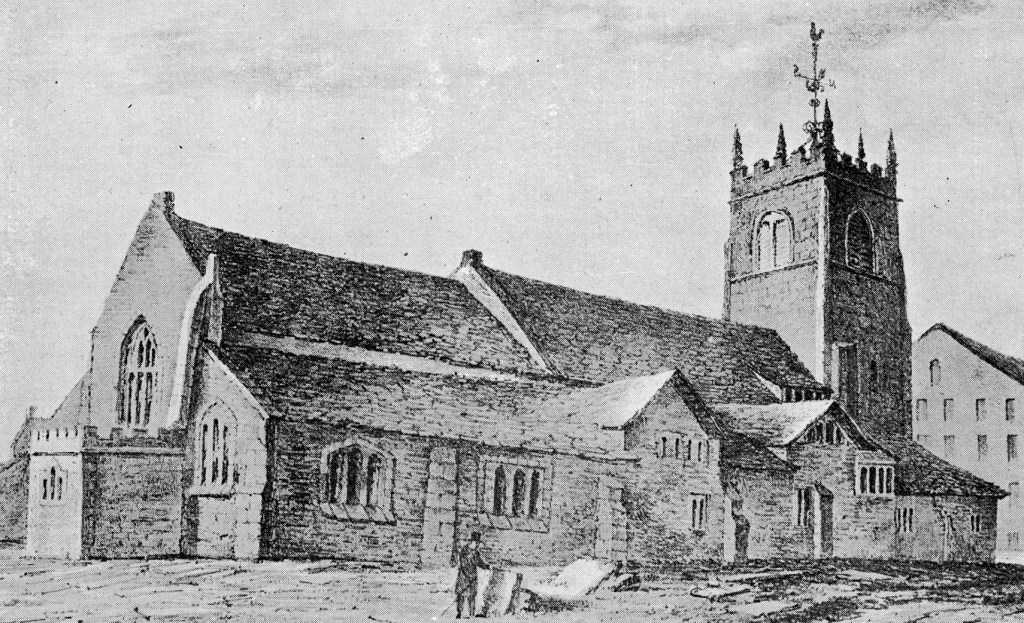

Several years ago when I began research into my family history, I came across records in Oldham Local Studies & Archives showing that several of my ancestors had been baptized in a non-conformist chapel called Greenacres Independent. Being raised a Roman Catholic, I was intrigued by this finding; so on my way home from the Archives, I decided to make a small detour via the chapel. On approaching the church graveyard I was struck by the fact that all the headstones were laid flat on the ground, many being completely overgrown by grass. However, in the middle of the central pathway was one large stone with some names still visible. I was surprised to see my own surname in the middle of the stone, and even more amazed to realize that here was buried the fifteen-year-old brother of my great grandfather! This finding began my fascination with the church and its history. The first non-conformist church in the town, founded by a minister ejected from the Church of England on St Bartholomew’s Day 1662. The Reverend Robert Constantine was the vicar of Oldham parish church (Fig. 1) [1] and this would be the second time he had been removed from his benefice. The first occasion being when he refused the Oath of Engagement at the culmination of the Second English Civil War.

The Oath of Engagement

In this article I aim to reveal how the English Civil War affected the lives of three men, two ministers and a merchant, each connected to the Parish of Oldham in Lancashire. What many think of as the English Civil War is perhaps more correctly termed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It was a prolonged period of conflict that consisted of the Bishops’ Wars in Scotland (1639-40), the First English Civil War (1642-46), the Second English Civil War (1648), the Irish Confederate Wars (1641-1653) and the Anglo-Scottish War (1650-52). As can be seen from the name of the first war in this series, the Wars of the Three Kingdoms was not just a political fight over the form of governance of Britain, but also a struggle over the type of national religion the populace should follow. It is this battle over the structure of religious practice that will be the central issue in this story, with the ministry of Oldham church providing an illuminating example.

Following its triumph in the Second Civil War, and the execution of King Charles I in January 1649, Parliament introduced an oath of allegiance to the new government that aimed to try to head off any further troubles across the country. The ‘Oath of Engagement’, as it was named, read:

“I do declare and promise, that I will be true and faithful to the Commonwealth of England, as it is now established, without a King or House of Lords.” [2].

The purpose was clearly to root out any Royalist troublemakers who might lead an insurrection against the new regime. Nevertheless, it proved a contentious issue even amongst those who were not necessarily allies of the Crown. The Act was first introduced in 1649 and was made obligatory for numerous ‘officials’ to sign, including ministers of the Church [3]. Despite the fact that Presbyterians had mostly backed Parliament during the wars, many ministers objected to the Engagement on the grounds of ‘conscience’; as explained by Edward Gee, a Lancastrian, Presbyterian minister [4]: “First, There is a weighty Case of Conscience, … as it is now imposed upon us … in way of Competition with, and opposition to antecedent religious Oathes, Vowes and Protestations … wee trust our close and continuall adhering to the first declared Cause … For King and Parliament … ingaged to in the Protestation, and the Solemne League and Covenant, will appeare, and bring in a verdict for us, of not Guilty of Malignancy, Apostacy, or State Enmity … “.

Thus, many felt that the oaths that they had previously sworn (including The Solemn Oath and Covenant, 1643) conflicted with the Engagement, but such oaths also attested to their loyalty to country and Parliament [2, 3]. Amongst those who refused to sign was the Rev. Robert Constantine, minister of Oldham parish church; as a result, he was removed from his parish.

The Engagement was poorly subscribed and enforced, and the minutes of the Manchester Classis [5] (Presbyterian meeting of local ministers and church elders) show that Constantine was present at the meetings of the Classis up to the 8th October 1650. However, no minister or elders from Oldham are in attendance at the next meeting on the 12th November. Indeed, it wasn’t until five months later that elders from Oldham appeared at the Classis meeting but still no minister; the minutes showing a point of order “… that a summons bee sent to Mr. Lake to appeare the next classis.”. And, the summons reading: “The classe, takeinge notice of your officiateinge at Ouldham without theire approbacion, and not haveinge received satisfaction that you are a lawfull ordayned minister, doe desire and expecte your appearance at the next classical meeteinge the second Tuesday in April next.”.

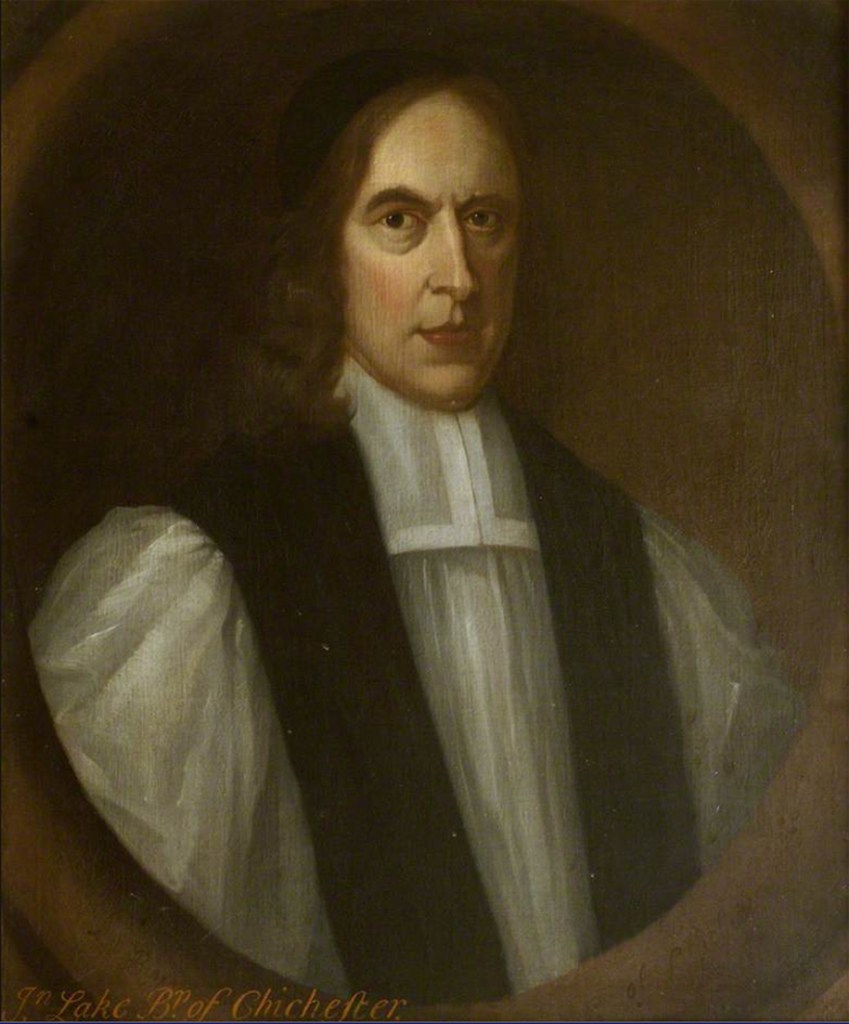

The Rev. John Lake was the man who had taken Constantine’s place in Oldham parish, and who would be at the centre of much debate both in the Classis and in his parish over the next four years.

Presbyterianism versus Episcopalianism

In many ways this pair of ministers, and the battle fought over the parish of Oldham, encapsulate the struggle over the structure of the British church that took place in the years of the Civil War. This tussle had three main factions in the Church of England: the Independents (of which Cromwell and the New Model Army were exponents), the Presbyterians (e.g., Robert Constantine) and the Episcopalians (e.g., John Lake).

The Independents espoused ‘toleration’ in religion allowing all to practice their faith in their own way. On the other hand the other two factions were very different in their approaches to religious worship. The main, obvious difference was the governance of the church. The Episcopalians supported an hierarchical structure that included bishops. On the other hand, Presbyterians favoured a system in which decisions were made by a committee of ‘elders’ chosen by the congregation and in which a regional Presbytery (or Classis), consisting of elders and ministers, developed and enforced an overarching theology. It was the differences in theology which brought about variance in religious practice that caused most disagreement, and disgruntlement, in congregations.

In many ways the religious struggles during the Civil War period have their roots in the Elizabethan Settlement of 1559. There were many who felt that the English Reformation was incomplete – removing papal governance, but retaining the episcopal hierarchy and some of the ritual ceremony of the Catholic church. As a result in the years between the reign of Elizabeth and the accession of Charles I, religious practice slowly evolved to become more Calvinistic or Puritan. However when Charles came to the throne (1625) one of his most trusted advisors was William Laud, the Bishop of St David’s. Laud was quickly promoted to Bishop of Bath & Wells (1626) then to Archbishop of Canterbury (1633). One reason Laud was so favoured by Charles was his espousal of the theory of the Divine Right of Kings (the idea that the monarch is only answerable to God, not his subjects or Parliament). Indeed, Laud was a fervent supporter of Charles’ Personal Rule – period from 1629 to 1640 in which Charles reigned without once calling Parliament.

Using his position as the religious leader of the Church of England, Laud proposed a series of changes that removed many Puritan practices and aimed to return the church to its state following the Elizabethan Settlement. The changes included a rejection of the communion table, reinstituting the high altar at the east end of the church, the enforced use of his own modified Book of Common Prayer, and an attempt to restore pre-Reformation church iconography and clerical vestments. To the Presbyterians, all these changes smacked of Catholicism.

Despite Puritan opposition, Charles believed that there should be uniform worship across his kingdoms, and as such he tried to impose Laud’s changes on his most fervent Presbyterian subjects – the Scottish Kirk. In response, the Scottish ministers came together and created a document in defence of their beliefs and a rejection of Laud’s innovations called The National Covenant. The confrontation between the Scots and Charles would ultimately lead to the Bishops’ Wars (1639) which Charles would lose, and together with an Irish rebellion (1641) and disputes with Parliament over taxation (e.g., ‘ship money’), would eventually result in the First English Civil War (1642).

A temporary victory for Prebyterianism

During the First Civil War, Archbishop Laud was charged with treason by Parliament and ultimately executed in January 1645. The same month saw Parliament pass an ordinance setting out a strictly Presbyterian form of religious observance: A Directory for the Public Worship of God throughout the Three Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland [6]. The Directory replaced Laud’s Book of Common Prayer, and saw the introduction of new, Puritan forms of religious observance, in particular the Presbyterian policies of replacing the high altar with a centrally-located communion table, restricting communion to only those approved by the elders, and the removal of some of the rituals associated with baptism (e.g., sign of the cross) [6]. The changes also extended to a complete overhaul of church governance – replacing the Episcopal hierarchy with Presbyterian Classes. Bishops were abolished in 1646, nevertheless the Presbyterian system of Classes and the acceptance of the Directory struggled to take hold, even in very Presbyterian places such as Lancashire [6]. As a result, parishes were led by ministers of a variety of persuasions leading to clashes between the ministers and their congregations, between the ministers and their Classes, and disputes over the appointment of those ministers (e.g., Oldham Parish – Constantine vs. Lake) [7].

As alluded to previously, the dispute over the ministry of the parish of Oldham is an example in miniature of the clash between the Scottish Presbyterian church and Archbishop Laud. Robert Constantine was a Presbyterian member of the Manchester Classis, and was actually in the process of matriculation from the University of Glasgow (May 1638) [8] at the time of the signing of The National Covenant. In contrast Constantine’s nemesis, John Lake, was an ardent Episcopalian who volunteered for service with Charles I in Oxford and was a Cavalier participant in the defence of Basing House and Wallingford [9].

Constantine, Lake, and the Engagement

Robert Constantine first obtained the Cure of Oldham parish in November 1647 [10], and he appears to have been well accepted by the congregation and a conscientious attendant of the Manchester Classis for the next three years [5]. The saga of the dispute over his ministry began with his refusal of the Engagement in 1650. According to John Vicars [11], Constantine’s removal from the parish was instigated by “One Mr. Midgeley a Schoolmaster in Ouldham…” and enforced by a local Justice of the Peace, James Ashton Esq. of Chadderton. Indeed, in an entry in the Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series (1650) [12] there is a note: “To Write Jas. Asheton of Chadderton, to send for Robt. Constantine, late preacher at Oldham, and examine him on depositions taken concerning his seditious preaching against Government,…“. Vicars describes Ashton as a ‘malignant’ (i.e., a Royalist) in the First Civil War, but one who later would sign the Engagement “… and turned a great stickler …”. Indeed, Ashton attended 100% of the Quarter Sessions whilst in office and witnessed the Engagement oath three times [3]; his zealotry perhaps, only cut short by his sudden death less than six months after Constantine’s ejection from the parish.

In point of fact it was James’s father, Edmund Ashton, who had been a Royalist, taken into custody in Oxford by General Fairfax at the end of the First Civil War. He was charged with ‘delinquency’ due to him “… deserting his dwelling, living in the enemy’s quarters assisting those forces against Parliament.”, and had his estate sequestered by Parliament [13]. Indeed, the sequestration of the Ashton family estate might provide another explanation of James Ashton’s fervour in prosecuting Constantine. Ultimately, the Ashtons compounded for their estate (bought back) at a cost of £1414 (about £150,000 in today’s money), and amongst the stipulations of the compounding was that they give up the tithes from the Chapelries of Oldham and Shaw. Of course, the eventual beneficiary of these tithes would be Robert Constantine [14].

Despite also refusing the Engagement [9], the Rev. John Lake had been accepted as a preacher in the nearby parish of Prestwich in early 1650. The Manchester Classis minutes of 12th February note that “A summons to bee drawne up to require Mr. John Leake [Lake ], the preacher at Prestwich , to attend the next classicall meeteinge at Manchester, …” [5]. Lake was also asked to submit a testimonial to attest to the ‘… soundness of his doctrine …”; however, this document never appeared. The next we hear of him is in the following year, when he was again summoned to the Classis, this time for officiating at Oldham without their approval (March 1651) [5]. Again Lake appeared recalcitrant. He attended the Classis in April, but refused to follow the guidance of the Classis on provision of the Lord’s supper. Presbyterian policy was for only those designated by the elders as fit to receive communion to do so. Lake had apparently ignored the advice of the elders of Oldham, and “… declared [his] resolucon is to administer the supper of the Lord … by [his] solitarie power …“. Lake didn’t appear at the next meeting, and two more letters were sent: one, to him concerning his dispensation of communion, and another to the elders to provide witnesses as to Lake’s behaviour.

In June two men from Oldham appeared at the Classis meeting. Caleb Broadbent testified that on two Sundays in April, the communion table had been prepared for the Lord’s supper, and that Mr. Lake had informed the congregation that only those who were strangers to the parish should desist from receiving communion. John Worrall testified that, on another occasion, Mr. Lake had announced that only the very young and those that had not already received communion should exempt themselves from the supper. After these testimonies, no further mention is made of Oldham’s minister or elders in the Classis minutes until January 1653 when a point of order states that “… notice bee given to some of the elders of Ouldham to bee present at the next classis in reference to Master Lak’s busines …” [5]. Finally in August, two elders from Oldham appear at the monthly Classis, but no minister. Elders appear intermittently over the next several months, but no minister until March 1654, when Robert Constantine returns.

Henry Wrigley, Constantine’s champion

The main protagonist involved in bringing about Constantine’s restoration to the parish was a man named Henry Wrigley. He is variously described as a linen-webster, chapman or draper, and was one of the first dealers in cotton and ‘fustian’ cloth in Lancashire (see Wadsworth & De Lacy Mann [15]). He was originally from Salford, but purchased Chamber Hall (see Fig. 3) in Werneth within Oldham in 1646 [16, 17]. Wrigley was described as a man of ‘pious and religious carriage’ [18] whose Presbyterianism is attested to by his numerous appearances at the Manchester Classis and Provincial Synods between 1649 and 1658 [5]. The concurrence of his religious beliefs with those of Constantine probably explain his motives in support of the ejected minister. In addition, his purchase of Chamber Hall came with “… All those the Manners and Lordshipps of Werneth and Ouldham …”. As lord of the manor he would have wielded much power in the area, including the ability to force the return of Constantine to the parish.

Wrigley’s ascendancy to this lordship is a reflection of the rise of the ‘merchant class’ in the late-Tudor/early-Jacobean era. Chamber Hall had been in the possession of a landed-gentry family, the Tetlows, for several centuries [19], but was now owned by a commoner. His great success was due in no small part to the fact that he had seen a gap in the market for cloths made from cotton. Cotton clothing was highly-fashionable but was imported and expensive; however Wrigley, and several other Manchester traders, realized that local handloom weavers could work with ‘cotton woole’ just as easily as with linen or sheeps’ wool (for discussion, see Wadsworth & De Lacy Mann [15]). In the early 17th century cotton woole had begun to be imported into London from the Levant (the Eastern Mediterranean). As a result, Wrigley set up a business in London to buy cotton and transport it to handloom weavers in south-east Lancashire for the manufacture of coarse cotton cloths such as fustians – a mixture of cotton and linen. By 1626 Wrigley was already highly active in the trade [15] and in 1635 so well-established in the capital that he was made a freeman of the City of London [20]. His partner, who appeared to take care of much of the business in London, was a Joseph Hunton, a salter (or dye merchant), who would also later be made a freeman of the City [21]. Correspondence between the two, reveals Hunton dealing with numerous shipments of goods for Wrigley to various parts of England [22]. Another document shows Hunton dealing with a London property rented out by Wrigley to another salter called Alexander Poore [23]. Interestingly, this tenement in Bartholomew Close is next door to the largest Cloth Fair in the country, St Bartholomew’s Fair, which had grown to international importance by 1641 (see Fig. 4).

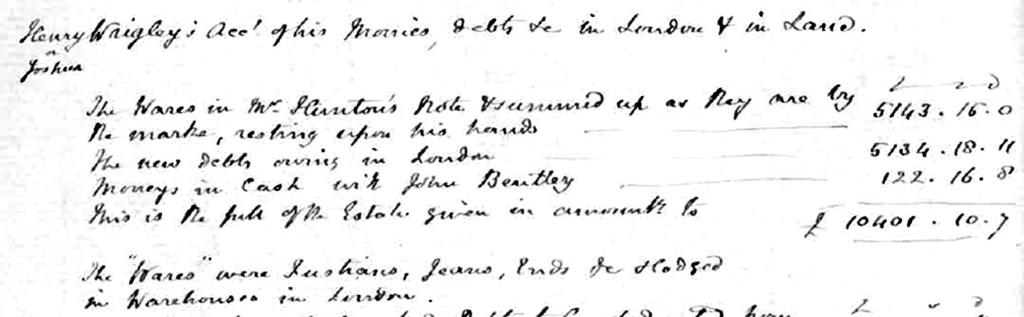

Having a representative in town, and owning property in London would clearly be beneficial to his business. Indeed, accounts provided by Hunton to the Committee for Sequestration (c. 1644) [24] show his holdings in London amounted to over £10,000, much in merchandise such as fustians in his warehouses (see Fig. 5). The inventory also lists a number of debtors; including all the debts owed to him gives a total estate value of £15,575 (approx. £1.7 million in today’s money). A few years later, Wrigley would use this wealth to buy Chamber Hall in Werneth (£2,050 in 1646), and later the Langley estate in Middleton (£1,998 in 1650) [24, 25]. When he died in 1658, Wrigley left Chamber and all his lands in Oldham to his youngest son, Benjamin [26]. It would appear that his middle son, Henry, was already in possession of the Langley estate, and the two properties would remain in the family for several subsequent generations [19, 27]. Still, the fact that the accounts shown in Fig. 5 were presented to the Committee for Sequestration reveal that things were not always plain sailing for Mr. Wrigley.

Wrigley’s run-in with the law

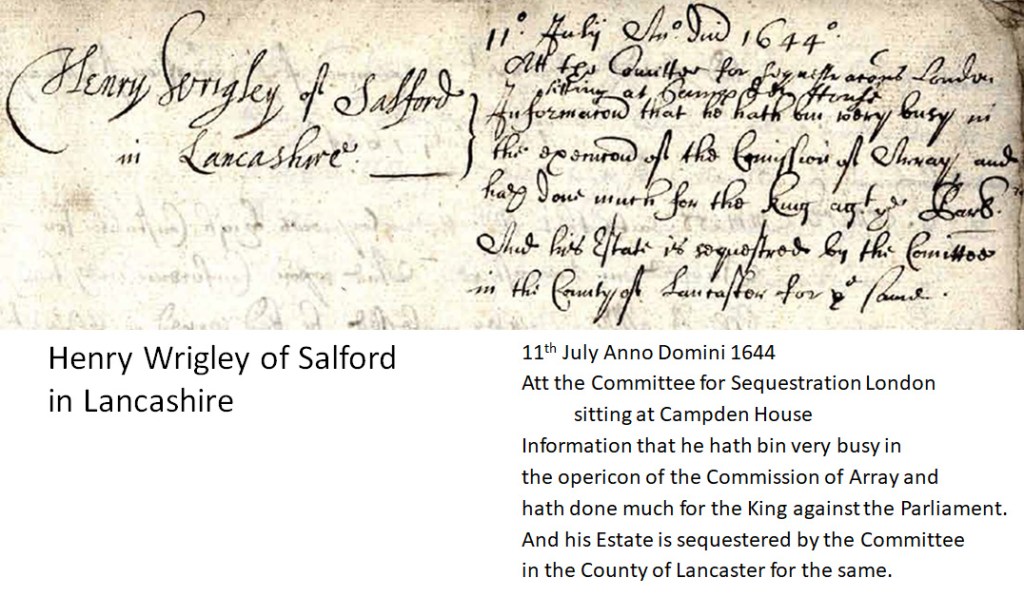

When he signed The 1641 Protestation in Salford (an oath of allegiance to the Crown), Henry Wrigley was described as the borough Reeve of the town [18], also later becoming the High Constable of the Salford Hundred [24]. However, it appears that his behaviour around the time of the siege of Manchester (1642) had come under the scrutiny of Parliament. Transcripts made by the Rev. Francis Raines [24] of the charges against Wrigley, and recounted by John Bailey [18], seem to show that at the time of the siege he was caught between a rock and a hard place. As a Crown-appointed official he was obliged to obey the Commission of Array and muster men to fight on behalf of the King; however, many of his neighbours in south-east Lancashire had sided with Parliament. It seems he fulfilled an initial request of the Commission, but then decided not to be involved in further musters and fled to London. In his defence, a letter was sent by four local ministers to the Lancashire MPs in Parliament testifying that Wrigley was not a malignant [24]. Ultimately in the summer of the following year, his case was brought before the Committee for Sequestration (see Fig. 6).

The committee deposed seven witnesses [28]. Of these, three men stated that they had ‘heard’ that Wrigley had served a warrant under the Commission of Array to muster men on behalf of the King; so, apparently hearsay evidence. The other four witnesses had more direct evidence that Wrigley had received and enacted such a warrant, but one of them admitted that Wrigley had only served this warrant after asking Colonel Ralph Assheton (Parliamentarian general) for protection if he refused to serve the warrant. Apparently, Assheton declined to promise Wrigley sanctuary; and so by his own admission [28], Wrigley went ahead and served the warrant. Nevertheless, one of the witnesses also conceded that Wrigley deliberately removed to London to avoid having to execute further warrants.

About two weeks later a certificate was provided by the Committee for the Counties Palatyne of Lancaster and Chester to the Committee for Sequestration signed by 39 notable citizens of Manchester and the surrounding area [24]. The letter included this statement on Wrigley’s behalf: “That at the tyme of that Siege the said Mr. Wrigley (being at London) voluntarily of his own charges brought there two brasse pieces [canons] for the use of the Towne of Manchester to be imployed in this present Service And besides his subscriptions of Money uppon the proposalls of Parliament did lend the sum of £100 to Sir Thomas Fairfax [Commander of the New Model Army] att his last being att Manchester for the advancement of the Cause That willingly traynd there, Men and Armes, and being himself trusted hath (with other well affected Townsmen of his ranke & quality) appeared in armes in his own person for the Countenance of the Service and hath payd & borne all Taxes taxacions & Contribucions for the fortifying of the Towne of Salford & all other publick Services, as hee hath beene from tyme to tyme required according to his proporcion.”

It seems that the testimony of his fellow citizens and his own evidence were sufficient for his release, and the restitution of his estates. As mentioned above, he would use his wealth to purchase extensive properties around Oldham, and would move there in 1646.

Lord of the Manor

Despite purchasing the lordship of the manor, Wrigley wasn’t appointed as an elder of Oldham parish until 1649. Indeed, according to the Classis minutes, there was much trouble in appointing elders to Oldham parish church at this time. The minutes note that in May 1648 the ”… congregation desire that they might not bee pressed to set up the govermtt at present because of some obstruccions …” [5]. The struggles to appoint elders in Oldham continued on through December “… parishioners at Ouldham were appointed to produce witnesses to prove theire exceptions against the election of elders …”. It wasn’t until seven months later that the newly-elected elders appeared at the August meeting of the Classe with Henry Wrigley being one of them [5].

Technically, there was no ‘manor’ of Oldham, but historically Werneth Hall home of the Cudworth family, lords of the manor of Werneth, has always been considered the principal manor in the town. This fact seems to have been based on the fact that it was originally the seat of the Oldham family [29] and that the Cudworths were related to the Oldhams by marriage [30]. However the Tetlow family, who owned Chamber, were also related by marriage to the Oldhams [30] and, as stated above, the sale documents of Chamber Hall seemingly give the new owner lordship of the manor of Werneth and Oldham (Note: The Indenture of the previous sale of Chamber Hall by Robert Tetlow to the Wood brothers in 1635 also includes the statement “… To have and to holde … the said Manors & or Lordships of Werneth and Oldham …”; LRO – DDHP/20/31). Mawdesley also describes a dispute between the lord of the manor of Werneth, John Cudworth, and Henry Wrigley over a chapel in Oldham church [31]. Clearly, there may have been much animosity between the lords of the two manors (Chamber and Werneth). The Cudworths had never attended the Manchester Classis as elders of Oldham church, so were most likely Episcopalians. Together with the wrangles over the chapel and the arguments about the predominance of one manor over another, it’s possible that the ‘obstruccions’ and ‘exceptions against the election of elders’ reported in the Classis’ minutes were brought by the Cudworths and other Episcopalians in the congregation.

Considering Wrigley’s eventual appointment as an elder, the choice of John Lake as a replacement for Robert Constantine as the minister for Oldham parish is something of a mystery. Wrigley may have been powerless to prevent the Constantine’s ejection from the parish, but why didn’t he stop the installation of Lake? Just prior to his move into the Cure of Oldham, Lake had been preaching in the parish of Prestwich which, historically, was the mother church of the chapel-at-ease at Oldham. It seems some of the congregation in Oldham invited Lake as a ‘suplyer’ for Constantine while the incumbent was ‘on tryal’, but that he promised to leave if Constantine was allowed to return. In the event, Constantine was ejected and Lake remained in place. One can only speculate that a significant number of parishioners, including the Cudworths, were theologically Episcopalian and Wrigley may have found it very difficult to remove the new minister – especially when Lake proved to be very capable of ignoring the pronouncements of the Classis. As the old saying goes: possession is nine-tenths of the law!

Constantine’s restoration

Following Constantine’s ejection in 1650 there was sporadic attendance of Oldham elders at the Manchester Classis, but never the minister. The first evidence of an attempt to remove Lake appears to come from outside the parish in a letter of August 1652 [28] to Col. Charles Worsley (later to be Manchester’s first MP) from Henry Root, a minister in Sowerby in Yorkshire. It’s not clear why the letter was sent; although, the wording seems to imply that Root had been approached by Oldham parishioners to act on their behalf. However, at this time Robert Constantine was resident in Birstall not 15 miles from Sowerby – did Constantine seek Root’s help in restoring him to his living? Root’s charges were based on his knowledge of John Lake when both were preaching in Halifax around 1647 [9]. In his letter he accused Lake of being an enemy to Parliament and having “ …kept company with the basest and most malignant.”. As a result, letters were sent to Lake by the local representatives of the Committee for Plundered Ministers demanding his attendance before them to answer questions [10, 28]. A series of seven charges were levelled against Lake which included that he had been a ‘grand cavaleire in former tymes’, that he was an ‘enemy to reformacon’, that he administered the sacrament in a ‘general and promiscuous’ way, and that he ‘doth baptyse basthardes’. A witness to the committee, a Mr. Rigby, said that he had heard that, before coming to Oldham, Lake had been a cavalier and had kept the company of ‘malignants’. He also confirmed that Lake, ‘by his own words’, was an enemy of reformation, and had indeed administered the sacrament to ‘severall cavaliers and disaffected persons … from remote parts’.

Along with these proceedings, the Raines manuscripts [24] and Classis minutes [7] also show letters from the Rev. Lake between November 1652 and January 1653 defending his behaviour to Henry Wrigley. Lake never denies the accusations about his religious practices, and argues that anyone with a clear conscience should be able to partake in holy communion, and that the newborn shouldn’t be condemned by the sins of the father. He is clearly an erudite man, but he knows it, and comes across as somewhat pompous – treating Wrigley like an upstart, uneducated tradesman. In one letter, Lake alludes to ‘underhand actings, which are against me’, and accuses Wrigley of disingenuousness – ‘not sought … with that sincerity on your hands … as it was intended on my hand’. And in another he says: ‘As to your pretended desires that there may be fair and plaine dealing …’. Unfortunately Wrigley’s correspondence has not survived, but clearly there was no love lost between the two men.

Following this flurry of correspondence there was a lull in the moves to remove Lake from the parish. It’s not until July of the following year that a document is drawn up that sets out the conditions for the departure of John Lake and his replacement by Robert Constantine [28]. The contract was between John Lake and John Milner on one part and Robert Constantine and Henry Wrigley on the other part. It states that on the 25th December 1654, John Lake agrees to “ …quietly and peaceably resign upp to the said Robert Constantine the rectory of Oldham, with all the profits thereunto belonging… “. Nevertheless, he still dragged his feet, refusing to sign the original document because of a disagreement over the wording. Eventually, the parties came to an arrangement and Lake finally resigned on the 30th December. In March 1655 Constantine appeared at the Manchester Classis meeting, and on the 12th April the trustees of the parish issued a certificate confirming his appointment [14].

The aftermath

Henry Wrigley died just four years after his victory in reinstating Constantine. He was clearly a key figure in establishing the manufacture of cotton cloths in southeast Lancashire. In his lifetime, he was the Borough Reeve of Salford, the High Constable of Salford Hundred, he was made a freeman of the City of London, and in 1651 he served as the High Sheriff of Lancashire. Wrigley’s family remained wealthy landowners in the area around Oldham for nearly a hundred years, one of his great grandsons, another Henry, even serving as a rector in an Anglican church (Cockfield, Suffolk; 1743-1767) [32, 33].

Constantine remained vicar of Oldham parish until the Act of Uniformity forced him out of his living once again. Ten years later, following Charles II’s Royal Declaration of Indulgence (1672), Constantine would find the freedom to begin preaching again, but it wouldn’t be until the Act of Toleration (1689) that he could found his own church, Greenacres Independent Chapel – the church where some of my ancestors were baptized and buried. Interestingly, the church that he founded was ‘Independent’ rather than Presbyterian, and it is now a Congregational church. In 1652, a letter from Henry Root had initiated the move to reinstate Constantine to Oldham parish. Root would later found the first Congregational church in Sowerby just across the County line. The fact that both men became Congregationalists again suggests that the men knew each other when they were both resident in the West Riding, and that Constantine may have recruited Root as an ally in his battle to regain his living in Oldham.

In contrast to Constantine, John Lake would rise to be a bishop, firstly of Sodor and Man, later of Bristol and lastly of Chichester. Nevertheless, he would once again find himself in the middle of a theological dispute. In response to James II’s Declaration of Indulgence (1687-88) Lake, and six other bishops, refused to have the Declaration read in their churches [9, 31]. These so-called Seven Bishops were arrested for seditious libel and imprisoned in the Tower. They were tried in the Court of King’s Bench, but found not guilty and eventually freed [9].

Conclusions

In many ways, the fates of these two vicars parallels the development of religious observance in England during the Civil War period, and its outcome at the end of the Republic: A temporary victory for Presbyterianism and Constantine during the Republic, followed by the Restoration and the restitution of Episcopalianism, the return of bishops (including John Lake), and the outlawing of non-conformism (at least temporarily) with the ejection of Robert Constantine.

Abbreviations: BHO – British History Online; CCed – Clergy of the Church of England database; COS – Council of State; LRO – Lancashire Record Office; PRO – Public Record Office; TLA – The London Archives; TNA – The National Archives

Bibliography:

1.^ MIDDLETON, J., Oldham, past and present. 1903, Rochdale, UK: Edwards & Bryning Ltd.

2.^ BURGESS, G., Usurpation, obligation and obedience in the thought of the Engagement controversy. The Historical Journal, 1986. 29(3): pp. 515-536.

3.^ CRAVEN, A., ‘For the better uniting of this nation’: the 1649 Oath of Engagement and the people of Lancashire. Historical Research, 2008. 83(219): pp. 83-101.

4.^ GEE, E., A plea for non-scribers. Or, The grounds and reasons of many ministers in Cheshire, Lancashire and the parts adjoyning for their refusall of the late engagement modestly propounded, either for receiving of satisfaction (which they much desire) or of indemnitie, till satisfaction bee laid before them, (which they cannot but expect.). 1650, London. 70 (Appendix: 66).

5.^ SHAW, W.A., Minutes of the Manchester Presbyterian classis (1646-1660). Vol. 2. 1891, Manchester, UK: The Chetham Society.

6.^ CRAVEN, A., ‘Contrarie to the Directorie’: Presbyterians and People in Lancashire, 1646–53. Studies in Church History, 2007. 43: pp. 331-341.

7.^ SHAW, W.A., Minutes of the Manchester Presbyterian classis (1646-1660). Vol. 3. 1891, Manchester, UK: The Chetham Society.

8.^ GLASGOW, U., Munimenta Alme Universitatis Glasguensis. Vol. III: p. 92. 1854, Glasgow: University of Glasgow.

9.^ STRICKLAND, A., The lives of the Seven Bishops committed to the Tower in 1688. 1866, London, UK: Bell and Daldy.

10.^ SHAW, W.A., Minutes of the Manchester Presbyterian classis (1646-1660). Vol. 1. 1891, Manchester, UK: The Chetham Society.

11.^ VICARS, J., Dagon demolished. 1660, Thomas Mabb: London, UK. pp. 7-8.

12.^ COS, Calendar of State Papers Domestic. 1650. p. 442.

13.^ PRO, The Royalist composition papers: Being the proceedings of the Committee for Compounding, A.D. 1643-1660 so far as they relate to the County of Lancaster, ed. J.H. STANNING. Vol. XXIV. 1891, Manchester, UK: The Record Society.

14.^ LRO, DDHP/20/62: Certificate by trustees; Robert Constantine as minister of Oldham. 1654, LRO: Preston, UK.

15.^ WADSWORTH, A.P., & De LACY MANN, J., The cotton trade and industrial Lancashire 1600-1780. 1931, Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

16.^ LRO, DDHP/20/46: Conveyance of Chamber Hall. 1646, LRO: Preston, UK.

17.^ LRO, DDHP/20/47: Bargain and sale of Chamber Hall. 1646, LRO: Preston, UK.

18.^ BAILEY, J.E., The Protestators of Salford, Kersal, Broughton, and Tetlow, 28 Feb., 1641-2. Palatine Note-Book, 1884(July): pp. 100-111.

19.^ BUTTERWORTH, E., Historical sketches of Oldham with an appendix containing the history of the town to the present. 1856, Oldham, UK: John Hirst.

20.^ LRO, DDHP/39/26: Grant of freedom of London to Henry Wrigley. 1635, LRO: Preston, UK.

21.^ TLA, Hunton: Freedom of the City of London, in Corporation of London. 1645-1647, The London Archives: London, UK.

22.^ LRO, DDHP/39/13: Letter concerning shipments of goods. 1650, LRO: Preston, UK.

23.^ TLA, Property deed – Bartholomew Close, in Miscellaneous deeds. 1644, The London Archives: London, UK.

24.^ RAINES, F.R., Lancashire Manuscripts: Volume 37B, C.s. Library, Editor. 19th Century: Manchester, UK. p. 360-386.

25.^ LRO, DDHP/17/14: Lease of Langley estate for peppercorn rent. 1650, LRO: Preston, UK.

26.^ TNA, PROB 11/289/332: Will of Henry Wrigley of Oldham, Lancashire. 1658, The National Archives: London, UK.

27. BHO, Townships: Middleton, in A History of the County of Lancaster, W.B. FARRER, J., Editor. 1911, BHO: London. pp. 161-169.

28.^ RAINES, F.R., Lancashire manuscripts: Vol. 32, C.s. Library, Editor. 19th Century: Manchester, UK. pp. 19-40.

29.^ BHO, The parish of Prestwich with Oldham: Oldham, in A history of the County of Lancaster, W.B. FARRER, J., Editor. 1911, BHO: London. pp. 92-108.

30.^ BUTTERWORTH, J., The History of Oldham with a plan of the town, directory, &c. 1817, Oldham, UK: J. Clarke.

31.^ MAWDESLEY, J., Presbytrianism, royalism and ministry in 1650s Lancashire: John Lake as minister at Oldham, c. 1650-1654. Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society (Vol. 108, pp. 136-59), 2015. White Rose Research Online: pp. 1-36.

32.^ RAINES, F.R., Lancashire manuscripts: Vol. 8, C.s. Library, Editor. 19th Century: Manchester, UK. p. 361.

33.^ PROJECT, C. CCEd: Clergy of the Church of England Database. 2013; Available from: https://theclergydatabase.org.uk/.

34. FINCHAM, K., & TAYLOR, S., Vital Statistics: Episcopal Ordination and Ordinands in England, 1646—60. The English Historical Review, 2011. 126(519): p. 319–344.