In the preface to his History of Oldham (1817) James Butterworth states “Custom hath established that every publication shall be ushered forth with some kind of preface…”; so in that spirit here is mine.

I had always been curious about my great grandfather, George Thomas. My father had been told by his father that George had moved to Oldham from Wales around the end of the 19th century to play rugby in the fledgling Northern Union. When I learnt about the launch of 1837online in 2003, I decided that this was my opportunity to discover whether the stories about my great grandfather were true, or not.

In my Preface I began with an epigraph that alludes to the difficulties in knowing precisely what is historically ‘true’. In a footnote in his book Troy, Stephen Fry states “The expectation that every last genealogical connection in a…dynasty could be known is asking too much…”. I expect many of you reading this document will have encountered a question about your family history that still remains a mystery after many years of research. So, this is my warning to you that some of what follows may turn out, with further research, to be incorrect.

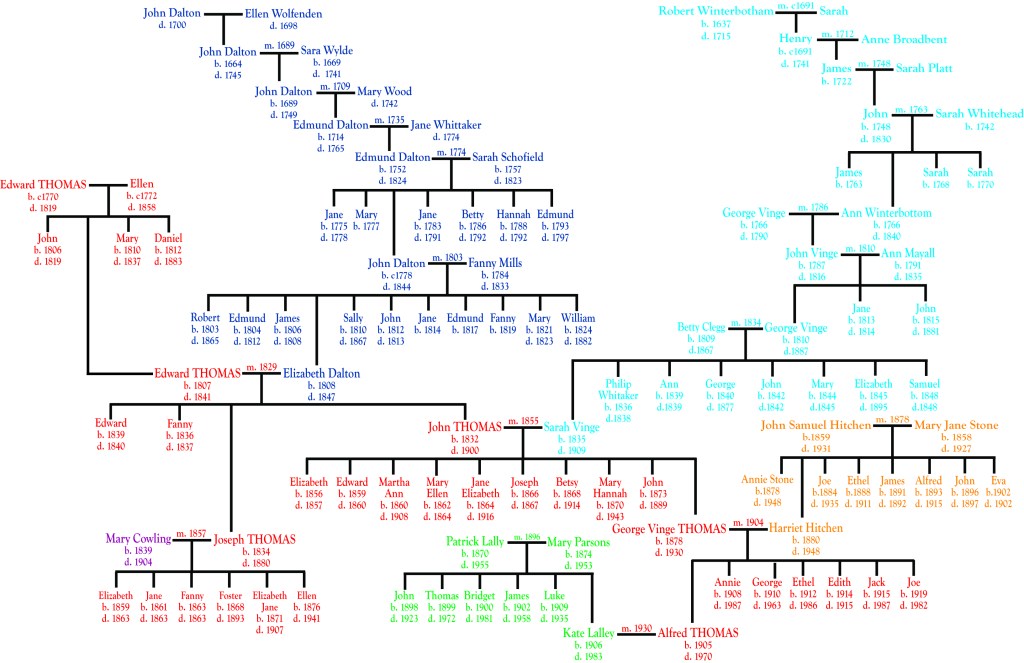

An illustration of the difficulties inherent in family history studies is the case of my great, great, great grandmother’s father John Dalton who you will encounter in the first chapter. In his Inns and Alehouses of Oldham 1714-1992 Rob Magee states that John Dalton, a hatter and seedsman, kept the Royal Oak on Rochdale Road, and that this same John Dalton later opened another pub, the Gardener’s Arms on Priesthill. However, my examination of christening records in Oldham revealed that there were at least four John Daltons living in the town at this time – two hatters, a spinner and a publican. The publican at the Royal Oak had a wife called Hannah and two daughters, Ann and Mary. In contrast, the 1841 census shows that the Gardener’s Arms in Cheapside (previously Priesthill) is being run by John Wood, the husband of Sally, and son-in-law of John Dalton (who is also resident at the pub). One of the hatters in the christening records has a wife called Fanny and 11 children, amongst whom one is called Sally and another Elizabeth (my great, great, great grandmother). On the death of Elizabeth, Sally and John Wood would take in Elizabeth’s two sons (John and Joseph Thomas; see Chapters 4 & 5). From these data, I’m quite confident that my great, great, great, great grandfather, John Dalton, was a hatter before later becoming a publican at the Gardener’s Arms, but that he didn’t run the Royal Oak. On the other hand, I also state in Chapter 1 that ‘my’ John Dalton was the hatter who was prosecuted and imprisoned for a combination in 1809. Nevertheless, I have to admit that I have no way of knowing whether indeed that is the case. It’s equally likely that the imprisoned John Dalton was the other hatter living in Oldham at this time.

I have tried to keep the narrative in roughly chronological order. So, the first chapter deals with the branch of my family tree (see below) that I’ve managed to trace back furthest in time. The chapter begins at the time of the Restoration (c. 1660) and follows the Dalton family line up to my great, great, great grandmother Elizabeth Dalton’s marriage to Edward Thomas, and the birth of their children around 1830. This chapter is the longest, both in length and in timespan (approx. 170 years). The second chapter covers Edward’s parents arrival in Oldham around 1800, and the division of the Thomas family into two branches, one in Hyde and the other in Oldham. The third chapter travels backwards in time again to the 18th century, to uncover the history of my great, great grandmother Sarah Vinge’s family line, including the marriage of her great grandfather George Vinge in Saddleworth Parish church in 1786, and the story of his wife’s family – Strinesdale clothiers by the name of Winterbottom. Starting from a Winterbottom will in 1715, this chapter ends with Sarah’s marriage to my great, great grandfather John Thomas in 1855, thus covering roughly 140 years. The fourth chapter takes a slight digression over the Atlantic with the story of John’s brother Joseph who emigrated to Philadelphia in 1869. However, chapter five brings us back to the Britain of Queen Victoria, whose reign (1837-1901) almost completely coincided with John’s life (1832-1900), bringing us to the end of the 19th century. In chapter six I deal with the chap who instigated this whole adventure, John’s son George Vinge Thomas. Chapter seven provides another digression, crossing the Irish sea to look at my maternal family line and the ancestors of my paternal grandmother. Finally (Chapter 8), I look at the lives of George Vinge Thomas’s children, focusing on their lives during the Second World War, and particularly my grandfather Alfred.

In setting down the results of my research in these pages, I have tried to put the history of my individual family members into the context of the prevailing social and political environment, both locally and nationally. In taking this approach, I hope to avoid the narrative becoming just a dry, chronological list of births, marriages and deaths, and to make the story more appealing to a wider audience. I hope you agree!

Paul Thomas – March 2022.