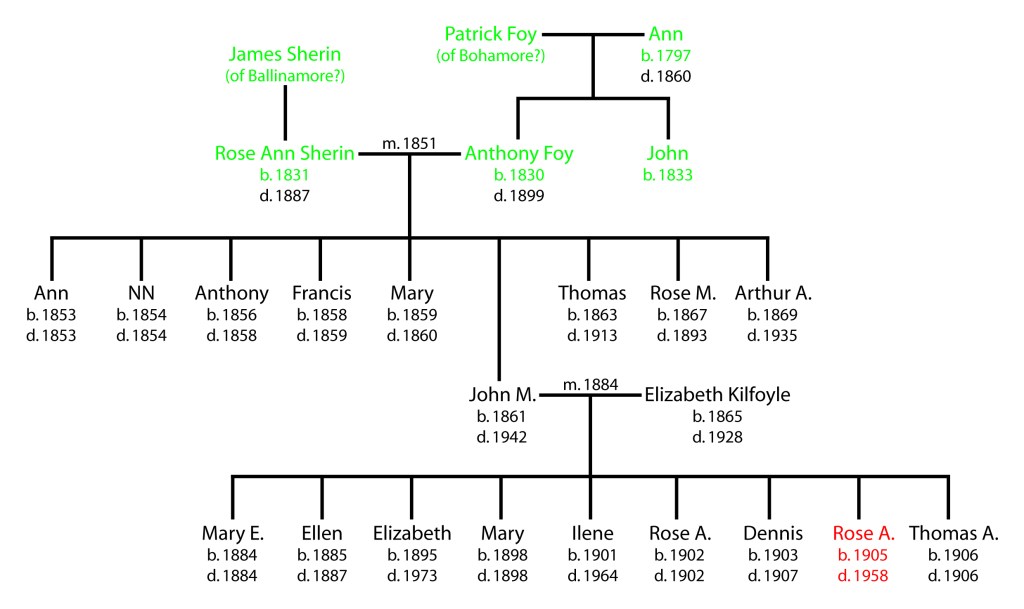

The first of my Irish ancestors to come to England were the Foys and Kilfoyles that make up my mother’s maternal lineage (see the family tree, below). Sometime a little before 1851, two brothers Anthony and John Foy arrived in Wakefield with their mother Ann. In February 1851 Anthony would marry another Irish immigrant, Rose Ann Sherin, in Wakefield Parish church. The Foys and Rose Ann must have left Ireland in the mid to late 1840s, the logical assumption being that they were driven to emigrate by the Great Famine.

Historically the English have been characterized as unfeeling tyrants who were responsible for the deaths of a million poor Irish citizens, and the forced emigration of another million people. Although it cannot be denied that the British government was complicit in these tragic events, the story is not as simple as it seems. As the quotes above show, there were men in the ruling parties who were cognisant of, and sympathetic to the hardships of the Irish poor. Nevertheless, the response of the government was totally inadequate, mainly due to an arrogant attitude of some officials (e.g., Charles Trevelyan) who believed that the famine was a result of divine Providence sent down upon an undeserving people. As a result, the prevailing attitude amongst the absentee landlords and some Westminster politicians was that any aid should be given only to those willing to work for it. Indeed Treveleyan would say of the Irish “…the selfish and indolent must learn their lesson so that a new and improved state of affairs must arise…”. Such attitudes were compounded by the political manoeuvrings of some Irish Nationalists who wanted “…no begging appeals to England…no feeding of our people with alms…For who could make…freemen of a nation so basely degraded?” (The Nation, 8 Nov 1845); of course, the ultimate aim of the Nationalists being a completely independent Ireland.

At the end of 1845 beginning of 1846, the Prime Minister, Robert Peel, would buy maize from America (enough to feed 500,000 people for three months) and suspend the Corn Laws to allow cheaper imports, but such measures were totally ineffectual in the face of the year-on-year failure of the potato crop. The belief that the Irish poor must do something in return for British benevolence dominated government thinking, and led to the introduction of a programme of public works. This policy gave work to over 700,000 people, however the rates of pay were pitiful and did very little to prevent people starving to death. One can understand why many Irish believe the famine was akin to genocide caused deliberately by the British government. Nevertheless, despite an economic depression, a collection from the English people raised £435,000 (over £35 million today), the British Relief Association helped to feed up to 200,000 children, and a further £9.5 million in aid was provided by the Government – but even such help wasn’t sufficient. So rather than starve the Foys and Kilfoyles, like many others, travelled across the Irish Sea to England.

The Foys

According to Anthony’s marriage registration in 1851, his father was a farrier called Patrick; however, Patrick is not found in the 1851 British census, and Anthony’s mother is described as a widow in that same census, so presumably Patrick died before Anthony moved to England. Similarly, Rose Ann’s father was a farmer called James, but I’ve never been able to find her father or mother in the British censuses; so, either Rose Ann’s parents had already died, or she had left them behind in Ireland.

The exact origins of the Foy and Sherin families are difficult to ascertain. According to the 1871 census both Anthony and his wife, Rose Ann, were born in County Mayo. Using the 1901 Irish census, I searched for all male Foys between the ages of 20 and 40, and found 33 families in Mayo. These Foy families are found in different areas of the county, but there was a particularly strong cluster just to the east of Castlebar in the Electoral Divisions (EDs): Bellavary, Bohola, Breaghwy, Strade, Toocananagh, Toomore, and Turlough. Indeed of the 33 Foy families, I found 16 in this triangular area just south of Lough Conn between Castlebar, Bohola and Foxford.

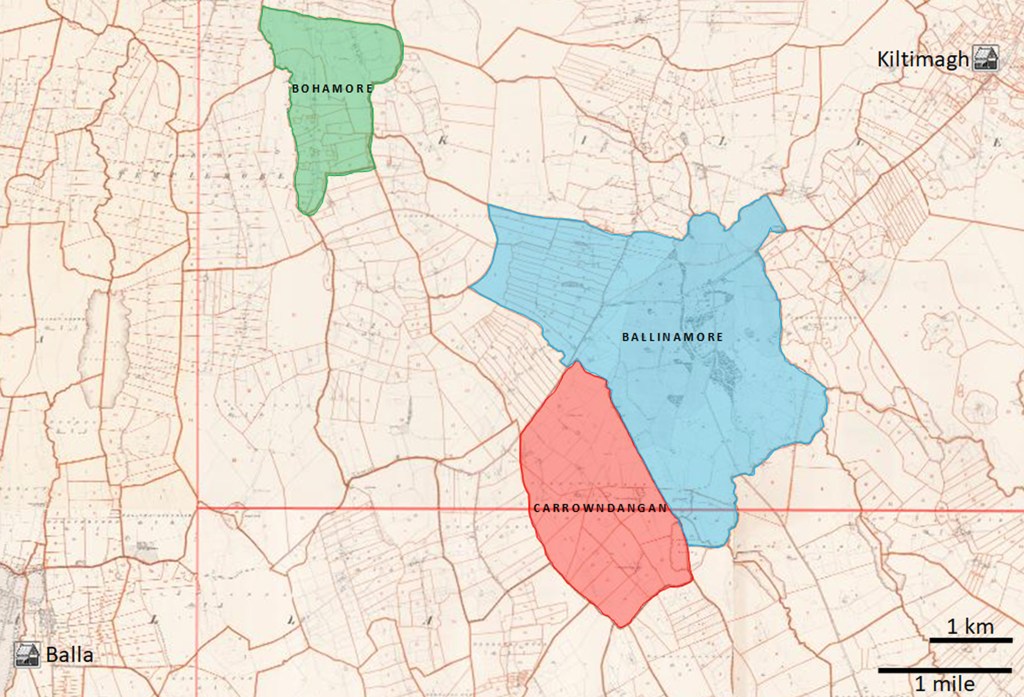

A similar analysis of the occurrence of the Sherin surname in Ireland revealed that this wasn’t such a common name, being mostly found in the west and north of Ireland with just two families in Mayo. However, the spelling of Irish names is notoriously varied, and another name, Sheeran, proved to be somewhat more prevalent. There were 10 Sheeran families in Mayo in 1901, with a cluster of seven families in the ED of Knocknalower close to the Atlantic coast and Broadhaven Bay. On the other hand, searching Griffith’s Valuation (1856; Ask about Ireland) I discovered two James Sheerans in Mayo. Both of these men were tenants in the Parish of Killedan (one in the townland of Ballinamore and the other in Carrowndangan; see map above). In an attempt to determine whether Anthony and Rose Ann may have been acquainted before emigration to England, I searched for Foys in Killedan and neighbouring parishes. The closest I could find were Patrick, Matthew and John Foy who all lived in the townland of Bohamore (Parish of Bohola). The map above shows the proximity of these townlands to one another. Anthony’s father, Patrick, would have been dead on publication of Griffith’s Valuation in 1856. This fact would tend to argue against the Patrick listed in Griffith’s valuation in Bohamore being Anthony’s father. Nevertheless, the presence of three Foys in Bohamore, and the proximity of Bohamore to Ballinamore could support the theory that James Sheeran of Ballinamore was Rose Ann’s father, that Anthony Foy originated in Bohamore, and that the couple knew each other before emigrating to England.

Just after Anthony’s marriage, the 1851 census shows that Anthony is a fish dealer, and in the next census this is still his occupation; however, he and Rose Ann are now living in Glossop, Derbyshire. A nephew, Arthur O’Brien, has accompanied them from Yorkshire to Derbyshire, but neither Anthony’s mother nor his brother are living in Glossop. The first of the couple’s children, Ann, was born in early 1853; so, the Foys must have left Wakefield some time between April 1851 and end of 1852. Ann would die soon after birth, and their next four children (three boys and a girl) would all die before the age of two. The first surviving child would be my great grandfather, John Mary Foy, who was born in November 1861.

It seems that Anthony’s mother had died in Wakefield in October of the previous year. Tragically, under Cause of Death on her death certificate is written “Found dead in her house probably from exhaustion caused by intemperance”. The certificate appears to suggest that whoever found her knew nothing about her other than her name. Age at death is given as “…about years…”, and Rank or Profession as “Widow of…”. The Wakefield Journal and Examiner reported on the 2nd November 1860 that “An inquest was held at the Borough Market Arms…on the body of Ann Foy…evidence showed that the deceased was of very intemperate habit, and was on Monday night so intoxicated that she had to be taken home by a policeman…discovered in the morning quite dead on the sofa in her room. Verdict – Died from natural causes.”. Clearly, both Anthony and John had left their mother behind in Wakefield, we may never know under what circumstances – did they leave because of her intemperance, or did she turn to drink after having been abandoned by her family?

In Glossop Anthony and Rose Ann would establish a successful fish-dealing business with a stall on the local market. I discovered several newspaper articles about the family and their business which appeared in the Glossop Record (GR) and the Glossop-dale Chronicle & North Derbyshire Reporter (GCNDR). One of these articles related Anthony’s prosecution for leaving a pony-drawn cart unattended on the turnpike (GR, Feb 1868), and another a notice advertising the sale of a piebald pony by Anthony (GCNDR, Aug 1881). Taken together these newspaper entries suggest that Anthony had a fish-dealing cart somewhat similar to those in the photos above.

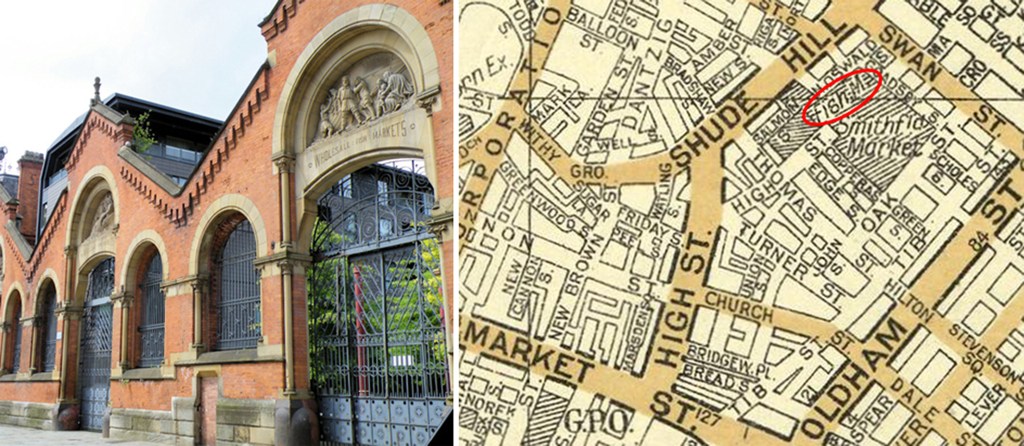

Yet another article reported that Anthony was suing the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway Company when they had sent a barrel of his fish to Mottram instead of to Glossop (GR, Nov 1860). This article gives some clues as to his business operations. He would have purchased fish at the wholesale fish market in Manchester and then used the railway to transport the fish to Glossop. Before 1873, the wholesale market for fish was the Victoria Market on Victoria Street near the Old Shambles and the Market Place (see map, below). Anthony would have purchased fish at the market and then transported his acquisitions to London Road Station (now Piccadilly), perhaps using a hand barrow. From London Road the fish would be transported to Glossop via a branch off the main Sheffield line from Dinting.

Some of the newspaper articles about Anthony and his family were not so flattering – once being accused of selling fish that were not fit for human consumption (GCNDR, July 1883)! Nevertheless on the whole Anthony appears to have become a respected member of the Glossop community, once appearing as a Juror in an Inquest into the death of an infant (GCNDR, Sep 1886), and in an article following his death (GCNDR, Apr 1899) being described as “…a well-known figure in the Glossop Market, having been a stall-holder for a period of about 40 years. He was of a jovial and kindly disposition.”.

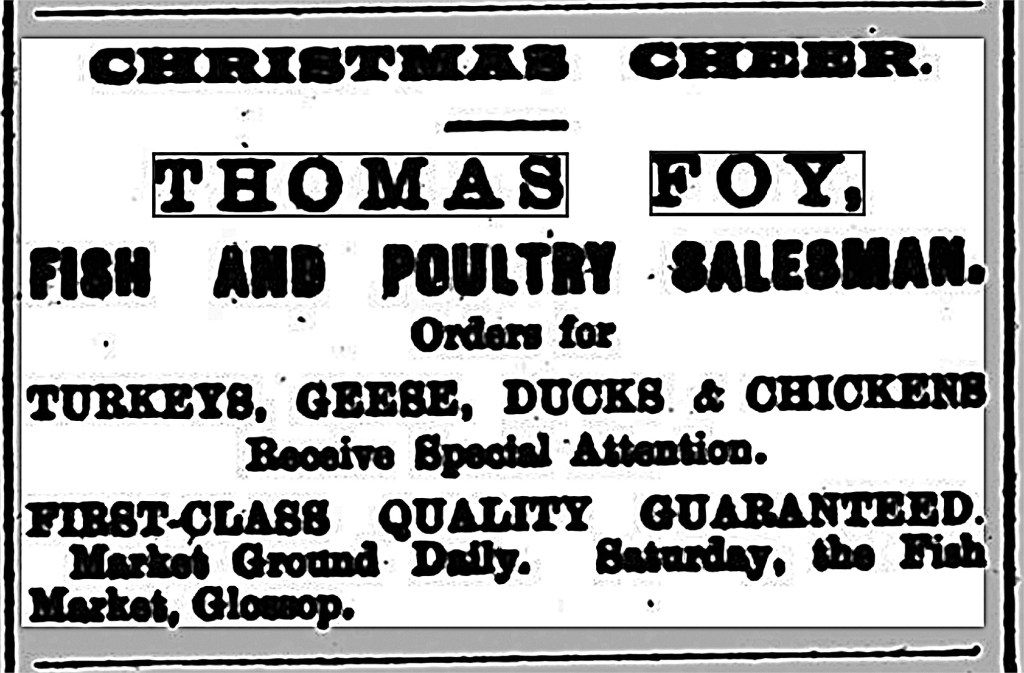

Following Anthony’s death, the business would be taken over by their younger son, Thomas, not the eldest son, my great grandfather John (see advertisement, above). Several other newspaper articles may go some way to explain this situation. One in May 1883 (GCNDR) reports that Anthony and John were summoned before the Magistrate for using “profane and obscene” language in a public place. Apparently a passing police constable heard John call his father “very bad names” and, in response, Anthony ordered his son out of the market “using the same kind of language”. When the policeman went and spoke to Anthony, he also used bad language to him. The defendants were each fined 5s and costs. In several other incidents reported in the newspapers John was prosecuted for fighting (May 1883), playing pitch-and-toss (Oct 1891) and running an illegal gambling game at the Peniston Agricultural Show Ground (Aug 1892). Indeed, my mother had told me that her grandfather was betting man, and perhaps this was the reason that Anthony didn’t want to leave his business in such untrustworthy hands. These incidents may also explain why John chose to move away from Glossop to Oldham around 1902 with his wife, Elizabeth and their two young daughters, Elizabeth and Eileen.

The Kilfoyles

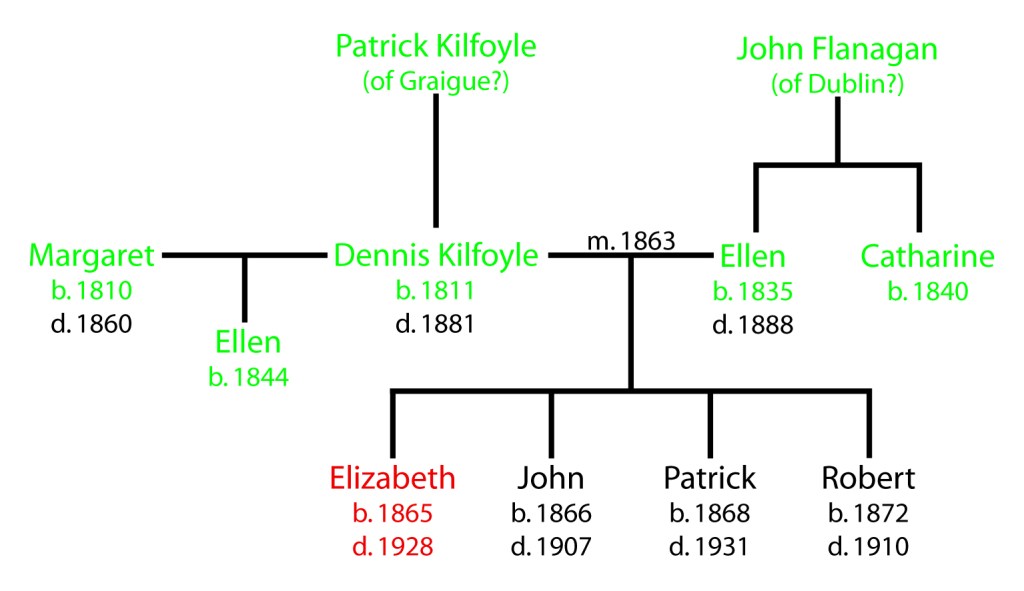

In 1884 John Mary Foy married Elizabeth Kilfoyle in St Mary Crowned RC church, Glossop. Elizabeth was the daughter of a Dennis Kilfoyle, a stoker at a mill (most probably cotton). I soon discovered that Dennis had married Elizabeth’s mother, Ellen Flanagan, at All Saints RC chapel, Glossop in 1863. Ellen appears in the 1861 census living with her sister Catherine in High Street, Glossop. According to their marriage record Dennis was also resident in the High Street, but initially I was unable to find him in the census. However, with the help of the members’ forum of the Manchester & Lancashire Family History Society (MLFHS), I eventually discovered the reason I couldn’t find him was due to a transcription error on findmypast (“Kilfoy” transcribed as “Kilpy”). When I viewed the census return, it showed that he was living on the High St with a daughter, Ellen, and that he was a widower. I would later find the death (in 1860) of his first wife, Margaret, and her burial in the grave that would later accommodate both Dennis (1881) and his second wife (1888). The daughter from his first marriage was born in 1844 in Ireland, so Dennis, Margaret and Ellen must have left Ireland sometime after 1844 but before 1860. Where in Ireland they came from I have not been able to discover. I can find no birth or baptism of Ellen Kilfoyle whose parents were named Dennis and Margaret, nor a marriage of Dennis and Margaret.

Searching Griffith’s valuation I found no Dennis Kilfoyles, but two Denis Guilfoyles in 1850. Both men were living close to Nenagh in Co. Tipperary in the townlands Graigue (Parish of Ballygibbon) and Pallas East (Parish of Templedowney; see map below). On the registration of Dennis’s second marriage to Ellen Flanagan it states that his father, Patrick, was an out-door labourer. If Patrick was just a labourer it’s unlikely he would have rented any land. Of the two Denis Guilfoyles in Tipperary, the one living in Pallas East rented a house with over 15 acres of land, whereas the one living in Graigue rented just a house. It would seem more likely that the latter Denis Guilfoyle could be the one who emigrated to Derbyshire.

Examination of the Tithe Applotment Books created a few years before Griffith’s valuation showed that the Denis Guilfoyle of Graigue was renting a house in 1848 that measured 28ft by 16ft 6in (or 462 sq ft) and was 5ft 6in in height. The property was classified as 3C+. The number three defining the house as being a “Thatched house with stone walls with mud or puddle mortar; dry stone walls pointed or mud walls of the best kind” (see The National Archives of Ireland). The letter C+ indicating the “quality” of the dwelling as “Old, but in repair”. Based on the quality of Denis’s house, a “value per measure” was assessed by the valuer as 3¼d (1.35p). A “measure” was defined as 10 sq ft, so the value of the house was 46 measures multiplied by 3¼d or 12s 5d (62p). This value was supposed to equal the annual income expected from the property; for a house, I imagine that this value would be equivalent to the annual rent. So perhaps, Denis was paying something like 3d (1.25p) per week in rent in 1848. The illustration below shows a typical Irish thatched cottage in Tipperary. Despite the passage of perhaps 200 years, such Irish cottages don’t appear much different than that rented by my ancestor John Dalton in Oldham in 1681 (see Chapter 1).

As stated above, Dennis Kilfoyle would marry Ellen Flanagan in 1863. According to the marriage register her father’s name was John, and in the 1881 census Ellen states that she was born in Dublin. The year of her birth from census returns is somewhat variable, but would be 1835 ± 5 years. However, I’ve been unable to find a birth or baptism of an Ellen Flanagan/Flannagan born in Co. Dublin whose father was called John in those years.

In 1901/02 Ellen’s daughter Elizabeth would move to Oldham with her husband John Mary Foy and their two daughters. There the couple would have four more children, only one of whom, my grandmother Rose Ann, would survive beyond three years. In Oldham John Mary would start his own fish-dealing business, being described as a fish salesman of 41 Lord’s Hill Square on Rose Ann’s birth certificate in 1905. Similarly, in subsequent censuses in 1911 and 1921 John is described as a fishmonger on own account or fish dealer, own business. In 1921 this business is described as having “no fixed place” – I would assume that he was a hawker with his own barrow similar to the ones in the illustrations, above. Whether he had a pony or used a hand-drawn cart is hard to know. In 1911, the family were still living in the town centre close to Lord’s Hill Square (Whiteley Street), but by 1921 they had moved out to the more rural area of Birshaw Hollow in Shaw. The latter location may have given John the facility to stable a pony or donkey. Like his father, John would probably have bought fish from the wholesale market in Manchester which, by this time, had moved to the High Street as part of Smithfield Market (see below). Again like his father, he would have shipped the fish to Oldham/Shaw using the railway, in his case from Victoria Station.

Interestingly, in moving to Shaw, John would become a close neighbour to his younger brother, Arthur Anthony, who had moved to Oldham Road, Shaw around the same time as John had left Glossop.

In 1921 all three of John’s daughters, Elizabeth Jr., Eileen and Rose Ann were working in cotton mills; although, Elizabeth is described as an “out of work” ring spinner at the Cape Mill (Refuge Street, Shaw). By this time, Elizabeth is married to Thomas Bell, and is living in Birshaw Hollow with two daughters, Eileen and Elizabeth. In 1921 Eileen Foy is not yet married, but she is a boarder in the house of the Keane family whose son, Andrew, she would marry in 1923. Eileen is working in the cardroom of the Woodstock Mill on Meek Street in Royton. Rose Ann, too, is employed in the cotton mill (a ring doffer at Beal Mill, Shaw), and is still living with her parents in Birshaw Hollow. By 1933, Elizabeth Sr. had died, and Rose Ann and her father had moved to Palmerston Street (off Lees Road). That year Rose Ann would marry my grandfather William Patrick Neville at St Ann’s RC church on Airey Street, Greenacres.

The Nearys

Compared with the Foys and Kilfoyles, my great grandfather Patrick Navil or Neville was a later arrival from across the water. The first definite record I have of him in England is his marriage to Mary Ellen Neary at Our Lady of Mount Carmel and St Patrick’s RC church on Foundry Street in 1901. Patrick’s wife had been born in Oldham, but her parents William and Mary Neary, like Patrick, had originally come from Ireland.

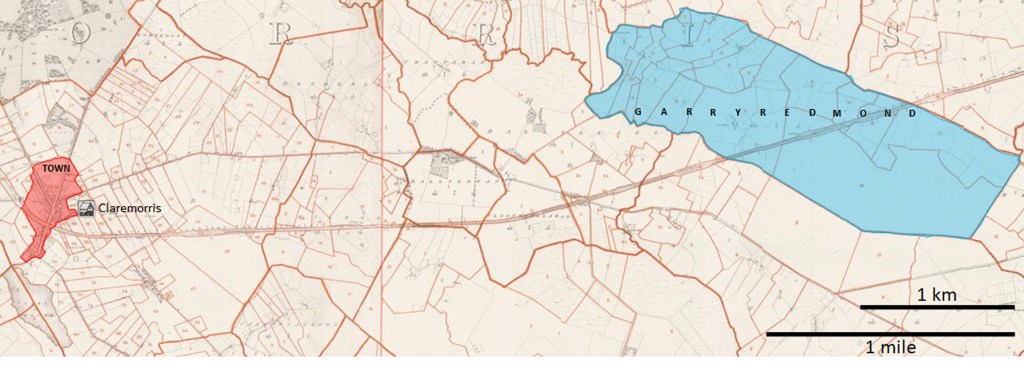

In the 1891 census, both William and Mary claimed to be from Claremorris, Co. Mayo. In the records of their children’s birth it is stated that the mother’s maiden name was Foy. Later I was to discover the marriage of William Neary to Mary Foye in Kilcolman parish which encompasses the town of Claremorris. The marriage register doesn’t give the names of the parents of the bride and groom; however, the witnesses to the marriage were John Lynsky and Bridget Foye. I would guess that Bridget was Mary’s sister, and that John was a good friend of William. As with others of my Irish ancestry, I searched in Griffith’s valuation for evidence of the Neary and Foy families in the vicinity of Claremorris. These searches revealed a John and a Michael Foy in the townland of Garryredmond to the east of Claremorris, but still within the parish of Kilcolman. I also found a Laurence Nary and a John Lynskey both living on Bridge Street in the town of Claremorris. Looking at the Tithe Applotment House Book of 1841 revealed that John Lynskey was a publican whose property included a “back kitchen, turf house and stables”. I wonder whether Laurence was William’s father, and perhaps, William was a regular at John Lynskey’s pub! It seems a little unlikely that this John Lynskey is the witness to William’s marriage, but could be the witness’s father.

The map, below, shows the proximity of Garryredmond to Claremorris. If Mary Foy had lived in Garryredmond, it’s likely she would have attended the parish church of St Colman on Chapel Street in Claremorris, and if William lived in the town it would also have been his church. A church where they may have first met, and the church where they were married in 1860.

When the couple arrived in England is hard to determine. They do not appear in the 1861 census, or in the 1871 census even though the births of five of the couple’s children are recorded in Oldham between 1863 and 1870 – a sixth child, my great grandmother, Mary Ellen Neary being born in 1874. It’s very easy to understand the motivation for the exodus of Irish people from the island in the late 1840s and the early 1850s as a result of the Great Famine. It has been estimated that about 1.25 million people emigrated to America between 1847 and 1852. Additionally, substantial numbers must also have moved to Britain; e.g., the Foys and Kilfoyles. Nevertheless many people, especially single men, but also women and some married couples, continued to leave Ireland throughout the later half of the century – around four million between 1852 and 1921 (see Kennedy, 1995). So, despite the fact there was no longer a famine, the Nearys were in no way exceptional in their decision to come to England in the early 1860s, likewise Patrick Neville’s move to Oldham around the turn of the century.

The Nevilles

In the record of Patrick Navil’s and Mary Ellen Neary’s marriage it states that Patrick’s father was Bernard, a farmer. Using the Irish Genealogy web-site I was able to find Patrick’s birth in July 1872 to Bernard and Margaret (formerly Merrick) in the townland of Roos, parish of Kilcommon, Co. Mayo. In the Griffith’s Valuation of 1857 in Roos a James Navel (Navil/ Naville/Neville) was living in a house with a Valuation of 10s, perhaps a rent of 2.3d (1p) per week. As well as the house, James also rented almost 24 acres of land. I think James Navel and Patrick’s father Bernard are probably related, but I’m not sure how. James could be Bernard’s grandfather, uncle or brother. I can’t be certain, but the property rented by James in 1856 may well be the property occupied by my Neville family ancestors in 1901.

In the census of that year, the cottage in Mayo occupied by my great, great grandparents was classified as second class, it consisted of stone/brick walls with a thatched roof, had three windows in the front, and two rooms. This cottage was occupied by five adults, my great, great grandparents (aged about 60) and three of their children (aged 19 to 26). The property also had a stable, a cowhouse and a barn. By 1911, the quality of the cottage had been reduced to third class and had only two windows at the front. There was also a cowhouse and a piggery on the property, and the house was occupied by seven people – Bernard Sr. had died by this time, but one son (Bernard Jr.) had married and was living in the house with his wife and two children (aged 4 yr and 2½ yr), as well as his mother, brother and sister. This cottage may also be the same property shown in the photograph, below, taken during a visit by my mother and grandfather to his cousins in the 1970s.

In the records of the births of his children, Bernard Sr. is variously described as a farm labourer, farmer and landholder. During the famine many tenant farmers had been evicted from their land due to their inability to pay their rents. To try to avoid a recurrence of this situation, the British government passed the Landlord and Tenant Act 1870. The act gave tenants much more security, including being compensated for any improvements that they had made to the property when they surrendered their lease. They would also be eligible for compensation if they were evicted for any purpose other than failing to pay the rent. In addition, the Act included clauses that had been proposed by John Bright to try to encourage the transfer of land from the landowners to the tenants. These clauses stated that the government would provide mortgages to the tenant to cover two-thirds of the cost of the property at an interest rate of 5% for a term of 35 years. However, fewer than 1,000 tenants took up the offer to purchase their farms. Indeed, in the middle of the 1870s things again turned bad for the Irish tenant farmers – the market was flooded with cheap grain from America, and a wet summer in 1877 led to further failures of the potato crop. Evictions from properties began to increase again forcing the government to revisit the laws governing rented property in Ireland. In 1880 an investigation into the workings of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1870 was undertaken – the Bessborough Commission. The report of the commission found that the effect of the 1870 act was minimal and that further legislation was required to achieve: fair rents, free sale, and fixity of tenure. As a consequence the government passed the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881. Although some reduction in rents occurred following passage of the act, there were still major problems and little transfer of property from landlords to tenants. It wasn’t until passing of the Ashbourne Act (Purchase of Land (Ireland) Act 1885) that significant numbers of tenants were able to purchase their farms. Over 25,000 farmers bought their homesteads between 1885 and 1888, taking advantage of the offer of government-provided, 100% mortgages at 4% over 49 years. This programme would cost the Exchequer about five million pounds, an amendment to the act provided another five million pounds in 1888, and other acts and amendments between 1887 and 1896 delivered another £33,000,000 for land purchase. Amongst the properties sold to tenants were those of bankrupt landowners – about 1,500 estates amounting to 47,000 holdings. It is interesting to note that the Mount Jennings estate that included the property rented by the Nevilles in the 1850s came up for sale in 1886, but the estate went unsold due to lack of interest. Following further acts of Parliament in 1903 and 1909, over 300,000 tenants managed to buy their land (11.5 million acres out of about 20 million acres in total in the country).

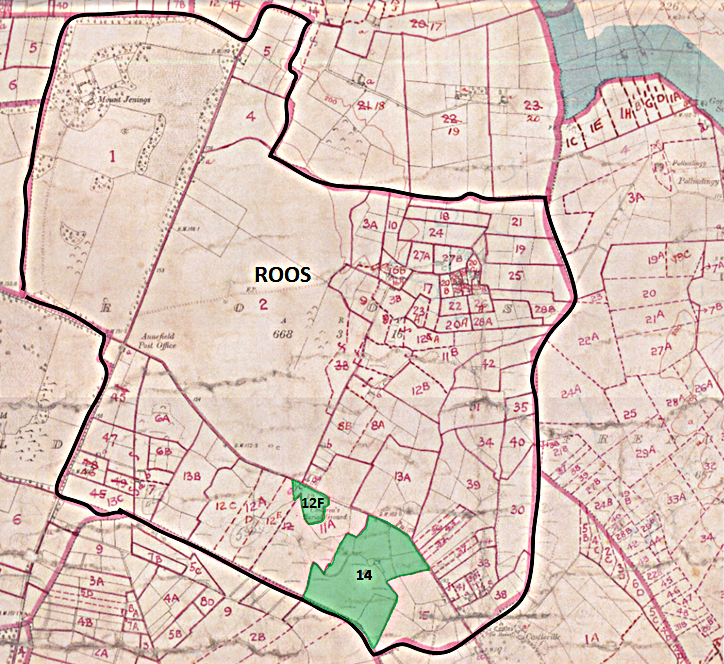

The Neville family did ultimately manage to purchase their smallholding. Records held by the Irish Valuation Office revealed that sometime between 1883 and 1895 a Patrick Navil became the owner of a house with outbuildings and 23 acres 3 roods and 29 perches of land in Roos (labelled 14 in map, below; note: the acreage is similar to that occupied by James Navel in the 1857 Griffith’s Valuation). Patrick appears to have obtained the property through a “Land Act Purchase”. I’ve no idea how Patrick Navil is related to Bernard Sr., it’s possible he was the son of the James who appears in Griffith’s Valuation (see above), and perhaps Bernard Sr.’s brother or uncle? However, in 1895 the ownership of the property was transferred to Bernard Sr.’s wife Margaret, and in 1926 to their son, Bernard Navil Jr.. In 1941, Bernard would add another nearby plot of land measuring 2 acres 2 roods and 28 perches (labelled 12F in map, below), making a total of 26 acres 2 roods and 17 perches. In 1955 the two properties were officially amalgamated and the land assessed at a combined, rateable value of £10, with the buildings valued at another 10 s. The farm is shown in a map of Roos from the 1920s below (highlighted in green).

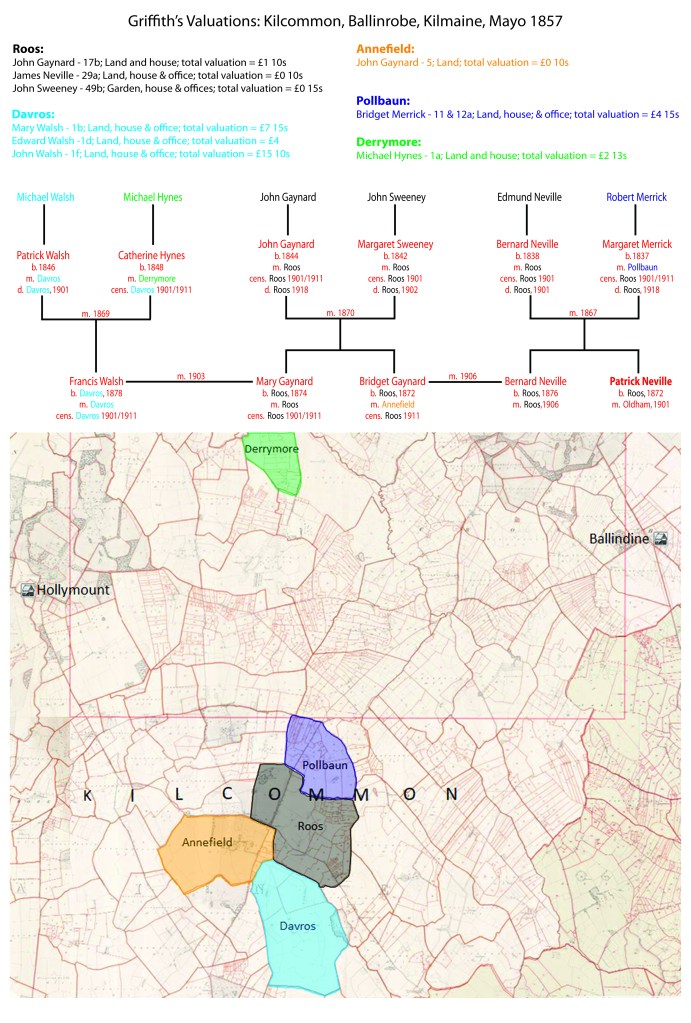

In researching the Neville family of Roos, I discovered that Bernard Naville and Margaret Merrick were married in the Parish of Kilcommon in 1867. At the time of their marriage, Bernard was living in Roose (or Roos) and Margaret in the neighbouring townland of Polbawnbeg (or Pollbaun). The marriage record states that Bernard’s father was named Edmund and Margaret’s father was called Robert. I’ve found neither Edmund Naville/Navel nor Robert Merrick in Griffith’s valuations in their respective townlands; however, I did find a Bridget Merrick in Pollbaun. It’s possible Bridget was Robert’s widow and Margaret’s mother? The only Naville I could find in Roos is the one mentioned above, James Navel – perhaps, Edmund’s father or elder brother?

However, in later records of the Hollymount Petty sessions of 1877 I discovered a Bernard Navil of Mount Jennings, Roos. He appeared to have been accused by a Daniel Dolan of not paying the sum of £1 2s 2d for “Goods sold”. Interestingly, Mount Jennings was the estate of the Jennings family and at the time of Griffith’s Valuation it was held in fee by Benjamin Jenings who also owned the property rented by James Navel. Mount Jennings (house) was the family home of the Jenings family. The first to reside there was a George Jenings (1732-1822), but by 1856 Benjamin is the owner of the estate. Griffith’s Valuation indicates that Benjamin owned virtually all the land in the townlands of Roos, Pollbaun and Kilglassan, together with a small amount of land in Annefield his total holdings added up to almost 1,000 acres. I found the death of a Benjamin Jennings, bachelor and Gentleman, in 1873 at Sunnyside, Rossmailley (Westport), and in 1876 a Charles Bingham Jenings was in possession of the estate. When the whole estate was finally put up for sale in 1888 it covered 1,805 acres. At a later date (1902), the house was the birthplace of a famous Irish ballad singer called Delia Murphy, whose parents lived in the house until the 1940s. In the 1970s the roof of the house was removed and by 1995 the house was in ruins.

In further research, I discovered that Bernard’s and Margaret’s son Bernard Jr. had married a Bridget Gaynard in Kilcommon in 1906 when Bridget was living in another townland bordering with Roos called Annefield. In addition, I found Bridget’s sister Mary’s marriage to a Francis Walsh of the neighbouring township of Davros. Taking together these births and marriages with the information from Griffith’s valuations gives rise to the summary below showing the inter-related families and the places they lived in the parish of Kilcommon south of Hollymount and Ballindine.

When Patrick Navil left Roos and arrived in Oldham is not clear. He was not at home with his parents and siblings when the Irish census was taken in 1901, and he doesn’t appear in the UK census that was taken on the same day. His future wife Mary Ellen is living wth her parents at 25 Hopwood Street in Oldham on the day of the census (31st March). Barely a month later the couple are married with both giving their address as 25 Hopwood Street. It seems unlikely that they courted for only a month before getting married, so I assume Patrick was living in Oldham at the time of the census, but has been missed by the census taker. His occupation on the marriage certificate is given as “gas stoker”; perhaps, working at the Oldham Corporation Gas Works on Greaves Street. However, by the time of my grandfather’s birth in 1906 he is working as a “general labourer”. Indeed just three years later he would die in an industrial accident while working for Whitworth Whittaker & Co. a builders and contractors on Rochdale Road. The Oldham Chronicle of the 31st July 1909 would report his death with the headline: “Blasting accident: Incautious Oldham man’s fatal injury”. According to the report, a gang of workers, including Patrick, were blasting rock with gelatine to create a reservoir at the brickworks on Rochdale Road on the 6th July. The men had set the explosive, lit the fuse and then retired to cover. Normally it took about six minutes for ignition to occur, but in this case there was a significant delay. Witnesses said that Patrick then came out of cover to investigate the problem, but then the gelatine exploded and Patrick was hit by flying rocks. He was taken to the Infirmary, but it appears an injury to his back became infected, and three weeks later he died of blood poisoning (sepsis).

My mother said that following his death, Mary Ellen received a small pension from Whittaker’s, but life must have been very difficult with two young children to look after, and being pregnant with a third. Indeed, my mother also told me that her father often had to go to Oldham Edge to gather coal for the fire. Just two years after Patrick’s death, the 1911 census shows that Mary Ellen’s mother is also living with the family as well as her brother, Joe – making three adults and three children in a household supported by only a single working man. However, in 1913 Mary Ellen’s mother, Mary Neary, would die bequeathing £26 2s to a pub landlady! In today’s money £26 might be equivalent to £1,300 (see the National Archives currency converter). This would suggest that, in addition to Joe’s earnings, Mary Ellen’s mother may have been making a significant contribution to the household income. However this bequeath also raises a couple of questions.

One, where did this money came from? My mother said that, when the Neary family lived in Water Street, they ran a small boarding house. In the 1881 census they have two lodgers staying with them, both of whom were born in Ireland. I suspect that the Nearys provided a temporary home-from-home for immigrants from across the water rather than a full-fledged boarding house. Nevertheless, such an arrangement must have brought in extra money to supplement the earnings of Mary’s husband, William, a general labourer.

Secondly, why did Mary leave a considerable sum of money to a Mary Ellen Nicholson the landlady of the Sir Ralph Abercrombie pub in Great Ancoats Street, Manchester, but nothing to her children?

Joe would die in 1920 leaving the family to be supported by the earnings of the elder children, Margaret and my grandfather, William Patrick, just fourteen but working as a little piecer at the Granville Mill in Derker. By 1921, his sister would be working in the cardroom at the same mill. The Granville was a spinning mill with 95,220 spindles (see Grace’s guide; and Gurr & Hunt, 1985) with machinery manufactured by the local firm of Asa Lees (see Chapters 5 and 6) and an engine built in the town by Buckley & Taylor (see Chapter 8). A few years later the youngest Neville, Mary Agnes, would also begin work and contribute to the family finances. However in 1931, Margaret would marry, as would my grandfather two years later, and then Mary Agnes in 1936. This would leave Mary Ellen alone with the income from the pension from Whittaker’s, assuming it was still being paid. She wouldn’t become entitled to a state pension until she reached the age of 70 (1944), and she wouldn’t have qualified for the Widow’s pension that had been introduced in 1925 because her husband had never contributed to the National Insurance scheme (introduced two years after his death). As far as I can determine, Mary Ellen never worked so it seems unlikely she would have made any National Insurance contributions of her own. On reaching age 70 she would have qualified for the so-called “non-contributory” pension of 5s a week (perhaps about £10/week today).

As mentioned above, my grandfather William Patrick Neville would be married in 1933 to Rose Ann Foy the daughter of John Mary Foy and Elizabeth Kilfoyle who were introduced at the beginning of this chapter. Two years later their only child, my mother Monica, was born. At the time, the couple were living in Bloom Street, but would later move to Richardson Street in St Ann’s parish close to the school that I would later attend from the age of four until I was 11. My grandfather would work in the cotton mill until being diagnosed with byssinosis, after which he would work as a gardener in the local cemetery at Greenacres.

The Lalleys

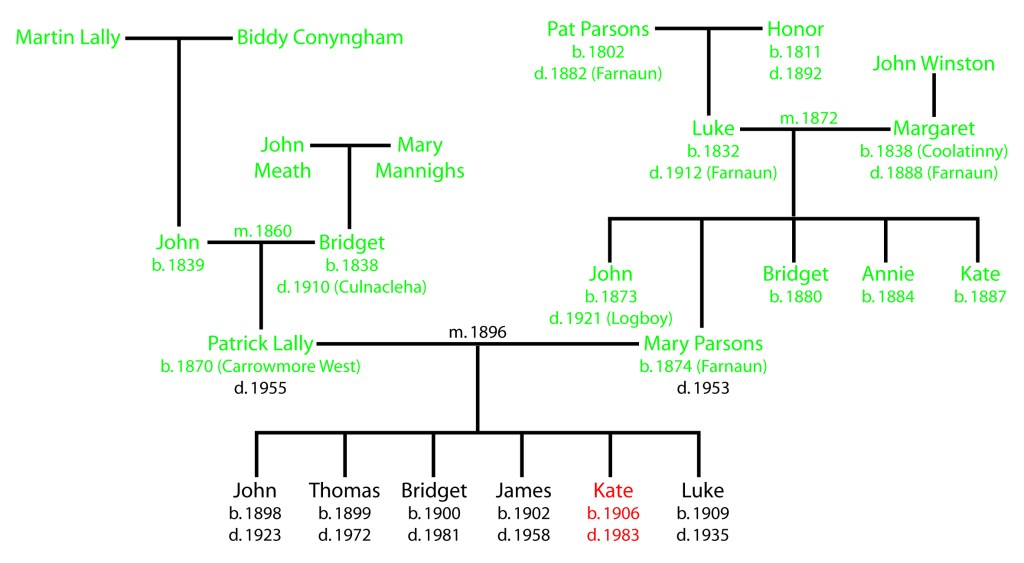

Having discussed all the Irish families that make up my maternal line, I’ll now turn to my paternal grandmother’s family. My father’s mother, Kate Lalley, was born to Patrick and Mary Lally (née Parsons) in 1906, the fifth of six children. Her parents had been married in 1896 at St Peter’s RC Chapel in Middleton. The first four children, John, Tommy, Delia (Bridget) and Jimmy, were born in Middleton, but Kate was born after the family had moved to Pine Street in Oldham. Three years later a sixth child would be born in Oldham, a son named Luke.

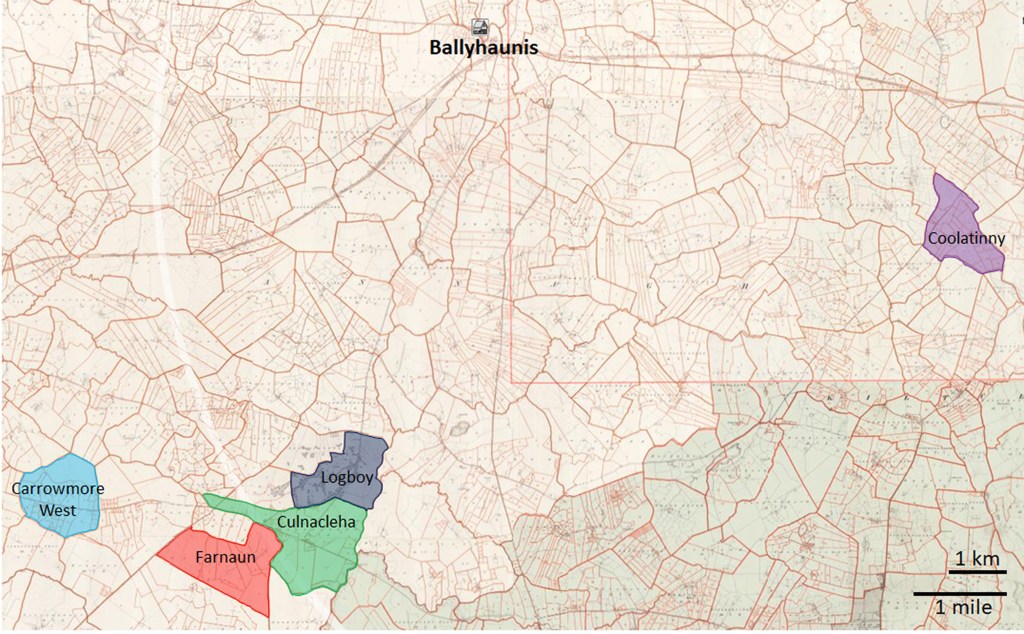

The record of Patrick’s and Mary’s marriage revealed that Patrick’s father was called John, and Mary’s father was a Luke Parsons. The couple both lived long enough to appear in the 1939 register, from which I obtained their dates of birth. With this information in hand, I was able to find both their births on the Irish Genealogy web-site. Patrick’s birth in 1870 was registered in the Registration District (RD) of Claremorris and the Dispensary District (DD) of Ballindine, the townland of his birth is given as Carrowmore. There are two Carrowmores in the DD of Ballindine, one in the parish of Crossboyne, and in the parish of Annagh there is the townland of Carrowmore West. Patrick’s parents were John and Bridget (née Meath), and their marriage is recorded in the parish of Annagh at Ballyhaunis in 1860. So, I suspect the most likely Carrowmore of John’s birth is Carrowmore West. Furthermore, although John and Bridget do not appear in the 1901 Irish census, Bridget’s death, at the age of 72 years, is recorded in the townland of Culnacleha just a few miles east of Carrowmore West also in the parish of Annagh (see map below). A year later John appears, aged 71, in the census in Culnacleha; he is living alone, a widower, in a 3rd class house of brick or stone with a thatched roof. The house has a single room and one window at the front, and has an associated barn.

Another piece of information that makes me believe that the Lallys lived in Culnacleha is a photograph that I found in the belongings of my grandmother after she died. This is a picture of two young women, perhaps in their early twenties, that has a short note written on the back. It was addressed to my great grandmother Mary Lally, it starts “My Dear Mrs Lally…” and ends “…with Best love to all from Delia Neary”. A little research revealed a Delia (aged 3) in the 1911 census living in Culnacleha with her parents John Edward and Mary Neary; and further investigation, the birth in 1908 of a Bridget, parents John and Mary Neary (née Hester) in the same townland. This photograph and its inscription suggest that my great grandparents may have visited Culnacleha and met Delia Neary – perhaps when Patrick’s father, John, died? The other thing of note, is that Delia Neary was born Bridget, and similarly my grandmother’s sister was born Bridget but always called Delia.

According to the 1911 census return, John Lally would have been born around 1840. As you might imagine John Lally is not an uncommon name in Mayo, and trying to determine where John was born is difficult. I’ve found a large Lally family in the townland of Sessiagh just to the south and west of Claremorris, but not a John of the right age. I discovered a John Lally born in Mayo in May 1840. This was not from a baptismal record, but a “search” of the 1841 and 1851 Irish census returns. Virtually all the census returns from 1841-1891 were destroyed in a fire during the 1922 uprising; however in 1908, when the census returns were still in existence, the British Government introduced a non-contributory pension scheme. In order to check the age of applicants in Ireland, the Government then carried out searches of the 1841 and 1851 censuses. The results of one of these searches, made on behalf of a Nora (or Honor) Lally in 1916, revealed a Lally family in the townland of Oultauns in the parish of Kilcommon on the border with Galway. In the 1841 census the head of the family was a Martin Lally (aged 32), his wife was called Winny (née Walsh, aged 27) and they had a son called John, aged 1 yr and 1 month. So, the right age, but geographically far from the site of John’s and Bridget’s marriage (Ballyhaunis), the birth place of Patrick (Carrowmore West), or their home in later years (Culnacleha) – all in the Civil Parish of Annagh.

The interesting thing about the Lally family in Oultauns is that they appear to be renting their property from a John Meath (see Griffith’s Valuation, 1856). Of course, John’s wife Bridget had the surname Meath which raises the possibility that the John Lally of Oultauns married the daughter of his landlord, and this couple are the parents of my great grandfather, Patrick. However, why they would be married in Ballyhaunis would be a bit of a mystery?

I did find a baptism of a John Lally of the right age and closer to Annagh in the parish of Kilcolman on the 27th May 1839, as we’ve seen previously this parish encompasses Claremorris and areas to the north and east of the town, but not the south side. The parents of this John Lally were Martin and Biddy Lally (née Conyngham). The argument in favour of this John being Patrick’s father is that this town was also the place where a Bridget Meath was baptized in 1838 (parents John and Mary Meath, née Mannighs) – a date that would agree with Bridget’s age of 72 at her death in 1910. As well as the ages implied by these baptisms, the possibility that the Lally and Meath families attended the same church in Claremorris may support the idea that these two baptisms are the baptisms of Patrick’s parents. Nevertheless, the question then remains as to why the couple would be married in the neighbouring parish of Annagh rather than in Claremorris? I guess it’s possible that the Meath family moved from Kilcolman parish to Annagh parish after Bridget’s birth, but before Bridget’s marriage in 1860. However, I can find no Meath or Meade families in Annagh in Griffith’s Valuation. Basically, I’ve come to the conclusion that the origins of John and Bridget must remain a mystery, mainly because of the paucity of census and birth records in this period in Ireland.

One strange coincidence is that the fathers of both John Lallys mentioned above are called Martin. Interestingly, I was able to find a Martin Lally of Claremorris as the recipient of a loan from the Irish Reproductive Loan Fund in 1847. Throughout the 19th century there were many local associations that provided small loans to the “industrious poor”. The loans were meant to provide seed money to men or women who were deemed to make good use of the money, and be able to repay the loans. Consequently, the borrowers had to provide two neighbours as guarantors, who would testify to their “honesty, sobriety and industriousness”. Martin’s loan had been provided by a large organization called the Irish Reproductive Loan Fund Institution administered in London. Although the Great Famine of the mid- to late-1840s is the most well-known, the Irish people suffered other serious famines due to the failure of the potato crop. One of these crop failures in 1822 was due to heavy rain damage to the crop in the previous season. As a result, a relief committee was set up in London that raised over £300,000 in assistance for the Irish poor. After the money had been distributed, there was money left over. Using about £55,000 of this residue, the committee set up a fund that would be used as a source of small loans for the poor in the counties of Clare, Cork, Galway, Leitrim, Limerick, Mayo, Roscommon, Sligo and Tipperary. The extent of loans that the Institute had to make during the Great Famine led to the demise of the fund in 1848, however many other smaller lenders would carry on making these types of loans into the early 20th century.

In January of 1847 Martin Lally borrowed one pound from the loan fund and paid the money back, with the addition of two shillings interest, over the next five months. The year of the loan was, of course, at the height of the Great Famine; however, Martin was clearly seen as reliable investment prospect, and suggests that he wasn’t one of the more desperate poor who frequented the soup kitchens and required charitable assistance. He was probably a small-holder, a tenant-farmer who needed a loan to buy animals or seed that would provide future income. However, Patrick’s father John is described as a farm labourer on Patrick’s marriage certificate. So, this Martin may not have been my great, great grandfather John’s father, or if he was, it seems that the tenancy didn’t pass to John, either because Martin had to give up the farm as a result of the famine, or because John was not the eldest son. The location associated with the loan is Claremorris. Even though this is the town where one of the John Lallys was baptized, it may just have been the administrative centre for the loans and the borrower could have been either of the two Martins discussed above.

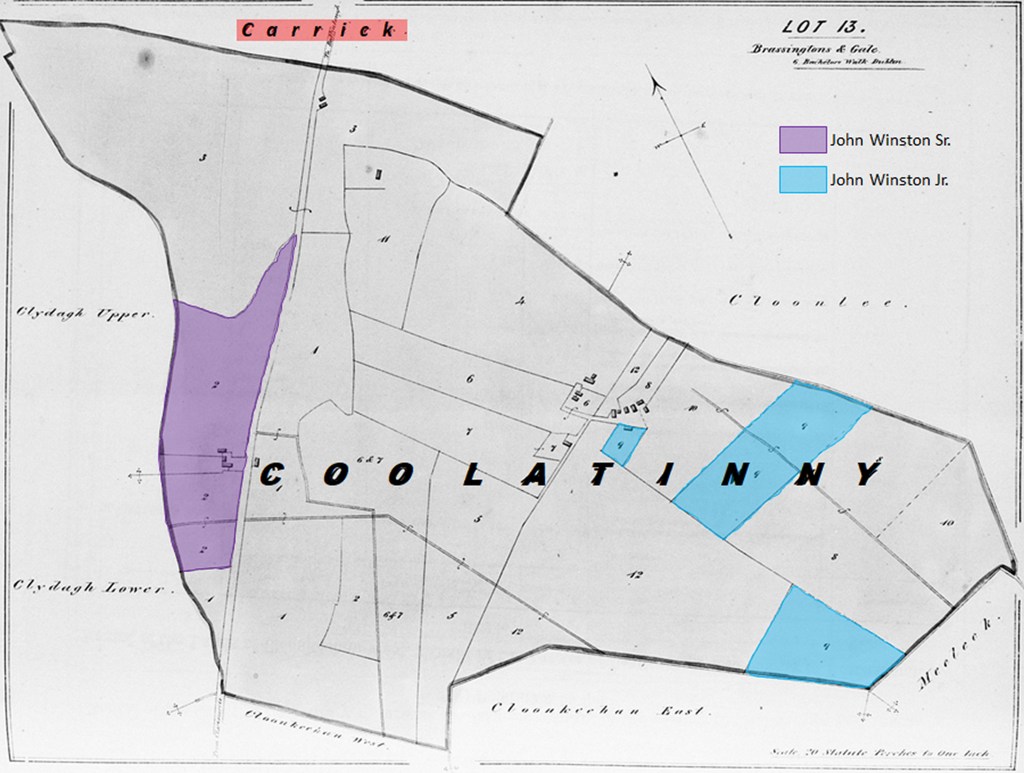

Patrick’s wife Mary Parsons was born in 1874 in the townland of Farnane (Farnaun; see map, above), Ballindine, Co. Mayo to Luke and Margaret (née Winston). Mary’s mother was actually born in the neighbouring county of Roscommon in the townland of Coolatinny, and Luke and Margaret were married in the Roman Catholic chapel in Granlahan (now Garranlahan), parish of Kiltullagh (RD of Castlerea). Margaret’s father was a John Winston and Luke’s father was called Pat. Both John Winston (Coolatinny, 1857) and Patrick Parson (Farnaun, 1856) appear In Griffith’s Valuation.

In Coolatinny, John Winston is renting a house and about 15 acres of land for £7 10s per annum. There is also a John Jr. (perhaps Margaret’s brother) who is renting a house and about 12 acres of land for £4 5s per annum. Both Johns rented their properties from Colonel Fulke Southwell Greville (later known as Greville-Nugent). Col. Greville was the MP for Longford from 1852 to 1856, again in 1857 to 1861, and for a third time between 1865 and 1869. In 1869 Greville was raised to the peerage as Baron Greville of Clonyn in Co. Westmeath, and served as the Lord Lieutenant of Westmeath from 1871 until his death in 1883. Interestingly, Greville’s property in Roscommon (the Kiltullagh Estate) came up for sale in 1858 under the auspices of the Encumbered (or Landed) Estates Court. This court was set up in 1849 to sell the property of those landlords who, due mainly to the affects of the Great Famine, could no longer afford the upkeep on their holdings. The court would sell off around 8,000 estates between 1849 and 1880. Clearly, Greville was a man of means, but it would seem his wealth was insufficient to support all of his estate, and he had to sell off at least some of his property. The whole of the Kiltullagh Estate amounted to almost 6,000 acres with an estimated value of £1,646 10s. In the records of the sale (available at findmypast.co.uk), both John Winstons, senior and junior, appear as tenants in Coolatinny renting properties of 15 and 13 acres, respectively (see map below). They both also rented fields in the neighbouring townland of Carrick (John Sr. renting another 15 acres, and John Jr. a half-share in a field of 25 acres with the widow of Thomas Winston). There are also several other Winstons listed as tenants in these two townlands: Patrick and Michael in Coolatinny; Thomas Jr., Patrick Sr., Patrick Jr., Lawrence and Michael in Carrick. How they are all related is hard to determine.

In 1856 in Farnaun, Patrick Parson is renting a house, a cottage and about 15 acres of land for £6 6s per annum. Patrick rented the property from Edward More O’Ferrall of Kildangan Castle, County Kildare. More O’Ferrall was one of the More O’Ferralls of Balyna House, Co. Kildare, the son of Ambrose O’Ferrall and half brother of Richard More O’Ferrall, who was the MP for Kildare (1830-47; 1859-65) and Longford (1851). Edward had acquired over 4,000 acres of land in Mayo, as well as a similar amount of land in Kildare and Meath on his marriage to Susan O’Reilly a descendant of Dominick William O’Reilly, Esq. a Catholic activist who had been a member of the Catholic Committee in the 1780s. This committee was formed to petition Parliament for “Catholic Relief” – attempts by Catholics to remove restrictions imposed on them following the Restoration of the Monarchy. Nevertheless, O’Reilly was one of the more conservative members of the committee, and followed Lord Kenmare as one of 68 members who seceded from the committee in a dispute with the more radical majority in 1791.

In contrast to the Lally family, Mary’s father and her siblings appear in both the 1901 and 1911 Irish censuses. The house is described as 3rd class and is a thatched cottage with two rooms. In both censuses one of the occupants is described as sick. Considering that Mary’s father, Luke, is 70 in 1901 and 80 in 1911 it’s most likely that he is the one with the illness. Indeed, he would die just nine months after the census in January 1912. It would seem that Mary’s brother John is running the farm which, in addition to the cottage, includes two out-buildings; in 1901, a stable and a piggery, and in 1911 a stable and a barn. However, on Luke’s death he would leave £2 10s to his daughter Kate, with John presumably inheriting the farm or tenancy.

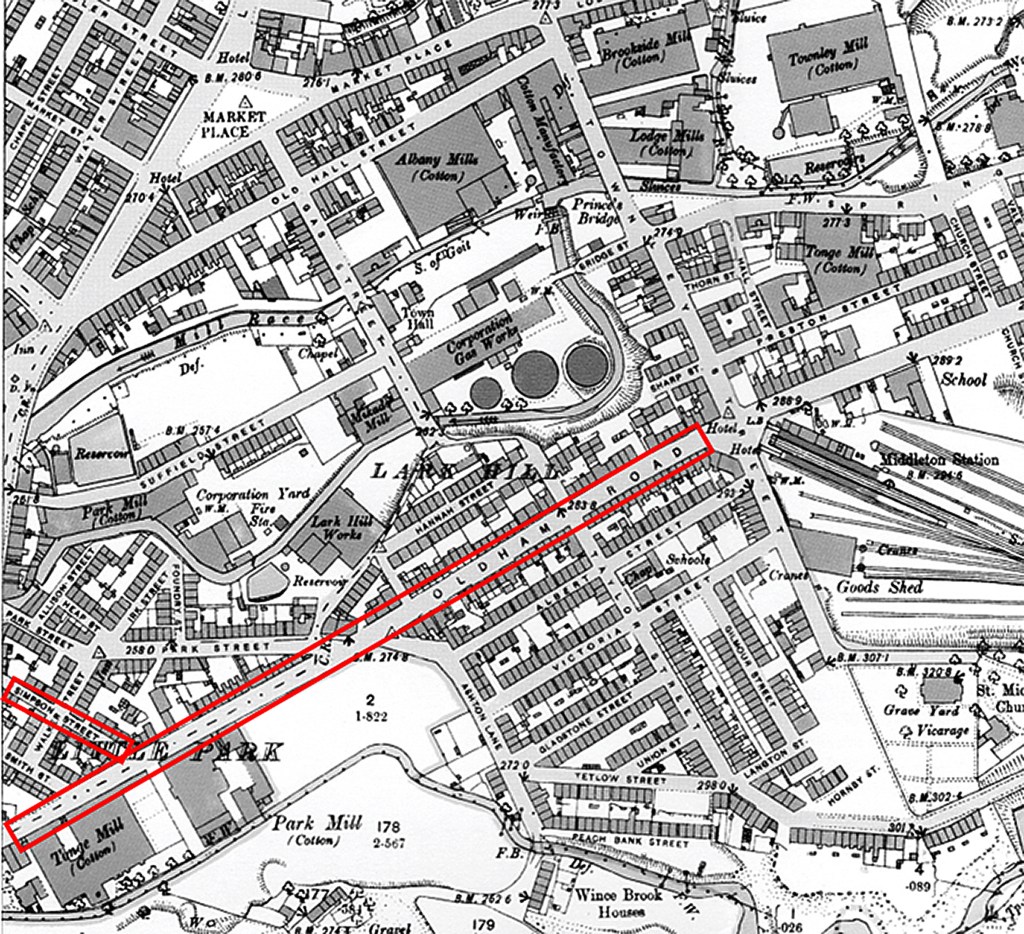

Farnaun where the Parsons lived is the neighbouring townland to the west of Culnacleha, where John and Bridget Lally were living in 1910-11, and barely a mile from Carrowmore West where Patrick Lally may have been born (see map above). Did Patrick and Mary know each other before they both ended up in Middleton? Perhaps, but we may never know. When Patrick and Mary left Ireland is difficult to know, the first record of them in England is their marriage in 1896, neither appear in the British census of 1891 so, presumably, they arrived sometime between 1891 and 1896. Their addresses on their marriage certificate show that they were close neighbours in Middleton, Mary living on Oldham Road at number three, and Patrick in Simpson Street at number nine. Examination of the 1891 census revealed that 3 Oldham Road was very close to the junction with Smith Street, and 9 Simpson Street close to the crossing of Simpson with Walker Street (see map from 1891, below).

In the record of their marriage Mary is described as a dairymaid, it’s possible Mary worked at the Home Farm Dairy adjoining Alkrington Hall which is a little south and west of the map above (on the other side of Wince Brook which can be seen running behind Tonge Mill). However, following their marriage, the couple would move to Fitton Street in the neighbouring district of Middleton Junction. Fitton Street is very close to Tonge Moor Farm, perhaps another place that Mary may have worked; but by the 1901 census Mary is no longer employed having recently given birth to the couples’ third child. Patrick was described as a general labourer on the marriage certificate, but in the census his occupation is bricklayer’s labourer, or hod carrier.

In 1902, the couple would have a fourth child (Jimmy) in Middleton, but sometime before my grandmother was born in June 1906 the family had moved to Oldham. A sixth child would be born in 1909 (Luke) giving rise to five adults, two teenagers and an 11-year old boy in 1921 living in a house that the census return describes as having just three rooms. In this census, Patrick is still described as a bricklayer’s labourer, my grandmother and her sister are both working in the cotton mill as ring spinners, Tommy is working as a carter for a cotton waste dealer (see Chapter 3), and the other two adult children (John and Jimmy) are unemployed carters. Just a couple of years later the eldest child, John, would die of tuberculosis at the age of just 25. In 1935 the youngest son, Luke, would die at the same age of another lung disease – acute lobar pneumonia.

At the outbreak of World War II, Jimmy would be drafted into the Army. Tommy, at 40, would probably have been too old, however he had previously been conscripted for the Great War in 1917 when he turned 18. He had been attested in May at Preston, and assigned to the 68th Training Reserve Battalion of the 16th Infantry Reserve Brigade (Training) – this was the training battalion of the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment. Nevertheless, within three months he had been deemed “no longer physically fit for war service” – paragraph 392 (xvi) King’s Regulations – and was discharged on the 10th August. The Army medical report states that this was due to “Bad Genu Varum” or extremely bandy legs – possibly a result of rickets. In contrast, Jimmy would be conscripted to the Army in 1941 and would serve his country for four and a half years, two and a half of those years in North Africa and Italy.

Jimmy Lally RA, 11252636

According to the 1939 Register, at the start of the war Jimmy was living in Crewe and working as a general labourer. His military record reveals that he was working for Wimpey’s, and being paid £3 per week. This record also states that he said that his main occupation was as a coal hewer in a coal mine – having previously been employed at Moston Colliery. However he also said that, after the war, he intended to go back to work in the building trade. Jimmy was conscripted in September and trained as a Gunner in the 213th Light Anti-Aircraft (LAA) Training Regiment of the Royal Artillery. In November, after training, he was assigned to the 302nd LAA Battery of the 95th LAA Regiment in Inverness. He would become part of a team operating a Bofors Anti-Aircraft gun (see illustration, above). He appears to have remained in the UK for another 16 months, perhaps in some coastal battery. At the end of March 1943 he was posted to “C” Battery Depot, probably in preparation for transfer overseas because in early April he was assigned to the X-List (iv) [see Army List table in Chapter 8], meaning he was in transit from Base to an active unit. On the 23rd April he could be found at the General Reinforcement Training Depot (GRTD) of the 1st Army in North Africa. On the 18th June he was assigned to the 49th LAA Regiment which was part of the 78th Infantry Division, commonly known as the “Battleaxe” Division because of its insignia. The 78th had been involved in the final battles of the war in Tunisia, including the Battle of Longstop Hill, but the war in North Africa was now over, and the Division was preparing to cross the Mediterranean to Sicily for the war in Europe. The Division had been part of the 1st Army, but the 1st would be disbanded, and the 78th join the 8th Army of General Montgomery. The 78th began transfer to Sicily at the end of July and would begin to arrive on the island on the 25th – just four days before Jimmy’s second transfer to the X-List (iv), suggesting he and his regiment were transported to Sicily around the 29th July.

Around that time (29th July-6th August) the 78th Division was involved in fierce fighting around the towns of Centuripe and Adrano in the shadow of Mount Etna. One would imagine that the role of the 49th LAA Regiment would be to protect the advancing British forces from any aerial attack by the Luftwaffe. Although in preparation for the invasion, which had begun on the 10th July, heavy Allied bombing had pretty much devastated any Axis aerial capability, with only two airfields remaining operational at the start of the invasion and over half of the Axis aircraft being evacuated to the mainland. Jimmy would have my wife’s father to thank for some of this advance bombing – Capt. Frank W. Cranz flying B-17s out of North Africa in several sorties over Sicily, and later Naples-Foggia and Rome-Arno.

On the 4th August, the 78th took Centuripe – a success that was greeted with astonishment by General Montgomery, and even led to a mention in the House of Commons by the Prime Minister. The fall of Centuripe pushed the Germans back to the so-called Etna Line; however, the 78th pressed on breaking through the line and capturing Adrano at the foot of Mount Etna just two days later. The Allied forces were now moving rapidly across the island – the Americans along the northern coast through Santo Stefano and Brolo, other British forces along the eastern coast through Catania, and the 78th moving through the central regions. On the 9th August the 78th would capture Bronte on the western flanks of the mountain, and two days later the Germans would begin their complete withdrawal from Sicily. By the 18th August the Axis forces retreat across the Straits of Messina was complete, with over 110,000 troops and their accompanying equipment escaping to mainland Italy.

The Allied invasion of mainland Italy began on the 3rd September with the British 8th Army (XIII Corps) involved in Operation Baytown and landing at Reggio di Calabria (on the toe of Italy). This was a diversionary tactic to draw Axis forces away from the intended invasion target (Salerno); however, as predicted by Montgomery, it failed because the Germans provided no resistance to the British and fell back to defend Salerno. Nevertheless, on the 8th September the Italian government surrendered and withdrew its troops, leaving the Germans to fight on alone. A day later the main invasion force under the command of U.S. Lt. Gen. Mark Clark began the primary invasion at Salerno – Operation Avalanche. However, the surrender of the Italian forces also opened up the possibility of unopposed landings on the heel of Italy at Taranto (Operation Slapstick). The 78th Division was held back to take part in Operation Slapstick as part of the British V Corps. Because of transport problems the landings at Taranto were much delayed, as a result the 78th Division only landed in Taranto on the 22nd September. The 49th LAA Regiment would remain part of the 78th Division and would continue fighting in Italy until the 6th November 1944, with the 49th finally being disbanded in January 1945. However, Jimmy would not be involved in the fighting in Italy. On the 6th September, Jimmy was subjected to a medical examination. His record seems to show that he was part of a Bofors gun team, but was taken out of the team due to arthritis. Although he’d not had a “medical board”, a local Medical Officer had downgraded him from A1 to B1 – “Free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service on lines of communication in Europe, or in garrisons in the tropics, able to march 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well”. In the ASC (Accredited Standards Committee) file, the PSO (Personnel Staff Officer) remarked that Jimmy “Suffers from Rheumatism and Arthritis, thinks sleeping in tents makes him worse. Says nerves are alright.” and “Seems strong and stable man and keen to get steady job. Not fit for exposed job due to arthritis.”. He then recommended Jimmy be given a job as an Office Orderly, or something similar. It would seem he spent the rest of the war working in the Central Mediterranean Force (CMF) HQ, and on discharge being described as “A very hardworking, sober and trustworthy soldier. His work here leaving nothing to be desired. I recc him for any Employment that requires Hardwork and Honesty.” – British Detachment HQ, Allied Commission, Italy CMF, 7th November 1945. Ten days later he was released to the Y-List (removed from active service), and in February moved to the Z-List (reserve). In 1947 he would be 45 and no longer available for recall.

As he had said in his statements to the Army, after the war Jimmy would work in the building industry. Photographs of him appear to show a lively, outgoing man with an easy smile, but perhaps it is a mistake to try to understand a person from a photograph. In 1958 Jimmy would commit suicide, drowning himself in the Rochdale canal close to Henshaw Bridge in Chadderton. According to his brother Tommy, in 1950 Jimmy had had an accident at work in a quarry when he was hit on the head from a falling rock. In December 1957 he had another work-related accident that meant he hadn’t been able to work for six months. At the beginning of June he had been certified fit for work, but he doesn’t seem to have found work. It appears he became very depressed by the lack of work, and the shame of having to sign on at the Labour Exchange – thinking that people looked upon him as lazy. He had tried to gas himself on Saturday, 28th June, however Tommy had returned home and found him before it was too late, and took him to the Infirmary. Nevertheless, this was just a temporary reprieve because on Monday he would go to Chadderton and drown himself. Tragically, 14 years later Tommy would do the same in exactly the same spot.

These sad stories bring to an end my narrative about by Irish ancestors, in the next chapter I will return to the Thomas family in Oldham to describe their experiences in the Second World War.